Slavery’s last stronghold

Mauritania’s endless sea of sand dunes hides an open secret: An estimated 10% to 20% of the population lives in slavery. But as one woman’s journey shows, the first step toward freedom is realizing you’re enslaved.

In 1981, Mauritania became the last country in the world to abolish slavery. Activists are arrested for fighting the practice. The government denies it exists.

“On this land, everybody is exploited.” The vast Saharan nation didn't make slavery a crime until 2007. Only one slave owner has been successfully prosecuted.

Moulkheir Mint Yarba escaped slavery in 2010. She has asked the Mauritanian courts to prosecute her slave masters. "I demand justice," she says, "justice for my daughter that they killed and justice for all the time they spent beating and abusing me."

Mauritania by the numbers

Slavery

Slavery

- Population: 3.4 million

- Percentage living in slavery: 10% to 20%

- Enslaved population: 340,000 to 680,000

- Year slavery was abolished: 1981

- Year slavery became a crime: 2007

- Convictions against slave owners: One

Geography

- Area: 400,000 square miles, slightly larger than Egypt

- Capital: Nouakchott

- Bordered by: Mali, Senegal, Algeria, Western Sahara

- Landscape: Sahara Desert, Sahel

- Farmable land: 0.2%

People

- Languages: Arabic, French and regional languages

- Official religion: Islam

- Literacy rate: 51%

- Unemployment: 30%

- Population density: 8 people per square mile

ECONOMY

- Percentage living on less than $2 per day: 44%

- GDP (purchasing power parity): $7.2 billion, less than Haiti

- GDP per capita: $2,200 (compared to $48,000 in the U.S.)

- Currency: Ouguiya

Politics

- Government: Republic (currently under military rule)

- Legal system: Mix of Islamic and French civil law

- President: Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz

- Recent history: Gained independence from France in 1960. Aziz came to power in a military coup in 2008, overthrowing first democratically elected leader. Aziz was elected in 2009 as a way to validate his rule.

Sources: United Nations, Encyclopedia Britannica, CIA World Factbook, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, "Disposable People," BBC Country Profiles

Nouakchott, Mauritania (CNN)

Moulkheir Mint Yarba returned from a day of tending her master’s goats out on the Sahara Desert to find something unimaginable: Her baby girl, barely old enough to crawl, had been left outdoors to die.

The usually stoic mother — whose jet-black eyes and cardboard hands carry decades of sadness — wept when she saw her child’s lifeless face, eyes open and covered in ants, resting in the orange sands of the Mauritanian desert. The master who raped Moulkheir to produce the child wanted to punish his slave. He told her she would work faster without the child on her back.

Trying to pull herself together, Moulkheir asked if she could take a break to give her daughter a proper burial. Her master’s reply: Get back to work.

“Her soul is a dog’s soul,” she recalls him saying.

Later that day, at the cemetery, “We dug a shallow grave and buried her in her clothes, without washing her or giving her burial rites.”

“I only had my tears to console me,” she would later tell anti-slavery activists, according to a written testimony. “I cried a lot for my daughter and for the situation I was in. Instead of understanding, they ordered me to shut up. Otherwise, they would make things worse for me — so bad that I wouldn’t be able to endure it.”

Moulkheir told her story to CNN in December, when a reporter and videographer visited Mauritania — a vast, bone-dry nation on the western fringe of the Sahara — to document slavery in the place where the practice is arguably more common, more readily accepted and more intractable than anywhere else on Earth.

An estimated 10% to 20% of Mauritania’s 3.4 million people are enslaved — in “real slavery,” according to the United Nations’ special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, Gulnara Shahinian. If that’s not unbelievable enough, consider that Mauritania was the last country in the world to abolish slavery. That happened in 1981, nearly 120 years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States. It wasn’t until five years ago, in 2007, that Mauritania passed a law that criminalized the act of owning another person. So far, only one case has been successfully prosecuted.

The country is slavery’s last stronghold.

Even knowing those facts before we departed, what we found on the ground in West Africa astonished us. Mauritania feels stuck in time in ways both quaint and sinister. It’s a place where camels and goats roam the streets alongside dented French sedans; where silky sand dunes give the land the look of a meringue pie topping; where desert winds play with the cloaks of nomadic herdsmen, making their silhouettes look like dancing flames on the horizon; and where, incredibly, the nuances of a person’s skin color and family history determine whether he or she will be free or enslaved.

That reality permeates every aspect of Mauritanian life — from the dark-skinned boys who serve mint-flavored tea at restaurants to the clothes people wear. A man wearing a powder-blue garment that billows at the arms and has fancy gold embroidery on the chest is almost certainly free and comes from the traditional slave-owning class of White Moors, who are lighter-skinned Arabs. A woman in a loud tie-dye print that covers her hair, but not her arms, is likely a slave. Her arms are exposed, against custom, so she can work.

It’s a maddening, complicated place — one made all the more difficult for outsiders to understand because no one is allowed to talk about slavery. When we confronted the country’s minister of rural development about slavery’s existence, Brahim Ould M’Bareck Ould Med El Moctar told us his country is among the freest in the world. “All people are free in Mauritania and this phenomenon (of slavery) no longer exists,” he said.

The issue is so sensitive here that we had to conduct most of our interviews in secret, often in the middle of the night and in covert locations. The only other option was to do them in the presence of a government minder, who was assigned to our group by the Ministry of Communications to ensure we didn’t mention the topic. Our official reason for entering the country was to report on the science of locust swarms; our contacts for that story were unaware of our plan to research slavery.

