What did it mean to go viral at the height of the Renaissance? In Northern Belgium, which underwent a meteoric socioeconomic boom between the 15th and 18th centuries, it was through art, as a budding upper middle class in search of status symbols radically shifted how paintings were commissioned, and new mass-printing technology disseminated imagery far and wide.

As the region became a hub for capitalist and colonialist prosperity — including its significant role in the Spanish and Portuguese empires’ slave trade — the cities of Antwerp, Bruges and Ghent were transformed into cosmopolitan hubs. This marked a definitive moment in art history, leading artists to gain star status and paintings to become objects of desire.

“When you have money, you want to spend it, and a great way to do so is to buy art for the walls of your new house,” said Chloé M. Pelletier, the curator of “Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: Three Hundred Years of Flemish Masterworks,” an exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts running til October 20. The exhibition displays 137 artworks from this period, as well as drawings, sculptures and prints. Its title references archetypes depicted by painters Pieter Bruegel, Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens (as well as many others), in addition to showing religious devotion, they painted everyday scenes of life — and everyday vanities.

Not unlike posting meticulously orchestrated snippets of an Amalfi vacation or a luxe wedding on Instagram today, a burgeoning collector of the era seeking public attention could show off their wealth by sitting for a portrait that radiated ostentatious triumph and prosperity. Take a mid-17th-century painting by Michaelina Wautier, for instance, which depicts a sitter in a black silk shirt posing in front of a painting he’d acquired by Rubens.

This new class of collectors ushered in the art market that we recognize today. Freed from the long-standing tradition of creating work upon requests for religious and aristocratic patrons, artists began making paintings on spec — to be promoted and sold by a then newly established profession: the art dealer.

The scenes of the era were both divine and mundane, from Hans Memling’s luminous nativity scene, circa 1480, to Bruegel’s depiction of an angry wife hauling home her intoxicated husband, circa 1620. A scene or subject’s popularity could prompt 10 or more similar versions — whether of drunk bar brawls or the baby Jesus.

As the growing new-monied class chased lighthearted illustrations of the everyday to show off wealth, the growing prominence of the printing machine boosted the circulation of these captivating paintings from collectors’ homes to those of everyday people, and even to the streets. In other words, this new method of mass dissemination made them go viral.

Stephanie Porras, art historian and author of “The First Viral Images: Maerten de Vos, Antwerp Print, and the Early Modern Globe,” told CNN in an email that the idea of virality “seems to open up (a) way of thinking about issues that art historians hadn’t traditionally considered: the ways in which the movement of images can be shaped and funneled through gate keepers and social networks.”

Art collectors at the time possessed an average of 30 paintings at home, noted Pelletier; a common party pastime during social gatherings was to guess a work’s painter, or whether the maker was the master or an apprentice.

“These were conversation pieces that you could talk in front of and laugh at,” she said. The curator considers the buzz around art stars and chroniclers of new Flemish lifestyle “an early moment of pop culture.”

Art for art’s sake

Engagement in the art world was also an early opportunity for self-branding and promotion. “Elegant Couple in an Art Cabinet,” painted around 1675 by Peeter Neeffs the Younger and Gillis van Tillborch, for example, depicts the subjects surrounded by a towering orchestration of their collection in the heart of a palatial residence — the #richkidsoftherenaissance, perhaps.

“They were interested in showing their best sides to build a self-image,” Pelletier explained of these old-school influencers. On the flip side, however, pious subjects signaled a grounding of the egos in respect for the divine, with “memento mori” details, such as a skull or a Bible quote in Latin, promoting humbleness and awareness of mortality. “They liked to demonstrate their lifestyles, but also wanted to affirm they were virtuous Christians who knew nice clothes and houses faded,” she added.

The overtness of a viral statement, similar to any trending topic or figure on social media today, faced occasional retaliation; dismay or snark from the peanut gallery was commonplace. The curator notes that reactions to a freshly unveiled painting included satirical commentary or comical illustrations circulated on pamphlet — or perhaps even an oral takedown in the town square.

“Art was the ultimate form of entertainment and social spectacle,” Pelletier said.

