On November 9th, 1985, Princess Diana and Prince Charles were honored guests at a White House dinner hosted by then President and First Lady Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

This was a gala dinner as only the White House can provide. The first couple standing outside on a cold night, eagerly greeting British guests. It was an evening of high glamor, the largely showbusiness guest list chosen by Mrs. Reagan.

Imagine tuxes, ball gowns, real royalty, and Hollywood royalty. It was Diana's first trip to the United States.

Well, I didn't know it was going to happen until I got there. And then Mrs. Reagan, the president's wife, tapped me on the shoulder and said, May I speak to you for a moment?

That's John Travolta recounting the evening to CNN at the Cannes Film Festival back in 2018. Turns out he had been invited to the event by the first lady for a very specific reason, and it had to do with Diana.

It's the princess's wish, only wish, to dance with you. That was her only wish in visiting this country. Would you do that as a gesture to her? Really, that's her only wish? It's her only wish. I said okay when am I supposed to do this kind of thing? And she said, Well, around midnight, believe it or not. Like a fairy tale. And she said, I'll come get you. So, of course, for 3 hours, I'm trying to recall images of her and Charles dancing and how they danced and how I would be different. So I clocked all that and I thought, Well, I'll just go back to the days that you were taught how to do your ballroom dancing, and you'll you'll figure it out, John. And I did. And it was glorious because when I went up and I tapped on her shoulder and said, Would you care to dance with me? She got blush red, and she said, I would love to. It went on and on, and they did a collection of Grease and Saturday Night Fever songs. It was a live orchestra and we probably danced for about 15 minutes.

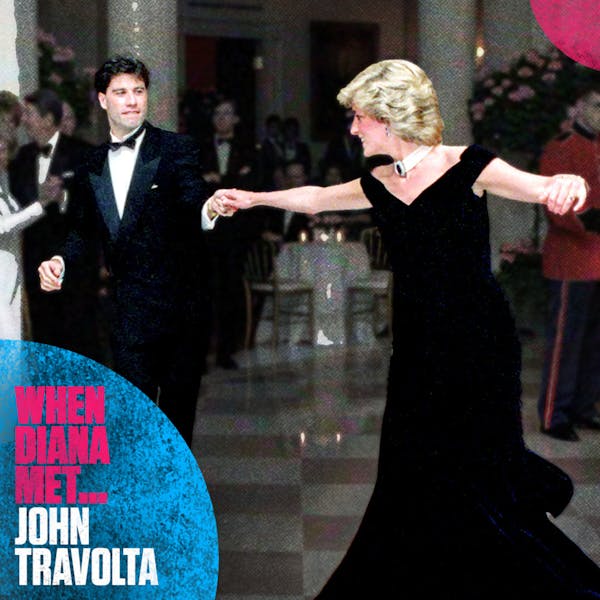

The photos and video of Diana swirling on the dance floor with Travolta are legendary. She's in a floor length off the shoulder gown made of midnight blue velvet with a pearl choker around her neck. That woman loved a choker. And I have to say, she looks like she's having a lot of fun. Very quickly, the media ate the story up. The Cool Princess, dancing with the cool movie star. So the young people listening, you have to know John Travolta was huge. Imagine Channing Tatum and Harry Styles had a dance baby, that was John Travolta. I can't help but think this is like a high school prom except for celebrities. But if we were to believe Travolta's version of the story, this was Diana's fantasy. That night on the White House dance floor, Diana wasn't the object of our fairy tale narratives fueled by Disney princesses, she was apparently living her own.

Or was she? We don't know for sure what she wanted or was thinking. We know what the media focused on and we know what came next. Diana was, of course, a world famous princess. But if there were any doubts that she was Capital C celebrity, well, those doubts were now gone. This is the night she joined the big leagues and proved she was not simply a member of the royal family, she could hold her own among America's royals. But there's more to the story. I'm Aminatou Sow and this is the fifth episode of When Diana Met...John Travolta. In the weeks before Diana and Charles arrived in Washington, D.C., to be honored by the Reagans, they'd been on an extended royal visit to Australia, so the White House dinner came at the tail end of a long work trip for them. They were jet lagged. And despite the dancing and the glamor, this, too, was a work event.

They were always big events because these events are seen as very important in terms of bilateral relationships for the UK. I think there's the fascination that Americans have as well with royalty, and so that would have been a real buzz because it's, you know, the future king and queen going to the White House, meeting the President and first lady.