If we were caught talking with an escaped slave like Moulkheir, we could have been arrested or thrown out of the country without our notebooks and footage. That point was made clear to us in a meeting with the national director of audiovisual communications, Mohamed Yahya Ould Haye, who told us journalists who attempted to report on such topics were jailed or ejected from the country.

More important, getting caught talking about slavery could have put our sources at risk. Anti-slavery activists say they have been arrested and tortured for their work.

When we met Moulkheir in a gray, open-air office in Nouakchott, Mauritania’s seaside capital city where concrete buildings are scattered on the Sahara like Legos in a sandbox, our hired security guard stood watch at the door to make sure no government representatives were following us, as they had during other parts of our visit.

Moulkheir, who is in her 40s, wore a bright blue headscarf and matching dress. She was brave enough to tell her tale with poise and unflinching resolve. She did so in hopes her former masters would be brought to justice. She was aware that telling her story could put her in danger but asked to be named and to have her photograph shown. “I am not afraid of anyone,” she said.

As she recounted her torture, imprisonment and escape, her hands gestured wildly but her eyes stayed focused, with dart-like precision, on mine.

Listening to her story, two facts became painfully clear:

In Mauritania, the shackles of slavery are mental as well as physical.

And breaking them — an unthinkably long process — requires unlikely allies.

DOCUMENTARY: The long path to freedom

Moulkheir was born a slave in the northern deserts of Mauritania, where the sand dunes are pocked with thorny acacia trees. As a child, she talked more frequently with camels than people, spending days at a time in the Sahara, tending to her master’s herd. She rose before dawn and toiled into the night, pounding millet to make food, milking livestock, cleaning and doing laundry. She never was paid for her work. “I was like an animal living with animals,” she said.

Slave masters in Mauritania exercise full ownership over their slaves. They can send them away at will, and it’s common for a master to give away a young slave as a wedding present. This practice tears families apart; Moulkheir never knew her mother and barely knew her father.

Most slave families in Mauritania consist of dark-skinned people whose ancestors were captured by lighter-skinned Arab Berbers centuries ago. Slaves typically are not bought and sold — only given as gifts, and bound for life. Their offspring automatically become slaves, too.

All of Moulkheir’s children were born into slavery.

And all were the result of rape by her master.

The attacks began when she had barely begun to cover her head with a scarf, a Muslim tradition that begins at puberty. The master took Moulkheir out to the goat fields near his home and raped her in front of the animals. Moulkheir had no choice but to endure this torture. She’d convinced herself that her master knew what was best for her — that this was the way it had always been, would always be.

She couldn’t see beyond her small, enslaved world.

To document slavery in Mauritania, we traveled out of Nouakchott and into the Sahara, where the desert landscape is so expansive it’s claustrophobic.

We drove for hours without seeing a single person or dwelling, save for the military checkpoints where men in black turbans — only slivers of their faces showing — stop every vehicle, demanding to know what its occupants are doing in the desert.

“I was like an animal living with animals.” — Moulkheir Mint Yarba, escaped slave

The scenery is a highlight reel of emptiness: dusty plains, thorny shrubs and sand dunes flying past our Land Cruiser’s windows at 75 mph. It looks as if an enormous syringe has been jabbed into the ground to suck out all the color — except for yellows and browns.

The farther into the desert one goes, the more it seems possible that the outside world simply doesn’t exist — that memory is playing a trick. That this is all there is.

It’s in this isolated environment that slavery has been able to thrive.

Occasionally, a village pops into view. In most of these, we saw the same scene: dark-skinned people working as servants. They live in tents made of rags, some so shabby that their bark-stripped stick frames look like carcasses left to rot in the sun.

It’s impossible, from the road, to know for sure which of these men and women are enslaved and which are paid for their work. Many exist somewhere on the continuum between slavery and freedom. Some are beaten; some aren’t. Some are held captive under the threat of violence. Others are like Moulkheir once was — chained by more complicated methods, tricked into believing that their darker skin makes them less worthy, that it’s their place to serve light-skinned masters. Some have escaped and live in fear they’ll be found and returned to the families that own them; some return voluntarily, unable to survive without assistance.

Because slavery is so common in Mauritania, the experience of being a slave there is quite varied, said Kevin Bales, president of the group Free the Slaves. “We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people,” he said when asked about how slaves are usually treated in Mauritania. “The answer is all of the above.”

In a strange twist, some masters who no longer need a slave’s help send the servants away to slave-only villages in the countryside. They check on them only occasionally or employ informants who make sure the slaves tend to the land and don’t leave it.

Fences that surround these circular villages are often made of long twigs, stuck vertically into the ground so that they look like the horns of enormous bulls submerged in the sand.

Nothing ties these skeletal posts together. Nothing stops people from running.

But they rarely do.

Life in Mauritania

To understand Moulkheir’s path to freedom, we sought out the two unlikely allies who helped liberate her in 2010: a slave and a slave master.

Boubacar Messaoud and Abdel Nasser Ould Ethmane grew up in radically different worlds. Each would take an amazing journey of his own to end up fighting for the freedom of Moulkheir and others like her.

We met Abdel, an olive-skinned man with a marathon-runner’s figure and a Caesar-style haircut, in his family’s apartment in Nouakchott, well past dark, while our government minders were asleep. Abdel’s oversized blue robe, a sign of nobility, crinkled like crepe paper as he tucked the flowing garment behind his knees and sat down on an embroidered green sofa. He offered us camel’s milk and asked if he could smoke before curling into the couch like a Cheshire cat and beginning his story.

