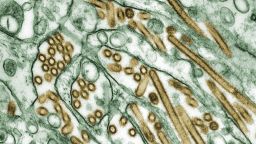

Bird flu is affecting a growing number of cattle herds in the US, and these infections?have led to only the second known human case in the nation, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There has been no human-to-human spread in the US, but there have been sporadic cases of people sharing the bird flu virus in other parts of the world, so the CDC says it is watching the situation closely. Like all viruses, H5N1 has the potential to mutate to become more of a threat to humans.

“The risk overall for the general public remains low,” Dr. Nirav D. Shah, the agency’s principal deputy director, said Wednesday. “But make no mistake, the CDC is activated as a result of these findings. We are taking this situation extremely, extremely seriously and are actively engaged in making sure that the public health response is robust.”

The risk is considered low, in part, because when humans have caught this version of the virus, it’s typically those who have close contact with sick animals. The infections usually stop there.

“So it may go from a bird or a chicken to a human, and that human may indeed pass it on to a spouse, for example, but what we don’t see thereafter is sustained transmission from human to human,” Shah said.

The latest case – in a person in Texas who had exposure to dairy cattle presumed to be infected – was mild, officials said, but humans can get severely ill and die from the disease.

“So even though we haven’t seen sustained transmission, we take this seriously, and that’s why the CDC has sprung into action,” Shah said.

Shah said the agency and its local public health partners have been watching out for anyone who may have interacted with these herds and may have bird flu symptoms. They are testing only people with potential symptoms because of a concern over false positives.

About 15 people have been tested in this outbreak, the CDC says, and only one had the virus.

The Texas patient’s only symptom was red eyes, and the CDC notes that it is not one typically associated with this flu, which more often causes a cough, fever or shortness of breath.

“In this respect, we want to be testing more people rather than fewer people, so that’s why we went ahead and greenlit the testing for anybody with symptoms who have been exposed,” Shah said.

Doctors treated the Texas patient with an antiviral medication commonly used for the more familiar flu virus, and the person went into isolation.

If the virus does mutate and spread among humans, the CDC said, it is prepared and can use existing products to detect and protect against it. The strain that was recovered from the latest person who was sick is the same version as in the sick cows and as has been circulating in birds.

“We have not seen any changes to the genome that would suggest a reduced effectiveness of either vaccines, [the antiviral drug] Tamiflu or diagnostic tests,” Shah said.

Scientists discovered the first cows sick with the virus in two dairies in Texas in March, the first cows known to be infected with bird flu. More humans may have been exposed to the virus since the US Department of Agriculture said Monday that it had detected the flu in a herd of dairy cows in New Mexico and five additional dairy herds in Texas. This was the first time the virus had been found in cows in New Mexico.

In total, seven herds have been affected by bird flu in Texas, two in Kansas, one in Michigan and one in New Mexico, the USDA said. It is also suspected in a herd in Idaho, but those test results are still being analyzed.

Since the start of this outbreak of bird flu in January 2022, more than 82 million poultry in 48 states have been affected, according to the CDC. Cases were also detected in 9,253 wild birds, although the true number is probably much higher.

The virus has shown up in relatively fewer mammals, although those numbers have also been growing. Baby goats, ducks, geese, deer, foxes, raccoons, opossums, skunks, pet cats and other animals have tested positive.

Watching the virus jump to cows has been a concern, said Dr.?Thomas?Inglesby, director of the?Johns Hopkins?Center for Health Security.

“It is important whenever there’s a change – and this is a change that cattle are infected for the first time that we know about, and this?is only the second human case in the US that’s been detected – every time there’s such a change, we need to dig into that and make sure there’s nothing more than just a single one-off case from industrial exposure,” he said.

Shah said people shouldn’t be alarmed by the official name for the virus: highly pathogenic avian influenza.

“That name, in and of itself, may raise the blood pressure of many people who are reading or watching. The ‘highly pathogenic’ part of the name refers to its virulence and severity in birds, not humans,” he said. “Indeed, if you are a migratory bird, this virus is bad news.”

Ducks and geese can carry the virus without appearing sick, but?poultry?aren’t always so lucky. Highly pathogenic avian influenza carries?“very high mortality rates”?among chickens and turkeys, and farmers are concerned because it has continued to spread despite their best efforts to contain it.

Because the virus spreads easily?and can kill birds quickly, farmers usually have to cull even uninfected birds to prevent a wider outbreak.

On Tuesday, Michigan reported cases in a commercial poultry facility. On Wednesday, the nation’s largest egg producer found bird flu in a Texas facility.

Cal-Maine Foods said it will have to depopulate 1.6 million laying hens and 337,000 pullets at its Texas facility, according to state Department of Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller, who called it “absolutely devastating news for Cal-Marine and the entire Panhandle region, which has already suffered so much already.”

People who work with sick birds have had to take precautions, Inglesby said, but everyone doesn’t have to get rid of their bird feeders. Studies have shown?that bird flu may spread to songbirds, but the ones that typically gather at feeders – such as cardinals, sparrows and blue birds – and those you may see on the street like pigeons and crows do not typically carry bird flu viruses that would be a threat to humans,?according to the CDC.

However, “it’s always a good idea to wash your hands when you’re interacting with wild birds,” Inglesby said.

With cows, the recommendation is that they be put into a special pen for sick animals?, and they typically recover in seven to 10 days.

Based on current knowledge, ranchers do not have to kill sick cows, Shah said. None of the cows in the sick herds have died from the infection as of Wednesday, he said.

The cows probably caught the virus when they encountered wild migratory birds; however, the USDA’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service said it couldn’t rule out cow-to-cow transmission, based on the spread of the illness among a herd in Michigan. The virus didn’t appear to have any kind of respiratory transmission but more likely spread through infected milk.

“That appears to be the leading theory at this point,” Inglesby said.

Although the virus can be found in high concentrations in milk from sick cows, it does not pose a threat to humans who drink milk or eat dairy products because most milk in the US is pasteurized and has to be so in order to be sold across state lines. The pasteurization process inactivates viruses before the product can go to market.

The US Food and Drug Administration continues to remind people that raw milk can pose a serious health risk to those who drink it.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

- Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“Before the situation at hand, CDC and FDA’s position was stay away from raw milk. Now what we’ve done is add an asterisk to that and said, ‘and we really mean it,’ ” Shah said.

Typically, the US has higher production of milk in the spring, the USDA said, and the infections in cows shouldn’t hurt the nation’s food supply. The agency says the milk lost from symptomatic cattle to date is “too limited” to have a major impact and shouldn’t impact the price of milk.

The USDA and the CDC said they will continue working with the industry and with local public health departments to monitor the situation and to encourage vets and farmers to report sick animals quickly so the impact of the virus can be limited.