Editor’s Note: Ali H. Elaydi is an orthopedic surgeon who practices in Texas. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. Read?more opinion?at CNN.

Ten months into the war in Gaza, there is just about nothing that the people struggling to survive there don’t need: water, food, shelter, security?— Gazans are literally blockaded from receiving the essential things of life.

They also desperately need skilled physicians like me. I’m an orthopedic surgeon. Earlier this year I completed my training at Yale medical school and I now work at a small practice in Texas.

Like many Americans, I have been eviscerated by images in the news of people who have lost limbs in the bombing by Israel or who were subject to crude amputation because an arm or leg was rendered useless after being crushed by falling masonry. As a physician, I felt compelled to help.

I was able to travel to Gaza in April, to help those wounded by Israeli bombardments that have killed and injured thousands who have become trapped in buildings, struck by shrapnel or hurt during missile strikes on refugee camps. After a rule recently imposed by Israel, however, I’m no longer allowed to lend my medical expertise to help in Gaza.

The medical mission I was part of, sponsored by an aid group called?‘FAJR’ Scientific, took place at the European Gaza hospital in Khan Younis, a facility that has since been evacuated. I planned to join a follow-up trip in June with the same aid organization and was to be placed at a hospital in central Gaza.

I got as far as Jordan when I learned that I had been denied permission to reenter by Israeli authorities. The reason, I’m told, is that I am Palestinian.

I was born in a refugee camp in Gaza four years into the?first Palestinian Intifada. At that time, Israeli forces had invaded Gaza. In those warlike conditions, violence was a normal part of our day-to-day life. We applied for political asylum in the US and were lucky enough to get it. I was five years old when we left. We were among the lucky few who were able to escape using that route. We fled?Gaza as refugees. Most of my extended family still lives in Gaza.

Through a long, winding process, I finally became a United States citizen when I was 18. I often felt guilty knowing that the loved ones I’d left behind would not benefit from the advantages that I got in the United States. I pursued a career path that would allow me to most impactfully give back to my homeland. Medicine was a natural choice, given my interests and aptitude.

In every application, in every personal statement, and in each interview, I expressed a career goal: to provide medical relief to those suffering in Gaza, to help those who couldn’t escape the ravages of war as I had.

In April, my orthopedic training at Yale was coming to an end, and the war in Gaza was raging. It almost seemed predestined that the conclusion of my long traineeship corresponded with the worst violence Gaza had seen. I knew it was time to make good on my promise and travel back to Gaza, to contribute my surgical skills, and to provide any assistance I could to a severely depleted healthcare system.

That two-week medical mission was a life-changing experience, as much for the volunteers as for the people we were fortunate enough to be able to help. There were 14 of us: 10 orthopedic surgeons, four anesthesiologists. We did a lot of good on that trip, but when it was time to return to the US, we were aware of how much work we still had left?to do. I signed up to take part in a monthlong followup mission in June.