It’s the tale of how a slave owner becomes an abolitionist.

Abdel is 47. He was 7 when he selected a boy with skin the color of coal to be his personal slave for life. The young slave owner made the choice at his circumcision ceremony; he could have picked anything as a gift for this rite of passage into adulthood: a goat, candy, money. But Abdel wanted the dark-skinned boy.

Abdel Nasser Ould Ethmane got his first slave when he was 7. "It was as if I were picking out a toy." At 16, he set his slaves free. Today, Abdel is one of Mauritania's leading abolitionists.

Ethnic groups in Mauritania

White Moors

Lighter-skinned Berber people who speak Arabic and have traditionally owned slaves. Most men wear light blue shirts called boubous, which have ornate designs on the chest. White Moors are the power class in Mauritania and control more wealth than any other group. Some, however, live in poverty. It's not uncommon to find a White Moor living in a tent only slightly larger than that of his or her slaves.

Black Moors

Darker-skinned people who historically have been enslaved by the White Moors. Originally from sub-Saharan Africa, the Black Moors have taken on many aspects of the Arab culture of their masters. They speak Hassaniya, an Arabic dialect.

Black Africans

Mauritania‘s other darker-skinned people come from several ethnic groups, including the Pulaar, Soninke and Wolof. These groups also are found in Senegal, which shares Mauritania‘s southern border. They look similar to Black Moors, but never were enslaved and are quite different in terms of culture and language.

Haratine

The word literally means "freed slaves," but it can be used to describe people who are in slavery or who belong to the former slave class of Black Moors. Many Haratine people exist somewhere on the spectrum between slavery and freedom and are the target of class- and race-based discrimination.

“It was as if I were picking out a toy,” Abdel said of choosing his slave. “For me, it was as if he were a thing — a thing that pleased me. This idea came to me because there were all these stories about him which made me laugh — that he talked in his sleep, that he was a bit chubby and a bit clumsy, that he was always losing the animals he was supposed to be watching over and was then always getting punished for this.

“So for me, he was an interesting and comic figure. It’s normal that I chose him.”

Abdel was careful to say his family never beat his slave, Yebawa Ould Keihel. Family members did, however, force him to tend their herds of goats and camels, out in the deserts of central Mauritania, without pay. At the time, Abdel told us, he didn’t feel guilty. In fact, he and the other children in their nomadic group, which followed water from one anonymous area of the Sahara to the next, openly taunted the slaves who served them. When it rained on the Tagant plateau, slaves like Yebawa had to hold up the edges of the master-family’s tent to prevent water from leaking in, he told us. Abdel recalls hearing the slaves’ teeth chattering through the cold desert nights — and mocking this “teeth music” with his slave-owning friends.

“Here they were standing up, protecting us, and we were completely unconscious (and) ignorant,” Abdel said. “This was actually quite innocent because, for us, slavery was really a natural state. One must really have in mind that when one is born into a certain environment, it is considered the right one — just and fair.”

Abdel could have gone on thinking that way if it weren’t for a teacher who sent him to a library where books transported him to other worlds — places where slavery had long been abolished.

Abdel’s parents wanted him to go to school in Nouakchott, 300 miles to the west of the sandy plateau where they raised goats and camels. He was assigned a tutor, an eccentric European man with chunky glasses and an Afro, as Abdel recalls. The man required Abdel, at about 12, to go to Nouakchott’s French Cultural Center every day to do extra reading.

Hesitant at first, Abdel soon dove into every book he could find. He started with French comic books like “Asterix.” It wasn’t long before he was picking up volumes about the French Revolution.

In a book on the subject of human rights, pulled from the library’s shelves almost at random, Abdel found the idea that would alter his life forever:

Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.

Abdel read the line again and again.

“I started to ask myself if lies were coming out of this book,” he told us, “or if they were rather coming out of my very own culture.”

Once this seed — a question that would undo his entire world — had been planted in his mind, he couldn’t stop it from growing. By 16, he returned to his family’s nomadic settlement in the desert to tell his slaves that they were free. He was shocked by their response.

They did not want to be free, he recalled. Or they didn’t know what freedom was.

His mother told him to stop being silly — that the slaves needed the family to take care of them and that this was the natural order of the world, the way it always would be.

But Abdel was becoming ever more set in his belief that slavery was wrong — that the rights of his slave, Yebawa, were no different from his own.

In his early 20s, Abdel organized a community of young activists, most of them light-skinned like him, who began to debate the merits of the slavery they’d grown up with and had, in fact, perpetuated. They sat on sand dunes late at night — in secret, for fear they would be found out by the government, which officially abolished slavery in 1981 but allowed it to continue. There, they discussed ways to end the practice that was so ingrained in their culture.

It was through these conversations that Abdel met Boubacar Messaoud.

The men came together on a rooftop in 1995, under a midnight sky of desert stars. In muffled voices, they plotted the founding of the abolitionist organization called SOS Slaves. It’s one of the few groups fighting slavery in Mauritania today.

And it would liberate Moulkheir.

Bouboucar Messaoud, the son of slaves and co-founder of an abolition group, says slavery is engrained in Mauritania. "If a slave becomes free, others will judge him as evil. The society he belongs to does not accept, nor forgive, him for being free."

