On October 4, 1883, the legendary Orient Express departed Gare de l’Est in Paris for the very first time, slowly winding through Europe on its way to Constantinople, as Istanbul was then known. During a seven-day round trip, the service’s 40 passengers — including several prominent writers and dignitaries — lived in mahogany-paneled comfort, whiling away the hours in smoking compartments and armchairs upholstered in soft Spanish leather.

The most luxurious experience of them all, however, could be found in the dining car.

With a menu spanning oysters, chicken chasseur, turbot with green sauce and much else besides, the offering was so extravagant that part of a baggage car had to be repurposed to make space for an extra icebox containing food and alcohol. Served by impeccably dressed waiters, guests sipped from crystal goblets and ate from fine porcelain using silver cutlery. The restaurant’s interior was decorated with silk draperies, while artworks hung in the spaces between windows.

As newspaper correspondent Henri Opper de Blowitz, one of the maiden journey’s passengers, wrote: “The bright-white tablecloths and napkins, artistically and coquettishly folded by the sommeliers, the glittering glasses, the ruby red and topaz white wine, the crystal-clear water decanters and the silver capsules of the Champagne bottles — they blind the eyes of the public both inside and outside.”

The Orient Express’ opulent passenger experience was later immortalized in popular culture by authors like Graham Greene and Agatha Christie. But dining on the move was very much a triumph of logistics and engineering. Just four decades earlier, the very idea of preparing and serving hot meals aboard a train would have been almost unthinkable.

In the early days of rail travel, passengers would either bring their own food or, if scheduled stops permitted, eat at station cafes. In Britain, for instance, meals were served in so-called railway refreshment rooms from the 1840s, though the quality was often questionable. Charles Dickens, a frequent traveler on the UK’s railroads, recounted a visit to one such establishment, where he purchased a pork pie comprising “glutinous lumps of gristle and grease” that he “extort(ed) from an iron-bound quarry, with a fork, as if I were farming an inhospitable soil.”

A new era

The British may have pioneered rail engineering in the 19th century, but the dining car’s story begins in America.

In 1865, engineer and industrialist George Pullman ushered in a new era of comfort with his Pullman sleepers, or “palace cars,” and then launching a “hotel on wheels,” called the President, two years later. The latter was the first train car to offer on-board meals, including regional specialties like gumbo, which were prepared in a 3-foot-by-6 foot kitchen.

Pullman followed his hugely successful President with the first ever dining-only car, the Delmonico, which was named after the New York restaurant considered to be America’s first fine dining establishment. By the 1870s, dining cars could be found on sleeper trains across North America.

But it was Belgian civil engineer and businessman Georges Nagelmackers who brought the idea to Europe and elevated the experience to new heights.

He saw the potential for luxury sleepers in Europe and set about transforming rail travel on the continent with the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL, or just Wagons-Lits), founded in 1872.

The firm quickly began producing the world’s most glamorous dining and saloon cars — not only for its famous Orient Express but also the Nord Express (from Paris to Saint Petersburg), Sud Express (from Paris to Lisbon) and dozens of other services, as the company came to dominate luxury rail travel in mainland Europe by the turn of the 20th century. Wagons-Lits also operated grand hotels along its routes, though the on-board dining remained central to the romantic appeal of train travel.

Meals were served at set times and were supervised by a ma?tre d’hotel. And from the table service to the decor, the carriages embodied the French art of living, according to Arthur Mettetal, who recently curated an exhibition about the history of Wagon-Lits’ dining cars at the Les Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in France.

“With the different menus, it was the same as (what) you could have at a really nice Parisian restaurant,” he told CNN on a video call. “Also, the tableware, the silverware, the decoration — everything combined was what was considered luxury at this time.”

Golden age

The 1920s are considered a “golden age” for rail travel in the West. As Europe emerged from the ravages of World War I, business travelers and adventurous vacationers began taking advantage of smoother, quieter and faster steam trains.

As Wagons-Lits’ routes reached into North Africa and the Middle East, state-of-the-art metal cars replaced the old wooden ones. Celebrated artists and designers were meanwhile commissioned to decorate the cars, including the palatial dining ones.

By the end of the next decade, the company was operating over 700 dining cars — yet, an even greater on-board luxury had emerged by then: eating in one’s seat.

Known as the Pullman lounges (the American industrialist’s name had, by that point, become a byword for luxury train travel), Wagons-Lits’ new car was introduced on various daytime services. Rather than waiting for lunchtime or dinner slots, passengers were served food directly to huge, winged chairs with comfortable headrests. The cars proved “revolutionary,” said Mettetal, describing them as “the most luxurious carriages ever created.”

Wagons-Lits turned to decorator René Prou and master glassmaker René Lalique to design the Orient Express’ new Pullman cars. They featured elegant marquetry and molded glass panels, and even the luggage racks “were transformed into gems of Art Deco,” read Mettetal’s exhibition notes.