Max Foster is CNN's royal correspondent.

And Diana was the world's biggest star, I think, at that time, and so there was a huge amount of media attention on that moment, and you had Hollywood royalty invited as well, had all the elements you would hope to get from a royal visit, I think.

The guest list read like a who's who of a certain brand of eighties cultural figure, the explorer, Jacques Cousteau, the Olympic skater, Dorothy Hamill, the socialite Gloria Vanderbilt. The opera singer Leontyne Price performed that night, and she was joined by her brother, retired Army General George B Price. They were the only two guests who were African-American. And when Diana sat down to dinner that evening, she would find her idol, the ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov, seated next to her.

What's fascinating is that it wasn't just about John Travolta. It was a state dinner, effectively and there were lots of important people that the president and first lady wanted to meet the royal couple. But over time, it has become just about that Travolta dance.

Travolta was actually one of four men in particular who danced with Diana. Clint Eastwood, Neil Diamond and Tom Selleck were the others. Each one typified a kind of white American male ideal. Clint had the eyes. Neil had the voice. And Tom Selleck had the mustache. And Diana would dance with all of them. Then White House photographer Pete Souza photographed the event and noted that though Diana danced all night long, she did not, however, dance with her husband, Prince Charles. It's the pictures of her with Travolta, with her outstretched arm, as though she's twirled away from him for a moment, only to soon twirl back that endure.

At the time, I think you would have seen, you know, the most famous woman in the world, Dancing with John Travolta, who was also very famous but was very relatable, you know, he's the everyman and there's always one of the characters in one of his movies I think men can relate to a lot of women can relate to as well.

So Diana, who was already known to be a relatable royal, was made even more relatable through this dance with Travolta.

What's interesting about those photos is that they've almost matured and become more relevant over the years. And obviously that's a lot to do with the fact that we later on found out what sort of state of mind Diana was in at the time. We now know that this was right in the middle of her suicidal period where she was most unhappy in her marriage, so she was very, very unhappy.

Max is referring to a section in Andrew Morton's book. We now know she struggled with an eating disorder and depressive episodes that weren't treated until 1988. This White House dinner occurred in 1985 so she was in the midst of all of that emotional turmoil. But back then, we didn't know all that and we certainly couldn't see it from the photos of that night.

She looked free. She looked confident. It was a dance of defiance, in a way. She hit the dance floor with the most famous men in the world. And, you know, the reality is and she knew this as well as anyone, that you do not steal the show from the senior royal. So you look back on that moment, and I think for a lot of people, she's seen as strong, it's not just she looked amazing, it was this moment, defiance and freedom and confidence and strength I think that really comes from it and the more we learned about how unhappy she was, it becomes more poignant.

Yeah, I'm so struck by hearing you say that she knows that you shouldn't steal the spotlight from the Senior Royal. But the truth is that she is the main attraction everywhere she goes.

She was an aristocrat she fully understood how society worked, you know, he's going to go on to be king. So, you know, there's a national interest, arguably, to always put him in the spotlight out front. She could have stepped back. She could have not done the dance in front of the cameras and looked at the cameras, couldn't she? So she chose to do that. It looks to me, as like a almost a survival moment, a strength moment and I think that's what endeared her to so many people, that she wasn't going to be suppressed by the system.

This bit about not being suppressed by the system is just the kind of thing that Americans love. It no doubt helps catapult her to American celebrity status. That's when she was an hemmed in by formality. We love that stuff here. And for Diana in 85, that must have felt great. In the U.K., where royal protocol dictated her every move, she was dogged in the press for any perceived misstep. Privately, she was in her own sort of torture, as we know she was having thoughts of self-harm at the time and was terribly unhappy. In the United States, her identity became that of a celebrity, an uber celebrity, not just a royal wife or mother. Put it this way. People magazine, which specializes in the personal lives of celebrities, had already put her on the cover ten times by the time of this White House event. As of summer 2021, she'd appeared on the cover of People 59 times. That's more than anyone else. Diana became and still is, a celebrity among celebrities. That gave her a power separate from the family.

She understood the media and also she was so authentic, you know, we talk about authenticity in modern media, but she, you know, did that years before a lot of other famous people or before we even started talking about it. And she was doing a huge amount of good as well. So I think it was very easy for Americans to look at all the positives. But ultimately, I think that they completely fell in love with Diana and that's why the monarchy was in such a bad state after she died. And I think the way she campaigned was her big legacy, really. I think even some of the big celebrities today probably aren't fully aware that, you know, they're picking up on the way that she did it in many ways because it wasn't done in that way before.