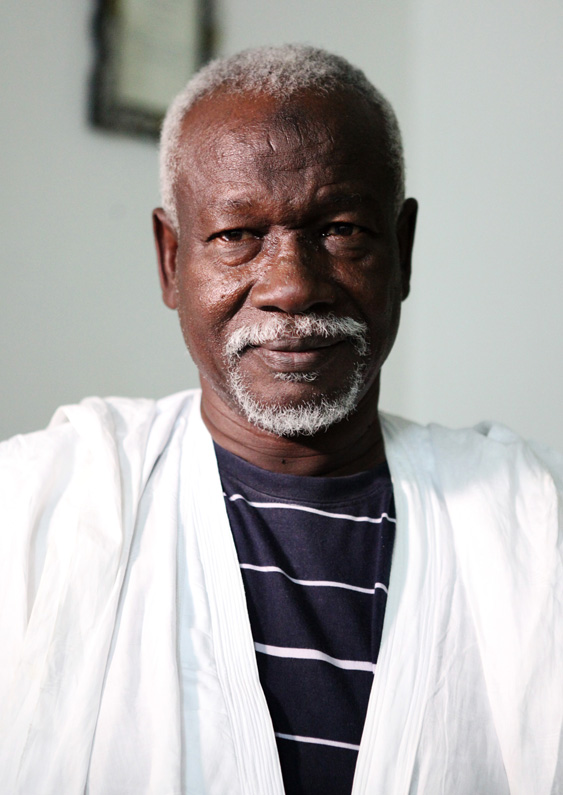

Boubacar still lives in the concrete compound that served as the meeting place for that first rooftop discussion about SOS Slaves. The night we interviewed him, we walked a circuitous route to his house, turning down sandy alleys and doubling back to check for followers. We slipped through the metal door that serves as the compound’s entry around midnight, with only a sliver of the moon hanging in a charcoal sky. We found Boubacar, an imposing figure with strong shoulders, ebony skin and a snowy goatee, reclining in his living room.

Why slavery still exists in 2012

Why has slavery continued in Mauritania long after it was abolished elsewhere? There are many factors that contribute to the complex situation. Here are a few:

Politics

Mauritania's government has done little to combat slavery and in interviews with CNN denied that the practice exists. "All people are free in Mauritania and this phenomenon (of slavery) no longer exists," one official said.

Geography

Mauritania is a huge and largely empty country in the Sahara Desert. This makes it difficult to enforce any laws, including those against slavery. A branch of al Qaeda has found it an attractive hiding place, and the country's vastness also means that rural and nomadic slave owners are largely hidden from view.

Poverty

Forty-four percent of Mauritanians live on less than $2 per day. Slave owners and their slaves are often extremely poor, uneducated and illiterate. This makes seeking a life outside slavery extremely difficult or impossible. On the other hand, poverty has also led to some slave masters setting their slaves free, because they can no longer afford to keep them.

Religion

Local Islamic leaders, called imams, historically have spoken in favor of slavery. Activists say the practice continues in some mosques, particularly in rural areas. Various religions in many countries have been used to justify the continuation of slavery. "They make people believe that going to paradise depends on their submission," one Mauritanian activist, Boubacar Messaoud, said of how religious leaders handle slavery.

Racism

Slavery in Mauritania is not entirely based on race, but lighter-skinned people historically have owned people with darker skin, and racism in the country is rampant, according to local analysts. Mauritanians live by a rigid caste system, with the slave class at the bottom.

Education

Perhaps most surprising, many slaves in Mauritania don't understand that they are enslaved; they have been brainwashed, activists say, to believe it is their place in the world to work as slaves, without pay, and without rights to their children. Others fear they would lose social status if they were to run away from a master who is seen as wealthy. Slaves of noble families attain a certain level of status by association.

An evening breeze sailed through the open windows as he told us about his life as the son of slaves in southern Mauritania, near the country’s border with Senegal. Even though the master had granted his family limited freedom before Boubacar was born, he still grew up working in the man’s field, he said, and the master took a cut of the crops they produced each year. This may not have been literal slavery, but it wasn’t substantially different. “In that period, I could still feel that I was a slave,” Boubacar told us, “that I was different from other children.”

One important distinction: He could not go to school.

The master would not allow it, and his parents weren’t going to take up the issue. This is something Boubacar never understood. So at 7, the same age Abdel selected his slave, Boubacar went to the local school even though he wasn’t allowed to be there. An administrator saw him standing on the steps of the schoolhouse crying and, out of empathy, Boubacar told us, allowed him to attend.

Education would change Boubacar’s life, just as it had changed Abdel’s. Once he started reading about life outside his tiny world, he grew dedicated to the idea that all people — including those in his family — should be free.

Years later, he would find an instant ally in Abdel, the former slave master. This collaboration — between two men from opposite ends of Mauritania’s rigid caste system — would become the inherent power of SOS Slaves.

“If we fail to convince a maximum number of whites and a maximum number of blacks” that slavery is wrong, Boubacar told us, “then slavery will not go away.”

Together, they developed a method for fighting slavery in Mauritania.

Step one was to interview escaped slaves and publicize their stories. The thinking: If a person knows slavery exists, how could they not want to fight it?

Step two was to help slaves gain their freedom. This was trickier, Boubacar told us, because a slave like Moulkheir — the woman whose child was left outside to die — must decide she wants to be free before SOS can do anything to help.

Scholars find many similarities between modern Mauritanian slavery and that in the United States before the Civil War of the 1800s. But one fundamental difference is this: Slaves in this African nation usually are not held by physical restraints.

