For most South Asians, the phrase “What will people say?”?is all too familiar.

What will people say if you wear that revealing outfit? What will people say if you don’t pursue an advanced degree? What will people say if you marry someone outside of your religion? What will people say if you get a divorce?

You can swap in any hypothetical scenario that might spur societal judgment — the variations are endless.

Sahaj Kaur Kohli, a licensed therapist and founder of the online mental health community Brown Girl Therapy, knows the weight of that question well.

Born to parents with Indian and Sikh roots, Kohli was raised in a predominantly White suburb in Virginia and often found the collectivism of her immigrant parents’ culture at odds with the individualism of the West, she writes in her new book “But What Will People Say? Navigating Mental Health, Identity, Love, and Family Between Cultures.”

The differences between the two cultures became especially clear after a difficult period in college prompted Kohli to move back home.

When she told her parents she was battling depression and needed to see a therapist, Kohli says they worried how others might perceive her mental health struggles and tried to manage the situation on their own. It wasn’t that they weren’t concerned about her, Kohli adds — they were simply conditioned to think in terms of the family unit and community, believing their daughter’s depression could be seen as a failure on their part. But what will people say?

“We care so much about what other people will think that we forget about the people within the community or within the families who might be hurting,” Kohli said in an interview with CNN.

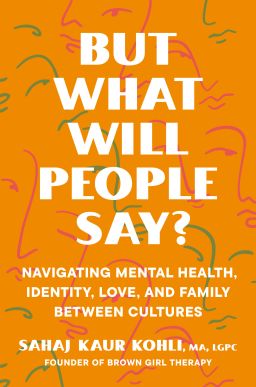

In “But What Will People Say?,” which published May 7, Kohli explores that fear of judgment, along with other challenges that children of immigrants commonly face: shame, self-sabotaging behaviors and the loss of cultural identity among them?.

Part memoir and part self-help, the book draws on Kohli’s personal experiences and her work as a therapist to help children of immigrants process their emotions, improve their family dynamics and develop a clearer sense of self.

Some of Kohli’s reflections and insights might resonate beyond her target audience. In the book, she opens up about her once-strained relationship with her father, the academic troubles she long kept secret and the trauma she endured — experiences that many people, children of immigrants or not, can relate to.

CNN spoke to Kohli about how to deal with guilt, how conversations around mental health in the West miss cultural nuance and how immigrant parents can better understand their children.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you want to write this book?

I wanted to write this book because I knew nothing like it existed. It’s something that I so desperately could have used growing up. I’m just so honored to be able to create something in a space that is predominantly White and individualistic by nature, and offer cultural nuance to the conversation of wellness.

Your book focuses on your experiences growing up in two cultures: the community-oriented Indian culture of your parents and the individualist culture of the West. What were the biggest tensions between the two?

That tension that I felt was every single day. I grew up with diametrically opposing values, norms and expectations. One of those cultural systems was the Western world. At home, I was being raised in a totally different environment that had different expectations of who I was supposed to be: as an Indian daughter, as an Indian woman, as a daughter of immigrants, as a South Asian woman.

I started to develop performative behaviors at school, around friends, around dating, around career, around how I showed up in those social environments and how I wanted to be perceived. I developed a second set of performative behaviors when I was at home, when I was going to Gurdwara (Sikh house of worship) on Sundays, when I was going to an Indian cultural event on the weekends or when I was talking to my parents.

The ways that we were taught to communicate, stand up for yourself or even start to learn about your own sense of self and your own needs is very different in the Western world than it is in the Eastern world.

I didn’t know it then but every single part of my life was at tension with one another based on how I thought I was supposed to behave to be accepted in the environments that I was living in.

When did you start to develop the language to process those feelings?

Very recently. Through working in media and working on identity-driven content and mental health content, I started to gain a language for wellness, identity and all of these things. But it wasn’t until I went to grad school in 2019, which was the same time that I started Brown Girl Therapy, that my whole world opened up.

It was through those experiences — building a community that didn’t really exist for a population that was underserved and learning Eurocentric techniques and tools in school that all catered to individualism — that I started to realize how important this work is and how much we need to infuse culture into these conversations.

What are some of the disconnects between Western therapy and the experiences of children of immigrants?

One of the biggest things is other-care. We talk so much about self-care and the individual to such an extent that it leaves out everything else. What children of immigrants, Asian families, non-Western communities and immigrant communities really center is family and relationships. We are being exposed to all of these ideas that revolve around setting boundaries, cutting people out and thinking about yourself first. How do we learn to stick up for ourselves while also being mindful of the cultural nuances in the families and the systems that we exist in?

So many of us feel as much pride and joy and rejuvenation from taking care of others and being in the roles that we play — whether it’s being a daughter, sister, parent — as we do as taking care of ourselves. That is something in the self-care narratives in the Western world that we don’t talk about enough.

There’s so much research on so many things that we just are not talking about: What’s “too close” in a family system? What is considered dysfunctional? What is considered codependency? What is considered enmeshment and not having any boundaries?

These things are very binary in the Western world, when in reality, it really does depend. There is this messy middle where things are neither good nor bad — they just are. How do we live in that messy middle? That’s the ethos to all of my work.