Yeah. You know, another thing that's really interesting about her is that she does straddle the line between celebrity and also obviously a member of the royal family, and that is- we feel the effects of that I think the most in the United States with how people just really think about, about her and the family. I'm wondering if you can talk a little bit about what the public is looking for when we think about someone like this who is like a celebrity but also has a different kind of cachet.

Well, it depends what perspective, whether it comes from the U.K. or U.S.. I think one of the things that particularly fascinates the U.S. about royalty is that it's, you know, in many parts of America, very celebrity culture and royalty is almost a level above celebrity. So it's unattainable. You're all brought up to be told that anything's possible, but actually you can't just become a princess or a queen because you have to be married into that system. So that's where the fascination comes, I think, and, you know, I've been on red carpets where you got Hollywood A-listers and studio bosses, you know, who don't kowtow to anyone kowtowing to royalty. And I find that fascinating. So I think it's just that unattainable level of celebrity and I think there's a bit of frustration, but fascination as well.

That frustration and fascination are, of course, fueled by the outsized media attention Diana commands. At its best, it helped her shine a light on causes she cared about, but at its worst, this media attention led to her death.

Whilst the media was her biggest curse, probably, and her sons would blame the media for killing her ultimately, I think it was also her greatest asset and she understood that and she was constantly trying to use it for good, I think

When we come back, we get into the complexity of Diana's relationship with the media and we get into where we, the audience fit in.

The circumstances of Diana's death on August 31st, 1997, are well known. She and her boyfriend, Dodi Al Fayed, were being driven frantically through the streets of Paris, trying to outrun paparazzi on motorbikes when their car crashed.

In France, much of the attention is on the car crash that killed Diana and two others.

Three more photographers were added to a list of those being investigated by Paris police for whatever role they may have played.

Authorities have launched a formal investigation for charges that include involuntary manslaughter and failure to give aid.

She was the victim of this technologies, appetites, expectations and obsession.

Her celebrity had become a hot commodity. At the time of Diana's death, a photo of her could go for up to $500,000 and if she was with a boyfriend or possible lover, that could drive the price up to $1,000,000. The tabloid media is obsessed with celebrity sexual and romantic exploits, whether they exist or not.

Well, certainly. I mean, Diana is like a woman who literally died at the hands of the paparazzi. You know, she literally paid with her life for the public's desire to know everything about her. And so she is in some ways, even before Britney, before Lindsay Lohan, before all these, like, broken starlets, she is perhaps one of the first or the first prominent victim of celebrity culture.

Naomi Fry is a New Yorker staff writer who covers art books and pop culture and she's someone who can talk in a smart way about celebrity gossip. This battle that Diana waged as a celebrity who was constantly in the crosshairs of the cameras and who paid the ultimate price is, frankly, why I feel conflicted every time I look at a photo of her.

People's desire to know so much about celebrities, to go so deep and so far into their stories that we literally kill them, whether actually or kind of spiritually. It's a difficult place as someone who's very involved in caring about celebrity culture, even just as a you know, as a casual consumer, but also as a writer who often talks about it. I don't know that it's resolved for me, you know? Yeah, that question, you know, my own complicity in this whole structure.

From 2007 to 2011, Naomi was a fact checker for US Weekly, a celebrity gossip magazine, trafficking and baby bumps and boyfriends. US Weekly has a signature sections you're familiar with like "Stars, they're just like us" and signature issues like the Hot Hollywood Special and the Best Body Issue. Even if you don't pick up this magazine at a grocery store, I bet you're aware of what's in its pages.

I think the narratives that a magazine like US Weekly was drawn to was, of course, as dramatic as possible, you know, the ultra dramatic sells, and so it really lent itself into something we're talking about a lot, I think, in relation to Britney Spears, you know, especially recently about how much the tabloid press kind of turned her into a tragic figure in some ways, but also a figure of ridicule and a figure that deserved extremely harsh judgment where she could do no right at certain points in her career, which led to a kind of dehumanizing stance towards her. And, of course, other figures in the same way weren't vilified, but were deified. You know, but I could definitely see the figure of Diana as part of that marketplace, whether it's being bad, being cast as like a villain in whatever drama is being discussed, or once you move on to the other side, you might become this sort of like guardian angel, you know, like Diana is like William and Harry's guardian angel. Sure. Now that she's no longer with us, it's easier to look at her as a kind of icon, as a kind of suffering saint. So thinking about women, especially in tabloids, as either like a whore or a saint, is a very surefire way to attract the public's interest.