“Chains are for the slave who has just become a slave, who has . . . just been brought across the Atlantic,” Boubacar said. “But the multigeneration slave, the slave descending from many generations, he is a slave even in his own head. And he is totally submissive. He is ready to sacrifice himself, even, for his master. And, unfortunately, it’s this type of slavery that we have today” — the slavery “American plantation owners dreamed of.”

For a slave to be free, she first must break the shackles in her mind.

The first time activists tried to rescue Moulkheir, she refused to go.

She’d never known life outside of the desert. The thought of the city scared her and she feared violent retribution by masters who had already been so abusive.

“She was unwilling to talk to us — with anyone, for that matter,” said Boubacar, the SOS Slaves co-founder. “She was with her masters and that was that.”

This was 2007, shortly before Mauritania passed a law criminalizing slavery. After that law went into effect, the government embarked on a campaign to prove slavery did not exist, Boubacar said. A public official in Adrar, the region where Moulkheir lived, tried to deny the presence of slavery in his province. An SOS Slaves representative in that region said otherwise: We know of a slave named Moulkheir, he told officials. She is very badly treated. We tried to rescue her but she would not come with us. She needs help.

To ensure that Moulkheir’s story of slavery would not be made public, Boubacar and Moulkheir said, government officials staged a fake rescue. They arrived in a police car and took the woman and her five children away from the master who had enslaved all of them since birth. The master cooperated, Moulkheir said. To her surprise and confusion, he gave her six goats and a loincloth to take with her. She’d never had a possession before.

“I realized later that this was all in order to conceal my true condition of slavery,” she told anti-slavery activists, according to a written transcript of the interview.

Her taste of freedom would be brief, like an ethereal mirage on the horizon.

Soon, Moulkheir and her children were given to a former colonel in the Mauritanian army, SOS Slaves says. He was supposed to employ them. What he did, Moulkheir says, is re-enslave them.

“He turned out to be worse” than the original master, Moulkheir told us. “He beat me and slept with my daughters. He would fire above their heads with a gun” to scare them.

Soon, the abuse — directed not just at her, but at her young children — would be more than Moulkheir could stand.

Slave villages, and life in limbo

The fact that Moulkheir can talk about the abuses she suffered is, in itself, a victory. For many slaves, the idea of being owned by another person and treated as a piece of livestock is normal — and has been for centuries.

Against the government’s wishes, a small number of reporters and activists have visited Mauritania to try to document this phenomenon, which is unique in the modern world. In the 1990s, Kevin Bales, the American anti-slavery activist, posed as a zoologist to obtain permission to enter the country, which is required of most outsiders. He found a system of slavery that echoes that of Old Testament times.

“Its closeness to old slavery makes the situation in Mauritania highly resistant to change. Because it never went away or reappeared in a new form, this slavery has a deep cultural acceptance,” he wrote in the book “Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy.” “Many people in Mauritania see it as a natural and normal part of life, not as an aberration or even a real problem; instead, it is the right and ancient order of things.”

Our first journey out of Nouakchott took us north, where purple mountains dip in and out of the desert like a dragon crawling through the sand. We would visit a center for locust research located in that part of the country. The true goal, of course, was to find people who were currently enslaved.

A government minder was assigned to shadow us, which would make it difficult to talk with slaves at length. We drove in a small convoy, our SUV behind the government’s white 4x4 truck. In a remote stretch of the Inchiri region, rectangular tents made of bright-colored rags caught our eyes. We waited for the government’s vehicle to shrink on the horizon ahead, then slammed on the brakes and pulled over to talk to a group of villagers living by the side of the road. Before the government officials noticed, we were able to speak with slaves and slave masters.

Some people live in “slave villages” without their masters. Still, they may be forced to work without pay, and the land usually is owned by a master. Residents live in extreme poverty.

Some people live in “slave villages” without their masters. Still, they may be forced to work without pay, and the land usually is owned by a master. Residents live in extreme poverty.

They talked about their situation as if nothing were wrong.

Fatimetou, a dark-skinned woman who covered her hair with a purple-and-green fabric that would look at home at a Grateful Dead concert, told us her family doesn’t own anything and can’t leave the village.

“On this land, everybody is exploited,” said another dark-skinned man, speaking through a translator.

We ducked into the shade of a tent to muffle the sound of our potentially dangerous conversation. Within eyeshot was another tent camp, slightly larger. There, we met a man who appeared to be Fatimetou’s master.

Mohammed, an older man with a toothy smile and slightly lighter skin, told us in a nonchalant manner that he holds workers on the compound without compensation.

“We don’t pay them,” he said through a translator. “They are part of the land.”

Four sets of eyes peeked through the sheets of the slave master’s tent while we talked. They disappeared before our minder returned to shut down the interview and warn us against stopping in the desert without seeking his consent. We asked a few questions about locusts as he approached to try to keep up our cover, but sensed he was getting angrier.

We apologized halfheartedly and moved on, wishing we’d had more time to talk with people who see slavery as a normal part of life.

After the tour of the north, we turned our sights south to the Brakna region, where the terrain is the color of Mars. Our mission was to visit the villages inhabited entirely by slaves and former slaves, places called adwaba.

These villages, more than anywhere else, represent the limbo that many slaves find themselves in. Neither free nor shackled, the residents of adwaba villages are owned and beholden to masters who live elsewhere, according to abolitionists. The slaves’ owners come to town for harvest, to reap the bounty of the workers they do not pay. It’s as if these slaves are bound to their masters by a long leash — one that’s elastic but can’t be broken.