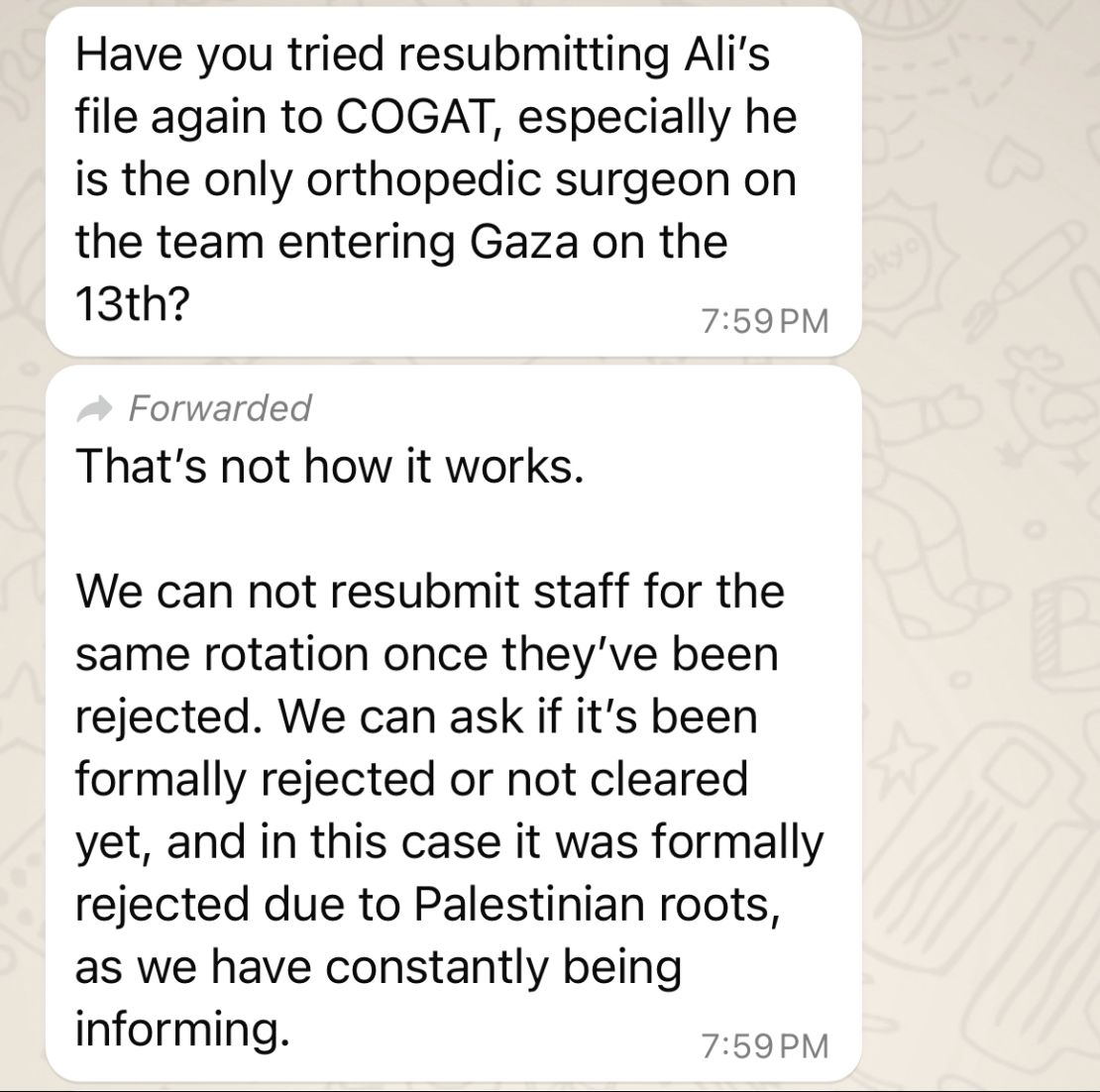

I had already received the necessary approvals from the United Nations and the World Health Organization. I arrived in Jordan several days before I and the other members of the medical team were to travel to Gaza. That’s when, just a few days before we were to depart, the organizers of the trip received a text saying that the Israeli authorities had approved everyone’s entry — but not mine. The message, which was forwarded to me, said that I had been?“formally rejected due to Palestinian roots.” Memories of my upbringing, my escape and my first mission to Gaza came flooding back to me, but with an intensified sense of helplessness. A tragedy, my own personal?Nakba, was unfolding. I could barely make sense of the words on my phone screen, so strong was my disbelief.

Misery and immense need of the kind I had seen in Gaza is why I went into medicine, and why I wanted to do orthopedic surgery. During that April mission, it was never far from my mind that I was one decision away from still being among the people suffering there. I was able to escape Gaza as a child but that doesn’t make my life any more valuable than the lives of people who live there. I didn’t want to be one of those people who just talked about helping those in need. My training was done.?This was my calling. This is why I went into medicine.

Israeli policy has made giving back impossible, however.

The policy decision exacerbates the already dire conditions in Gaza. The region’s health crisis is not an abstract statistic but a daily reality for millions of people.?Hospitals are overwhelmed, medical supplies are scarce and trained medical personnel are even harder to find. Every doctor, every nurse, every healthcare worker makes a palpable difference. I’ve borne witness to this fact.

That’s why refusing to allow doctors of certain backgrounds to volunteer cannot be considered simply a bureaucratic prerogative; it is a direct denial of health and well-being to the people of Gaza.

Israel’s policy excluding anyone with parents or grandparents who are Palestinian from being able to take part in humanitarian missions has meant that a lot of my friends who had signed up for upcoming missions were pulled from teams because of the same policy, whether they’ve ever previously set foot in Gaza or not.

I suspect that it’s just one of many tactics employed by the Israeli government to restrict the flow of aid to Gaza. On the first mission I was on, I was able to take 10 suitcases of medication with me. On the one I wasn’t allowed to take part in, we were allowed one bag and no medications other than those for personal use.

The international community must stand firm in condemning such practices and advocate for the sanctity of humanitarian assistance. The denial of a Palestinian doctor’s right to volunteer — in the process hindering the delivery of humanitarian efforts — is an affront. Governments around the world, international organizations and individuals of influence should do what they can to help reverse this inhumane policy.

Editor’s note: Abdullah Ghali assisted in writing this essay.