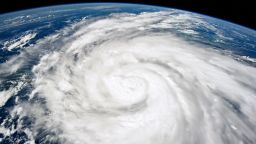

The official start of what is likely to be an active Atlantic hurricane season is almost here. While that introduces the threat of tropical trouble across the eastern US, the Gulf Coast states are at even higher risk to a hurricane’s deadliest threat: water.

Federal forecasters joined the?chorus of expert voices?calling for a hyperactive Atlantic hurricane season when NOAA’s National Hurricane Center released its official preseason forecast Thursday.

An above average season is expected with between 17 and 25 named storms. Of these storms, 8 to 13 could become hurricanes, 4 to 7 of which could strengthen into Category 3 or stronger. This is the most aggressive preseason forecast issued for NOAA’s hurricane season outlook.

“This season is looking to be an extraordinary one in a number of ways,” NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad said at the news conference.

The ominous forecast comes as a vast area of the South has been deluged by drenching, flooding storms in recent weeks and dozens of cities from Texas to the Florida Panhandle are having one of their wettest years to date.

The soil is saturated, and the more saturated it is, the less time it will take for heavy rain to trigger flooding, Barry Keim, a climatologist with Louisiana State University, explained. Soils in the South typically would be able to absorb a few inches of rain before becoming overwhelmed, but that’s not the case currently, Keim told CNN.

After weeks of rain, the ground is already overwhelmed.

Now the region is headed into its wettest season: summer. Tropical activity plays a vital role in making it so.

As much as 25% of annual rainfall for the Gulf Coast states comes from tropical systems, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. New Orleans, for example, typically receives between 15% and 20% of its 63 inches of annual rainfall from tropical systems.

But individual storms often unload much more than a few inches of rain – some of the most prolific have dumped feet of it, something becoming increasingly common as climate change supercharges rainfall in hurricanes.

And that’s a big deal with a potentially more active hurricane season and its increased chances for torrential, tropical rainfall on the horizon. Inland flooding surpassed storm surge as the deadliest threat from tropical systems, according to 2023 research from the National Hurricane Center.

Driven by a budding La Ni?a and extremely warm ocean waters, the National Hurricane Center and many other forecasters are calling for a hyperactive season starting June 1 that could place the US coastline at risk of more tropical strikes.

Drenching tropical systems could also arrive when they would do the most harm: early in the season. The region is often more vulnerable to flooding in the early part of hurricane season and that’s particularly the case this year, Keim explained.

A named tropical storm or hurricane has formed in either May or early June in every hurricane season since 2015. Not every storm threatened land, but some like 2022’s Tropical Storm Alex did.

This year’s exceptionally wet head start will likely extend the flood threat longer into hurricane season, unless summer heat ramps up quickly and bakes the moisture out of the ground. Last year, a dearth of tropical systems and surplus of heat domes suppressed rain and plunged parts of the South into the worst drought on record.

Latest hurricane outlook

There’s an 85% chance of an above average season and only a 5% chance the season will be below average, according to NOAA.

A waning El Ni?o and the anticipation of a building La Ni?a this summer is one of the biggest indicators that the upcoming season will be very active. El Ni?o tends to create more hostile upper level winds that rip storms apart while La Ni?a does the opposite.

Unlike last year, El Ni?o will not be around to curve many tropical cyclones away from the US, potentially leaving the coasts vulnerable this season.

Extreme, record-breaking ocean heat is another major factor an average season could be out of reach. Warm water acts like food for storms, helping them to form, strengthen and survive.

Off-the-charts ocean heat last year not only created more storms in the Atlantic by neutralizing the storm-dampening effects of El Ni?o, but also fueled explosive strengthening – called rapid intensification – of the storms that formed across the globe.

Rapid intensification is becoming more likely as the atmosphere and oceans warm in a changing climate.

And the Atlantic Ocean is still record warm, both at and below the surface.