At the first slave village, we tried the same trick to ditch our minders — stopping unexpectedly and then rushing to do interviews before they could make a U-turn and come back.

At the base of a picturesque sand dune, where goats nibbled on bits of shrubs, we found Mahmoud, a dark-skinned 28-year-old man wearing a purple striped shirt and a black turban. Kids clamored at our ankles as Mahmoud gave us a hurried tour of his village. It’s unclear who owns the land here, but in many adwaba villages like this one, all profits are said to go back to the “tribe.” (According to local slavery experts, one light-skinned family usually manages the tribe of black slaves).

Food shortages in Mahmoud’s village are so dire that children stave off hunger pangs by eating sand. We saw one barefoot boy scooping the gritty earth into his mouth with a bright green piece of plastic.

Such conditions are yet another reason some Mauritanian slaves actually prefer to stay in the homes of their masters: If they leave, it’s difficult to survive.

Couple all of this with masters — and some local religious leaders, according to activists — who tell slaves and the general population that their natural place in society is serving their masters, and you have a recipe for slavery that persists in 2012.

“If a slave becomes free, others will judge him as evil,” Boubacar had told us. “The society he belongs to does not accept, nor forgive, him for being free.”

Moulkheir Mint Yarba and her daughter, Selek'ha, were beaten and raped by their masters. Only after they each suffered something unimaginable were they able to break slavery's mental shackles and seek their freedom.

Moulkheir Mint Yarba and her daughter, Selek'ha, were beaten and raped by their masters. Only after they each suffered something unimaginable were they able to break slavery's mental shackles and seek their freedom.

Moulkheir’s oldest child, Selek’ha Mint Hamane, has skin the color of milky coffee — a visual reminder that she was born of her black mother’s rape by her first, light-skinned master.

Slavery's history in Mauritania

Circa 200 to 1900s

Arab slave traders in the region that would become Mauritania capture darker-skinned people from sub-Saharan Africa and force them to work without pay. "You can trace this back for 2,000 years," said Kevin Bales, CEO of Free the Slaves.

1905

The colonial French administration declares an end to slavery in Mauritania. The abolition never takes hold, however, in part because of the vastness of the country.

1948

The United Nations adopts The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which abolishes slavery internationally.

1961

After gaining independence from France the year before, Mauritania adopts a new constitution abolishing slavery. The effort has little impact, according to written accounts.

1980 - 1981

Mauritania's government abolishes slavery and declares that it no longer exists. This abolition was "essentially a public-relations exercise," says Human Rights Watch. "True, the government abolished slavery," writes Bales, the American anti-slavery activist, "but no one bothered to tell the slaves about it."

1995

A former slave and a former slave owner start an anti-slavery organization called SOS Slaves.

2007

Mauritania passes a law criminalizing slavery. It allows for a maximum prison sentence of 10 years. To date, only one legal case against a slave owner has been successfully prosecuted.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica; Human Rights Watch; UN.org; Lonely Planet; "Disposable People: New slavery in the global economy"; Library of Congress; BBC

Cruelty would drip from one generation to the next.

Selek’ha’s beatings by the new master, the former colonel, started by age 13. The rapes came soon after. He would enter her room in the middle of the night, she said, waking her suddenly by smacking her face with an electrical cord or hitting her back with a stick.

In spite of this treatment, Selek’ha still considered this light-skinned man to be a benevolent relative. He forced her to do chores all day long and beat and raped her in the middle of the night. He also made sure she was fed in a country where many die of hunger.

“When I was with them, I thought they were family,” Selek’ha told us in an interview held in the middle of the night, so as not to draw attention. “But when they began to beat me and they did not beat their other sons and daughters, I realized something was wrong.”

One incident forever changed her psyche and led Selek’ha and her mother, Moulkheir, to plot their escape: In 2009, when Selek’ha was 15 or 16, her master raped and impregnated her.

From the moment she realized she was pregnant, Selek’ha was terrified of the day the child would be born. The master would be furious, she knew.

That child’s birthday would never come. In Selek’ha’s ninth month of pregnancy, her master put her in the back of a pickup truck and drove her down a bumpy rural road at high speeds, jostling Selek’ha and her unborn child like laundry in a washing machine.

Selek’ha’s baby died on that ride — just as the master planned.

“There are no bad things they did not do to me,” she said. “He killed my baby.”

Just as another master had killed her mother’s.

Moulkheir felt a new pain, unlike anything she’d experienced before.

She wanted out.

Look closely at the desert of Mauritania and you’ll see that winds carry ghosts of sand along the surface of the ground, slowly pushing massive dunes across the Sahara.

Freedom, too, is a transformative force here, but barely visible.

During our travels, we met people who never knew freedom existed; people who claimed they were not slaves but whose environments suggested otherwise; people who dreamed about freedom but were too scared to escape; people who had seen friends die trying.

Late at night, we spoke with Yebawa Ould Keihel, the slave Abdel selected at his circumcision ceremony decades ago.

We met Yebawa in our hotel room, shades drawn — again, with a security guard keeping watch in the lobby in case someone had followed him.

Yebawa has skin that evokes an African sky at midnight. He wore a thick white scarf and a blue cloak that gave him the air of a judge.

Abdel, the SOS co-founder, said he freed Yebawa decades ago. He is in his early 40s now works as a servant for Abdel’s family, and others, for pay. But when we asked Yebawa about the moment he was freed, he was confused by the idea. It seemed as though he’d never considered it before.