I mean, there's so much to unpack there. Like we repeatedly call her a celebrity, and she is a celebrity, but I also think that she, like, redefined a new kind of celebrity, because let's be real here. Like, the royals are not entertainers, there's not really a talent there. You know, and ostensibly, they're supposed to be kind of above all, there's like really low rent about them, like being involved in celebrity culture, but yet the coverage of them, you're not seeing these stories in the political section, it's 100% tabloids. And that is also, I guess, like it's strange, but also it makes sense.

That's a really good point, I think with the royal family, and you see that push and pull in, you know, contemporary accounts of it, like in The Crown, for instance, you know, part of the, of the conflict that Charles like poor, big eared, relatively charmless, Charles was jealous of Diana's kind of natural star power slipping into this figure of the modern celebrity, whereas he was sort of left behind and became less interesting and I think that conflict, whether you have it or you don't with the royals, is kind of interesting because for instance, now with Harry and Meghan, right? I mean, they in some ways and arguably have that. But now that they're in America and they're doing like the Oprah stuff, and I think there is seemingly a lot of anger at them from England. You read these like Piers Morgan, you know, columns in The Daily Mail or something where I think part of the argument is it's like it's Hollywood Harry. This actress has kind of grabbed this British boy and is making him into a fame whore, right?

Like, are the royals above this, are the royals not above this is the question I think that's being constantly litigated, while, of course, recognizing that in order for the royalty to survive and remain possible, you do need that star power, because if everybody was like Charles, why would anyone want to look at the royals? Right. And looking at this is the currency of contemporary culture.

I mean, that that is so interesting. Like in this conversation about whether they're celebrities or not, what is true is that there is a direct line between their treatment as celebrities and the ushering of influencer culture in the way that we know it now. Because one of the arguments that people make against the Kardashian family all the time is what is their talent? Like what do they do?

And Kanye would say that Kim's talent is that she's beautiful, other people would say that she is a shrewd interpreter. And yet and with Diana, there was a talent. She was very good with people. She could connect with the public. She could. Whether it was calculated or not, that is I think we recognized today that kind of emotional intelligence is a currency and it is an asset and it is also a talent, and it's clearly a talent that other members of the family did not have, which is perhaps why she is also a standout. But yeah, I do think that so much of the influence or culture tension is so palpable in her story, because here is someone who like has a platform before we call them platforms. I don't quite know what to make of it, but it feels so palpable to me.

That's such an interesting point that I never even thought about that you just raised that the royal family or Diana, specifically with her kind of attractiveness, charisma, talent for forming relationships with people, was an early influencer because the question like, but what does she do exactly? I mean, she does charity, she did good by working to dismantle like landmines, you know, I mean, she she did do things that on the world stage are arguably more valuable than just like taking pictures on Instagram.

I know about things that are now very performative aspects of how you're supposed to be a celebrity, right? If you are a celebrity with a platform, you're supposed to have a cause. Every big deal celebrity has some sort of like U.N. peacekeeping ambassador situation and in some ways, you know, like she really made that popular. And I'm not saying that it was not sincere, it is a sincere expression of her-

No, no, no, no. But that's, it's, that's such an interesting- that's such an interesting point, because I guess also, if you say that influencers nowadays, they sell whatever brands they partner with. Right? They sell their own personality, their own charisma, their own good looks and so on, for the benefit of whatever brand it is that they're working with. And for Diana, ultimately, I mean, first, the brand that she was working with was the royal family, right? If she was like the beautiful English rose, the young bride who Charles married and and became very popular with the public. It, of course, the stock of the royal family, rose because of her, right? Because of her influence and her presentation of a certain type of femininity, a certain type of warmth, a certain type of just like her personality, her skills with people. But then, I guess, you know, after she left the royal family, she became kind of like her brand was herself. You know, she had an enormous brand. It just, just as herself as a woman freed from the shackles of, of the royal family who had the strength to get up and leave as a mother and so on, you know, I hadn't really thought about, like, what, an influencer can really be, you know, and how being an influencer is not like an idea that was born like eight years ago you know? It's in fact a much older profession, so to speak and it might have started with the royals.

I mean, you know, something to chew on there. You know, I want to go back a little bit and ask you, like, how do you define your own relationship with celebrity and how would you define the relationship between the public and celebrities?

