From his days as a clerical student, to overseeing executions as part of the judiciary, Ebrahim Raisi’s life has been intimately tied with Iran’s tumultuous modern history. Yet after all that, his presidency was notably unremarkable.

Unlike previous Iranian presidents, Raisi seemed content to serve as an empty vessel that carried out the reactionary policies of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei,?the final arbiter on policymaking. He showed none of the subtle pushback of his predecessor, the moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani. He also lacked the charisma of conservative former presidents who were happy to do Khamenei’s bidding?–?such as the firebrand Mahmoud Ahmadinejad?–?but who sought to carve out autonomy for the position of the presidency.

So, when foreign dignitaries from a whopping 68 countries gathered for Raisi’s funeral on Thursday, they may not have been preoccupied with thoughts of the late president.

This was not a game-changing death like the 2020 assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, the military mastermind credited with creating a strategic stranglehold over much of the Middle East and helping to put the US on the backfoot.

Raisi’s absence, in contrast, is unlikely to be felt. Yet his untimely death could hardly have come at a more pivotal time for Iran.

“Foreign dignitaries will be trying to get a read of the country,” Washington-based Iran analyst and executive vice president of the Quincy Institute Trita Parsi told CNN. “This is also an opportunity for many of them to manifest how their relationship with Iran has changed.”

Iran is deeply enmeshed in the war in Gaza, with Tehran-back armed groups engaged in a low rumbling tit for tat with Israel and its allies across four different countries. In April, it launched an unprecedented direct attack on Israel from its territory after an apparent Israeli airstrike on Tehran’s consulate in Damascus.

In this fraught moment for the region, leaders from Turkey to India and China – many of which declared days of national mourning for the late president – appear keen not to ruffle feathers. The deaths also come after years of diplomatic efforts to achieve a rapprochement with former regional nemeses, such as?Gulf powerhouses Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates,?both of which were represented at the funeral.

Qatar’s emir, as well the foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait attended the funeral. Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh, who the International Criminal Court is seeking an arrest warrant for alongside Israeli leaders, was also in attendance.