“No one ever told me I was free. I don't know what that would be like,” he said through our local translator, who, after the interview, expressed shock to have heard those words come out of the mouth of a person today, even in Mauritania.

“I guess it would be something like what I am doing now, getting paid for work.”

Abdel would later tell us he considers Yebawa’s plight to be one of his greatest failures. He has dedicated his life to working against slavery in Mauritania. But the very man he enslaved and then liberated hasn’t been able to capitalize upon his freedom — or, it seems, doesn’t understand it.

“It is a catastrophe,” Abdel told us. “He’s my slave — he’d say nothing different even today. So, with Yebawa, I failed. I had success with others, but not with Yebawa.”

We asked if there was a chance Yebawa’s life still could change.

“No, it is too late,” he said. “Since he was little he’s been with animals, watching the herds, until now. The only difference is that now he gets a salary. . . . A person like Yebawa — if he gets paid a salary — he can’t count to see if he was paid right or not.”

Boubacar, the other SOS founder, later would tell us that when masters grant freedom to their slaves, in a perverse way they are actually serving to further enslave them. “Freedom is not granted,” he said. “When freedom is granted by the master you remain dependent, grateful.”

Freedom is something that must be claimed.

From slave to free — and in-between

News that Moulkheir had changed her mind — that she now wanted out of slavery — traveled from her master’s compound to the office of SOS Slaves in Nouakchott.

Moulkheir’s brother alerted SOS Slaves to her situation. His sister had not been set free, he told Boubacar, the SOS co-founder. She had been recaptured and now was being treated even worse. If they went back to rescue her, he said, Moulkheir would be willing to leave. Boubacar agreed to help. This, after all, is why he and Abdel had founded SOS Slaves: to liberate people like Moulkheir, who had decided that they wanted to claim their freedom.

To escape, however, she would have to leave her children behind.

While the second master was out of town, an SOS representative in that region of the desert went to the compound where Moulkheir had been held for nearly three years and drove her to freedom. Later, she would go back to confront her master and demand custody of her children.

He gave her four of the five. He kept Selek’ha.

“No one ever told me I was free. I don't know what that would be like.” — Yebawa Ould Keihel, a slave freed by his master

Moulkheir had one foot in the free world. The other remained firmly planted in the northern deserts of Mauritania, where her daughter was still enslaved. SOS could facilitate Selek’ha’s escape. But first they would have to convince her that she needed to go. SOS arranged a phone call between mother and daughter.

Moulkheir told her daughter that she had to stand up for her freedom.

When the master went away to a nearby village, SOS sent a team to rescue Selek’ha. Reunited in the city, mother and daughter are now focused on prosecuting the two slave owners who worked them all their lives without pay.

“I demand justice — justice for my daughter that they killed, and justice for all the time they spent beating and abusing me,” Moulkheir told us, her eyes more serious than ever. “I want justice for all the work I did for them. I hold them all responsible.”

Her odds of success in court are not good.

Activists have tried to bring dozens of cases to trial since 2007, when the law criminalizing slavery was passed. Only one has been successful. In January 2011, Oumoulmoumnine Mint Bakar Vall was sentenced to six months in prison for enslaving two young girls, according to news reports. Yet the victory was seen as bittersweet: Anti-slavery activists were arrested and sentenced to 6 months in prison for bringing the case to the attention of the government, according to the human rights group Anti-Slavery International.

In other instances, activists have gone on hunger strikes to try to force prosecutions.

So far, no judge has taken up Moulkheir’s case.

Moulkheir and Selek’ha, now 18, live together in a one-room shack on the outskirts of Nouakchott. The dwelling has a corrugated metal roof and no furniture. They sleep on the floor with sheets and, on winter nights, the warmth of their family.

It’s a simple existence, but one that is peaceful and, most importantly, dictated by what the mother and daughter want to do with their time, not what someone else demands.

Asked what she likes best about freedom, Moulkheir said: “I can make tea when I want. I can sleep. In the past, I could not sleep. I was like a donkey — just working.”

Two or three times a week, the two attend a school for escaped slaves and their children. It’s a new project of SOS Slaves, located in a neighborhood where goats walk the dusty streets and men ride rickety wooden donkey carts, smacking the animals with switches to keep them moving down the alleys.

We visited the center quickly, for only 20 minutes, because we didn’t want to be seen in a place that would give away our cover. To avoid being followed, we arrived in one car and left in another.

From the outside, the school is eerily silent and still. But the anonymous facade gives way to a warm interior. The walls are painted a Caribbean turquoise and floors are speckled with red, yellow and blue chips of tile, the kind that might be found in a Tex-Mex restaurant in the United States. Women’s voices echo in an interior courtyard. The chatter of sewing machines is contained within the school’s concrete walls — a secret to the outside world.

Here, former slaves and their children learn skills that will help them in their new lives, post-slavery. In one room, Mariem, 21, braids the hair of a mannequin that’s wearing oversized, Bono-style sunglasses. Someday, she says, she’d like to open her own hair salon. In another room, a dozen women sit on the ground tie-dying bright-colored garments.

Moulkheir is with them, weaving white threads into a dress.

Alioune Ould Bekaye, director of the recently opened center, says education is the only way former slaves can make a life for themselves as freed people.

“It’s another way to liberate them,” he said.