I would say that probably what animates me and my relationship to celebrities is similar to what animates most people, which is like a fascination with something that, from the outside, might appear seamless and and glamorous and unreachable and untouchable and isn't marred by the struggles of everyday life that we all face, but I think there's also the concurrent desire to kind of disrupt that surface, right? Which is where, say, tabloid journalism comes in, right. What are the secrets behind the mask? We want to know. The whole like stars are just like us trope, which could be like they go to the ATM, you know, they fill up on gas, you know, like these mundane things, but could also be they suffer and maybe their suffering is no less great than ours.

And like, it's not as fancy as you think it is, and everyone is struggling, you know, and somehow that the media creates this narrative where you're supposed to root for some people and not roots for others and I'm really struggling with this as a consumer of this media, because I think that while it is true that media like shape stories, we have an appetite for it, like they there is no supply without demand. And so I'm just really trying to figure out, like, where does the complicity lie with the consumer and where is the responsibility for the media?

Yeah. With the complicity, I mean, listen, I think in the grand scheme of things, I give myself and everyone else a bit of a pass for like reading The Daily Mail when they're like in their fking shitty job, you know, or whatever it is, and they just want a little bit of entertainment, like just to watch a photo of like beautiful people in bikinis on like a yacht in Capri, I think it's not that terrible. It's not great, but it's not that terrible. The consumer isn't making money off these things. No, that's that's that's first of all, you know, someone else is making the money. But I don't know that this attitude of consuming these things is what is to blame for what people believe. It's complicit in it, but it's not the source of it, I guess I would say. It keeps the machine churning, certainly.

You wrote this, "if Prince Harry and Meghan Markle solidify their brand in this manner, publishing a book, hosting a talk show, selling clothing, homewares, or even cleaning products, it will surely not be long before they transform from British to American royalty." So I-

First of all, I was like, wow, publishing a book, hosting a talk show, selling clothing. I was like, the Obamas are doing it, the Clintons are doing it, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle are doing it, it is truly the job of the public figure. It is now de rigueur for anyone who straddles the blurry line between political figure and celebrity to run their own content factories. The Obamas have Higher Ground Production, Hillary Clinton and Chelsea Clinton have Hidden Light Productions, and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle run Archwell Productions. All these people are also podcasters now, we have the same job, love to see it.

But I guess I'm wondering, like, what is American royalty? And do you think that Diana was American royalty? Because a lot of people that I've spoken to for the podcast all said that she was not a celebrity until she came to America, it was really our media and our public that catapulted her, and I have complicated feelings about that because she is like known around the world you know, there is an entire commonwealth of people that could have done that for her, but this particular kind of celebrity does feel American.

Yeah, I think there is like to be American royalty, I think is to be like Oprah, you know, to be like someone who is not necessarily to the manor born right, but who has managed to ascend and become this figure that can sell us anything.

Celebrities like Oprah and Princess Diana have something very special and common. They're portrayed as people whose authenticity we can trust. Unlike Oprah, though, most of our experience with Diana then and now has been looking at images of her. These images still hold power and are widely circulated on social media today. More on that after the break.

You said something really interesting earlier, that looking is the currency of contemporary culture and I'm wondering if you can expand on that and how it applies to Diana specifically?

Yeah, I mean, I think the visual, especially if we think about social media, you know, this is just kind of anecdotal. But you know how when you're like scrolling Instagram and maybe you're like sleeping partner is by your side or your child or your friend, or you just don't feel like turning on the volume on your phone and you still get most of the experience just from looking right? The predominant path to engagement is through the visual right, it's like, oh, I saw that, yeah. And I think that there's something that transcends language even about it, you know, that you can see- someone from another country can see a picture of Diana, and even if they don't understand her words or can read anything that's written about her, they would still know who she is, there's something very primal about that. And I think Diana is an example of a celebrity who was just, like, extremely visually captivating.

Her look, I think I saw someone post, but it was like a side by side of Kristen Stewart playing Diana and a picture of Diana herself and they said something about her hair, how there is something so singular about the way Diana's hair looked that you can't really replicate it, it was just so visually distinct, like its height, its width, its texture, you know, its color. It's, it was recognizably Diana, you know, and when you're like the People's Princess, you depend most of all on people seeing you, seeing your image. That's how you connect to people, with your smile, with your signature outfits you have, with the signature hair that you have with your whole bodily manner. I think that's very important to the notion of celebrity and Diana's an example that.