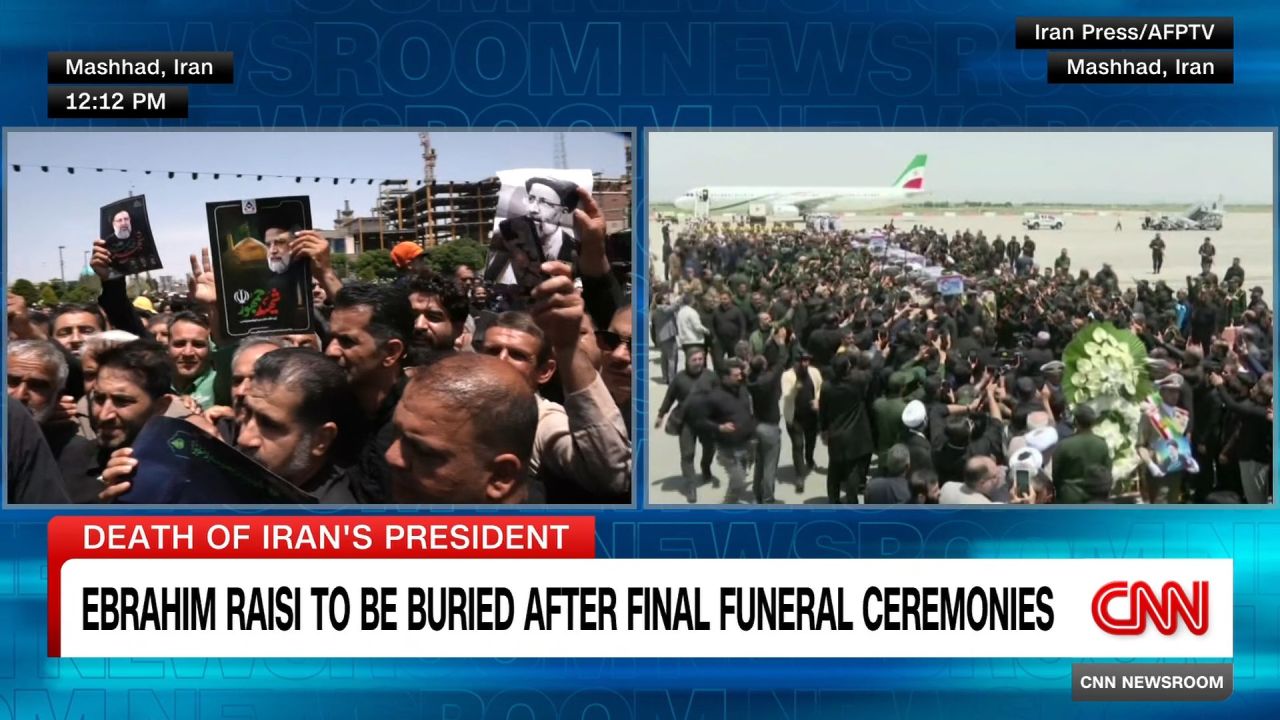

Tens of thousands flocked to the streets to mark the funeral, throwing flowers at the coffins. It was a strong show of support for the regime, and a demonstration of its powerbase. Iran’s populace is deeply polarized, but the regime showed that it could still mobilize a critical mass.

Iran today seems not to be the pariah state that former US President Donald Trump almost turned it into in 2018 when he pulled out of a landmark Obama-era nuclear deal that exchanged sanctions relief for curbs to Tehran’s nuclear program.

“This (funeral) is a way for countries to show the progress they have made in repairing relations with Iran,” said Parsi. “We have missed how Iran’s relations in the region have gone through a significant transformation.”

Foreign dignitaries are likely engaged in sideline chats to try to get a read on Khamenei’s opaque and sometimes unpredictable thinking on domestic policy?that could have repercussions for the region.

Constitutionally, a presidential election must be held within 50 days of the demise of a sitting president. That is a relatively short time to prepare for a race charged with consequence for Iran’s theocratic leadership. The election will have ramifications for the question of the succession plans of the ailing 85-year-old Khamenei, who is only the second Supreme Leader to rule the Islamic Republic. Moreover, the race can?either appease or, conversely, fuel the tensions brought on by?the?youth-led?nationwide uprising that rocked the country less than two years ago.

Khamenei has ultimate sway over elections through the country’s Guardian Council, which consists of jurists appointed by the Supreme Leader, and which is tasked with vetting election candidates. In the 2021 presidential election, the council disqualified most viable candidates besides Raisi, paving a clear path to his presidency. The race was widely seen as heavily engineered and produced a record low voter turnout.

The leader may orchestrate a repeat of that race. He could also decide to change tack, opening it up so that Iran’s next president enjoys broad popular support.

“The election can be a watershed moment for Iran,” Mohammad Ali Shabani, Iran analyst and editor of?Amwaj.media,?told CNN’s Becky Anderson. “(Khamenei) has a golden opportunity to reverse course in a face-saving way, make a U-turn, open up the space and allow people to run.”

During his tenure, Raisi made only feeble attempts to dispel the notion of him as a fig leaf president. He was widely criticized for presiding over the hollowing out of what remains of Iran’s institutions.

Legislative elections this March had a record low turnout of 41%.?The 2022 nationwide uprising posed the biggest domestic threat to the regime in decades. Since the brutal crushing of those protests, the bridge between the regime and its young and largely disgruntled population has grown ever wider.

“Khamenei has put the Islamic Republic on a path in which it will only be able to remain in power by increasing repression,” said Parsi.

Choosing to open up the election may appease the country’s frustrated young population buckling under continued economic and political strains. That may set Iran on a course to stabilize its restive domestic situation. It may also pave a path for a more Western-friendly administration like that of Rouhani, which presided over the landmark 2015 nuclear deal, albeit within the confines set by Khamenei.

Yet analysts say this remains wishful thinking.

“It’s difficult to see why Khamenei would change course at this point. It would necessitate that he recognizes that he is on a path that is not good for him, but that’s not the conclusion the regime has come to,” said Parsi.

“Because of the succession (of the Supreme Leadership), the regime wants the status quo. They’re going to choose a direction that keeps everything as-is.”