So far, 30 women have enrolled at the center, he said, with funding coming from SOS Slaves and the European Union. Much more is needed to meet the country’s demand for training of former slaves. Only one other such center exists, also in Nouakchott. There’s no help for slaves in rural areas, and many thousands of former slaves live on the fringes of the capital city in abject poverty. Slaves who don’t receive training are at more risk of being re-enslaved.

Selek’ha says the center is changing her life.

During our afternoon visit, while the Saharan sun beat down on the city outside, she sat in the shade at a sewing machine, stitching pink thread into khaki material — the start of a pair of trousers she was making from a pattern. “I want to know how to sew, and then I want to get my own sewing machine,” she told us. “Eventually, I want to open a shop.”

Sometimes she wakes up in the middle of the night thinking of the master who beat her, raped her and killed her unborn baby. None of those thoughts come to her when she’s moving her hands across the fabric — creating something new.

Photos: School for escaped slaves

On our final evening in Mauritania, we met one last time with Moulkheir and Selek’ha, in a private residence with the exterior lights turned off.

As we took the women through yet another conversation about their lives under the hand of the masters who beat and raped them, Moulkheir grew visibly uncomfortable. She covered her mouth with green fabric and put sunglasses over her eyes — a pair with fake rhinestones on the frames. “I can’t talk about this anymore,” she said.

Her daughter urged her to continue. Speaking out might help their case against the masters, she said, because outsiders will then know what is happening here, largely hidden from view and in silence. But Moulkheir wouldn’t budge.

I asked them one final question: What did their master look like? I wanted to be able to describe to readers the face that had haunted them over the years and caused them so much pain.

“It's a destitute country. It needs a few friends in the world.” — Kevin Bales, Free the Slaves

“He was light-skinned with a beard and glasses,” Selek’ha said.

There was a pause. Then our translator spoke, giving words to the elephant in the room:

“He looked like you.”

I know it’s irrational, but in that moment I felt responsible for everything that had happened to Moulkheir and Selek’ha — and to their children who died.

Who was I to ask them to unearth the horrors from their past? What could people outside this troubled country do to end a practice that’s thousands of years old and so ingrained in the national psyche?

As we wrapped up the interview, I thought back to something Moulkheir had told us earlier in the week. I’d asked what she would say to people in the U.S., many of whom aren’t aware that slavery still exists in Mauritania — or who might feel helpless after learning about it.

Her reply was simple: “I would ask them to help us to change our country.”

But how?

It’s a question that keeps me up at night.

Activists say the international community has done relatively little to pressure Mauritania to address slavery. “The French government and American government have had a lot of opportunities to help Mauritania step up and deal with this — and have pretty much squandered those opportunities,” says Kevin Bales, of Free the Slaves. People tend to focus on topics like child trafficking and sex slavery, says Sarah Mathewson, Africa program coordinator at Anti-Slavery International, rather than the old-world slavery in Mauritania.

The U.S. ambassador to Mauritania, Jo Ellen Powell, called slavery in the country "completely unacceptable and abhorrent" and said America is pressuring Mauritania to change. The nation should invest in the education of its children rather than "keeping them sweeping floors somewhere or herding goats," she said. "Human capital development is something that's very important to the Mauritanians and I hope that they get that connection."

For a few weeks after returning home, I tried to block the most troubling images from my mind: haunting villages where kids eat sand; a slave owner who smiled while he told us about the free labor he gets from people with darker skin; and, most of all, the piercing eyes of a woman whose master left her infant in the sand to die.

Mauritania is a place of agonizing beauty, one that’s hard not to love and curse. Its people have lived with unfulfilled potential and broken promises for decades, since the country first tried to abolish slavery in 1905. But that could change, several activists told us, if Mauritania knew the rest of the world was watching.

The United Nations has proposed a number of changes the Mauritanian government could make to quicken the end of slavery. Among them: Pay lawyers to represent victims; allow international monitors into the country to conduct a full survey of slavery; and fund centers like the one SOS runs to rehabilitate slaves who have claimed their freedom.

It would help if a global public demanded these changes. “It’s a destitute country,” says Kevin Bales. “It needs a few friends in the world.”

Perhaps then women like Moulkheir and Selek’ha could find justice.

And Boubacar and Abdel could get their wish.

We asked the SOS founders how they will know when their fight against slavery in Mauritania is over — how they’ll know they have won. Both men had the same answer:

When a former slave becomes president.

"Help us to change our country"

Related stories

- When freedom is 4,000 miles away

- Slave master becomes an abolitionist

- UN: There is hope for Mauritania

- Official: Slavery does not exist here

- Ambassador: Slavery is ‘abhorrent’

- EU: End slavery ‘not only in law but in practice’

- Mauritanian refugees find new home in Ohio

- How to help end slavery in Mauritania

- iReport: Send a message of hope

- Gallery: A place where slavery is the norm

How This story was reported

CNN's John D. Sutter and Edythe McNamee traveled to Mauritania for eight days in December 2011 to witness slavery first-hand. Scenes of Moulkheir Mint Yarba's escape from slavery are reconstructed based on interviews with those involved, written and video testimonies given to abolitionists at the time of her escape and legal documents provided by SOS Slaves. CNN could not confront the men who allegedly enslaved Moulkheir. Their names have been omitted for this reason. Most interviews were conducted through a local translator, who spoke English, French and Hassaniya, a dialect of Arabic. The translator, who did not want his name used for security reasons, also conducted followup interviews on CNN's behalf.

Design & development by Bryan Perry, Brian Duckett, Judith Siegel, Kyle Ellis, Nick Lusk, Thurston Allen & Ken Uzquiano