Mhm. Naomi Fry, thank you so much for joining us today. This was really, really cool.

Oh, my God, thank you for having me. Thanks, Amina.

Oh, my God. I love it. We're going to make a Diana head out of you. So this makes me really-

Oh, my God. I mean, I love Diana.

This takes us back to that White House dinner and Diana's dance with John Travolta. At the time, Diana was a member of the royal family, famous and known, but she was not quite the icon we consider her today. The American media made her that, it influenced how the U.K. and the rest of the world saw her, and it snowballed from there. When her marriage to Charles falls apart in 1992, it snowballs even more. She is catapulted to a level of fame that's hard to understand today. The media hounds her with the excuse that the public loves her and the public cannot help but to cling on to the, quote, unquote, fairy tale narrative she stands for. To go deeper on this allegorical take on the princess and her fairy tale, let's go back to CNN's royal correspondent, Max Foster. Could you describe how Diana feeds into the princess fantasy and pop culture and fairy tales?

I don't want to generalize too much, but if you imagine a young girl who has grown up watching Disney movies or any sort of movies, and you can really break that down even more to the underdog narrative that is so prevalent in Hollywood now, which defines a lot of world culture. You see someone who embodies that princess idea in every way when she marries Prince Charles at St. Paul's Cathedral. And a lot of the narrative at the time, if you remember, was that she was a commoner. She wasn't royal. And I think, you know, the palace did sort of see this as this moment of reinvention for the British monarchy. So it lived up to all, everything you'd imagine of a fairytale wedding. But the more powerful part was later on when the marriage broke down and the sense that she was wronged and how she wouldn't accept being wronged by the establishment and taking on the establishment. And that's when the underdog story sort of sweeps in, I think. And that's the thing- that's the part of the story that really lives on and people are really inspired by. And the system did work against her, she had the whole system against her and she fought back and I'm sure she didn't do everything perfectly, but I think that's what endears people to her. So I think she was a true fairy tale princess, but it wasn't quite in the traditional narrative, it's sort of turned around a bit.

The concept of a quote unquote fairy tale constantly comes up when talking about Diana. The version Max sees is of the heroine fighting back against the system, and she did try to do that with the media. There had always been rules between the press and the royals, but the frenzy around Diana changed the game. The old rules didn't apply anymore and by 1993, Diana was hoping to get some distance. She made one last ditch Hail Mary effort by surprising the world with this statement at a charity luncheon.

When I started my public life 12 years ago, I understood the media might be interested in what I did. I realized then their attention would inevitably focus on both our private and public lives. But I was not aware of how overwhelming that attention would become, nor the extent to which it would affect both my public duties and my personal life in a manner that's been hard to bear.

But we know she didn't get the privacy she was looking for. The insatiable hunger for her and details about her life were completely out of her control. Turns out she was in a fairy tale after all. Not the Disney kind with the castle in Prince Charming, but the darker German kind, a brothers Grimm story. And in her story, the beast was always going to win, it was everywhere. Her family chose to bury her on the grounds of Althorp Park, her family home. Her brother, Earl Spencer, made the change when it became clear the media and public would continue hounding Diana. The family wanted her to have the respect and privacy and death she wasn't afforded in life, that's the one thing that gets me any kind of peace about this situation. But as I mentioned before, Diana did have some success with using the media and her images in order to express something important, especially when it comes to her clothing.

Next time on When Diana Met, what was she trying to say with this black dress, this black sheep sweater, her gigantic puffy wedding dress? What did she want us to know about who she was?

Elizabeth Emanuel

00:35:46

She became a fashion icon, and we were there right in the early days and we could see her grow into that. We were very lucky and very honored really to have been part of that and to have known her then.

When Diana Met is produced by CNN Audio and Pineapple Street Studios. It's hosted by me, Aminatou Sow. Our producers are Mary Knauf, Tamika Adams, and Erin Kelly. Our associate producer is Marialexa Kavanaugh and our editor is Darby Maloney. Mixed and original music by Hannis Brown. Our fact checker is Francis Carr. Additional support for the series comes from Ashley Lusk, Kira Boden-Gologorsky, Alexander McCall, Lisa Namerow, Robert Mathers and Molly Harrington. Executive producers for Pineapple Street Studios are Bari Finkel, Jenna Weiss-Berman and Max Linsky. Megan Marcus is the executive producer for CNN Audio.