You share some very personal experiences in the book, like being sexually assaulted and taking a while to graduate from college — the kinds of experiences that children of immigrants are often taught to keep quiet. How did you get to a place where you felt comfortable being vulnerable??

The process of writing this book was so healing for me. I excavated so many old wounds, stories and my inner child by revisiting parts of my life and owning them for myself.

Even in writing about my college career, my editors had to push back a lot and say, “You still are not being very nice to yourself.” It was a process getting to a point where I was like, “Do I still feel shame about the fact that it took me 12 years to graduate college?” Sometimes. Sometimes I feel really embarrassed — that it means I’m not smart.

Then I have to remind myself that that’s not true. Life just happened in a certain way for me. I didn’t choose to struggle, and it doesn’t mean anything about me that it took me longer. Battling shame through self-compassion by writing this book is the ultimate form of liberation for myself.

We all have experiences that we feel so much shame for because we worry what other people are going to think about those experiences. If we just own them, we can dismantle that shame. And that’s what I did.

What are some of the most common issues that children of immigrants bring up in therapy??

Guilt.

The feeling of guilt. Navigating guilt. How guilt motivates us to not do the thing we want. How it motivates us to revert to behavior that might not be good for us. How guilt leads to shame. Guilt for having more access to resources and opportunities than our parents or our family abroad.

Guilt for being too American. Guilt for not being American enough. Guilt for not being enough of whatever our cultural identity is. Guilt for setting boundaries. Guilt for not setting boundaries. Guilt for picking the partner that we want to have. Guilt for choosing a different career path.

Guilt is the biggest thing I hear and see.

How do you advise people to work through that guilt?

Remember that guilt is an emotion like any other emotion.

So many of us will feel guilt and all of a sudden be like, “I’m doing something wrong. This is too uncomfortable. I need to stop doing the thing I’m doing.” In reality, guilt is just a yellow light. It’s a slow down sign. Guilt tells us we crossed a moral boundary. It’s very important to interrogate that. Is the guilt telling me that I hurt someone else? Is the guilt telling me I need to repair a relationship or repair something that I did that was wrong?

Oftentimes, the answer for children of immigrants is: Probably not. But what’s happening is that they are mistaking disappointing someone else for guilt that they are doing something wrong. If you come from two different cultures with different values, you’re going to feel guilt because you’re being fed conflicting definitions of what is good and what is right.

Do you feel guilt because your parents are subscribing to a different set of values that don’t align with yours? By choosing a different career, by choosing not to have kids or whatever, do you feel like you’re doing something wrong because they don’t believe in that? Or are you actually crossing your own values?

Really getting clear on your values and how it differs or overlaps with people you care about is important. Just because you feel bad doesn’t mean you’re doing something bad, and I think it’s really important for people to discern between those two experiences.

My biggest piece of advice is to really interrogate (the guilt) and to get clear on your values and whose values you’re crossing when you feel guilt. Then question whether you should change your behavior or if you need to learn to sit in the discomfort.

How do we work through these conflicts if our parents don’t have the same language and emotional capacity to deal with them?

I often hear, “I’m not the one who needs therapy. They need therapy.” Maybe they do, and maybe they’re not willing to take accountability. But that doesn’t mean that you don’t have agency over things that you can do differently.

If I were to learn, go to therapy and unpack more about how my relationship with my mom affects me, I might then start to learn tools to manage my emotions when I’m with my mom. Which means that when I’m with my mom, I might get less defensive, which means that our relationship dynamic automatically changes.

It’s important for people to realize that doing the work is never about changing other people, but it’s about changing the way you show up. (It’s about learning to) manage your expectations, decide what you are and aren’t willing to tolerate and how you can show up in that space within the relationship.

What’s your advice for immigrant parents who want to understand their children better?

Curiosity, connection and compassion are key.

Parent or not, it’s so easy to make assumptions about what someone else is feeling or thinking. It’s so easy to fill in the gaps in the story ourselves or to reinforce a story about someone else rather than actually ask or get more information. It’s really difficult to show up vulnerably in a relationship and say, “Hey, I’m learning too. I don’t know, but I want to hear more about what it’s like for you.”

If (the children) are really young and you’re still trying to figure out how to help raise them, then really embrace their bicultural identity. A strong and integrated bicultural identity is a protective factor against mental health issues. As a parent, you can embrace that. It doesn’t mean that you are allowing your kid to fully assimilate and forget where they come from, because I know that’s a very big fear.

I didn’t have this language growing up, but it’s very obvious to me now that my parents were scared. They were scared immigrants. They moved to a new country. They did the best they could. I loved them dearly, and because they were scared, all they did was want to retain a sense of control. So they tried to keep their kids close. They tried to make decisions for their kids. They tried to control how their kids acted or what choices they made. For a long time, that created a chasm between me and my parents. It was only in my late 20s that I was able to fill that chasm with them and build a new relationship.

To any parent, I would really encourage them to self-interrogate how they’re showing up and how their fears might be determining how they have a relationship with their kids or don’t have a relationship with their kids.