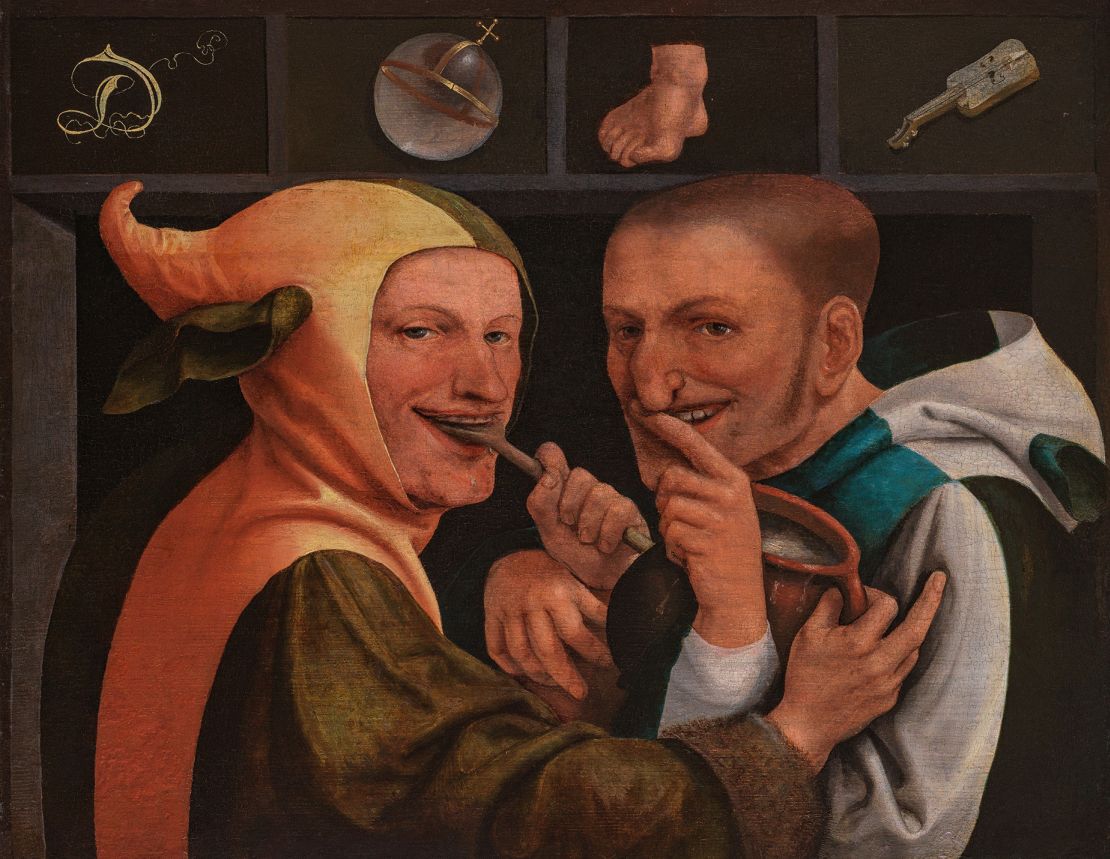

There was plenty of humor too, “if you were in on the joke,” she added. A circa 1530 work from Jan Massys shows two men with carefree smirks, playing with a bowl of porridge, for example. Above them are four icons: the letter D, a globe, a foot and a violin.

They mark a puzzle for the viewer to decode — when uttered out loud in Dutch, the quartet rhymes with “the world feeds many fools,” thanks to the similarity of the words for foot and feed. (The phrase is also the painting’s title.)

Playing to the gallery

But as much as staged glamour or coded banter, false information also spread into public consciousness through viral imagery. Fraudulent narratives about Indigenous people, such as that cannibalism was rife among the Caribbeans, helped to justify colonization of the new world; the exhibition includes artworks depicting this fear-mongering — including Jan van der Straet’s late-16th-century engraving of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci encountering people roasting a human leg — and makes a potent case about the impact of a misinformed image, whether crafted with imperialist strategies then, or now through AI.

Today, we’re no stranger to how images are used to self-fashion, virtue signal and spread harmful ideas online. But it was newer territory then, as paintings provided the public a visual vocabulary to internalize a rapidly changing social landscape.

The faster spread of images prompted the abundance of knowledge — useful, misleading or silly — similar to the contemporary flux of data that ceaselessly penetrates today into our consciousness. And the art historian Porras sees a clear connection between the era’s artworks and contemporary viral images with malleable readings.

“For us, it’s clear how a viral meme or format can be re-scripted and performed so that it moves so far from its original context as to be unrecognizable,” she said. She makes her case vivid with a familiar example, as opposed to a scene of 400-year old mundane debauchery: “Think of all the riffs on the jealous girlfriend meme, which comes from a standard photo stock collection.”