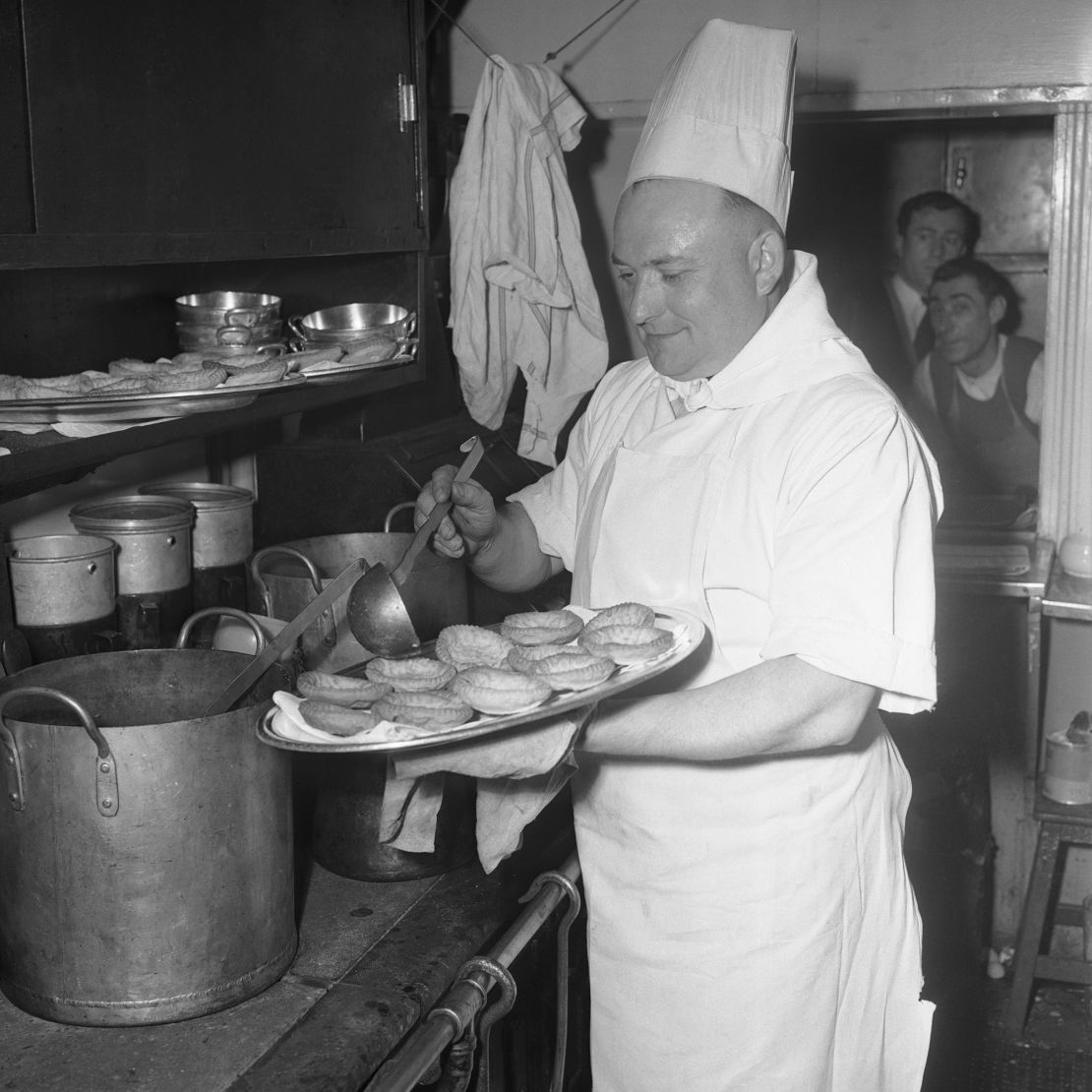

The ease and convenience of dining on Wagons-Lits belied a complex logistical operation. From 1919, the company operated a central kitchen within a Paris hotel that prepared (and sometimes pre-cooked) food bound for its train network, reducing the burden on onboard chefs.

“Inside the dining car, the kitchen was only seven or eight square meters (75 to 86 square feet), so it was really difficult to prepare food for more than 100 people,” said Mettetal.

With the help of this off-site kitchen, Wagons-Lits was serving around 2.5 million meals annually by 1947. But this decentralized production model also contained the seed of dining car’s ultimate demise.

Slow decline

After World War II, the way railroads and passengers operated both underwent significant changes. Trains became faster, reducing the spare time that travelers had to kill during journeys; the rise of commercial air travel and an explosion in personal car ownership across Europe in the 1950s meant that trains were no longer considered the most luxurious way to travel.

The economics of food production also evolved in line with the model pioneered by airlines, whereby meals were entirely prepared off-site (and eventually eaten from compartmentalized plastic platters with disposable cutlery and napkins). In 1956, Wagons-Lits opened a new, modern industrial kitchen, equipped with large-scale refrigeration systems and meat storage containers, in which over 250 staff prepared food for all trains departing Paris.

Eating slipped down travelers’ priority lists. In turn, Wagons-Lits’ offerings came to value convenience over comfort, including self-service buffet cars filled with cheaper, cafeteria-style food. In the 1960s, the company launched portable “minibars” — initially selling 23 products, including sandwiches — that were rolled through the train, offering food to seated passengers at eye level.

When it came to food, train operators began selling the idea of modernity and innovation, not opulence, said Mettetal, whose exhibition (and an accompanying book) features advertising photos from the archives of the now-defunct Wagons-Lits and France’s state railway, SNCF. Take a 1966 promotional image (pictured top) of a dining area on Le Capitole, a Wagons-Lits express between Paris and Toulouse, that includes the train’s speedometer clearly in shot.

“It’s an image that promotes (the idea) that it’s possible to eat on a train traveling at more than 200 kilometers per hour,” Mettetal said. “But also, it shows only the family, with a couple and just one child, so it’s totally different. It’s a new type of passenger, sociologically.”

By the 1970s and 1980s, kitchens had largely disappeared from Europe’s railroads. And despite a revival of interest in train travel on the continent, dining cars (or certainly those equipped with kitchens) are now largely the preserve of tourist services. Many of them?capitalize on nostalgia — like the new Orient Express service, which is being revived in 2025 with a dining car its website claims “reinterprets the codes of the legendary train” — offering a chance to revisit a time when dining on a train was not just a luxury, but the luxury.