John Barrett watches over his young neighbors playing in the streets of their housing estate, The Oval, in Washington, England.

Washington, England — On a beautiful July day, everyone in Washington is basking in the sunshine. Tourists click on cameras as locals walk through leafy streets and by manicured lawns and gardens.

An American flag flies proudly from a mast at the Old Washington Hall, while stars and stripes adorn the sign of the Washington Arms pub.

But this is not Washington DC — this is Washington UK, or as the locals in this town call it, the “Original Washington.”

It was here, in northeastern England, that the ancestors of America’s first president, George Washington, inherited the family name before emigrating to Virginia in 1656.

It’s thousands of miles away from DC, but there is a great affection in England’s Washington for America. There is a July 4 ceremony every year, and there are tributes across the village, like a school and estate named after John F. Kennedy.

![]()

Ged Parker, a National Trust volunteer at Washington Old Hall, says, "The thing about Washington is that it has matured through the ages. From the Old Hall through Medieval England to the industrial revolution and the modern day. It is always evolving."

![]()

A welcome sign greets visitors as they arrive in Washington, a town near Sunderland, England.

US President Donald Trump arrives in the UK on Thursday and will be met by protests across the country. Despite Washington’s love for America, people here are not too excited by the President’s visit either. Even though the town shares a similar story to those in the US rust belt, where Trump finds his core support, people here have more to say about American presidents of the past.

People speak of Jimmy Carter, for example, with affection. Carter’s visit in 1977 to Newcastle and Washington remains one of the most fondly remembered visits by a politician to the area.

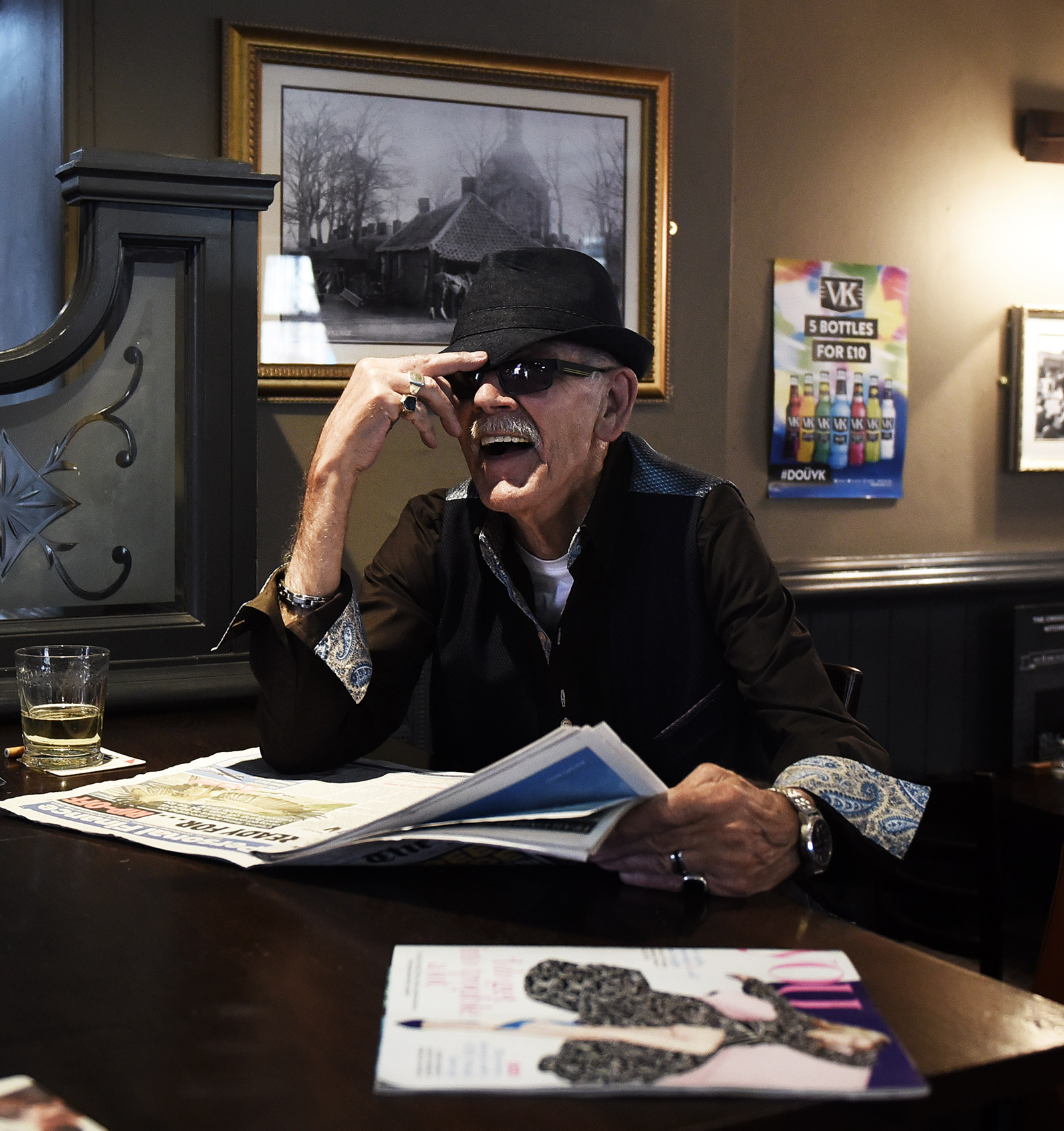

Sitting in the corner of the Cross Keys Pub, Hugh Alexander Barry recalls Carter’s visit, while shaking his head at the mention of Trump.

![]()

Hugh Alexander Barry, who has resided in Washington for most of his life, at the Cross Keys pub.

"I remember when Jimmy Carter came here and he was such a gentleman. It was a brilliant day. He was so approachable and he said how the welcome had made him feel at home,” says Barry, who’s in his 70s.

"But Trump? He's not for me. I don't personally like him and if he came into the pub I wouldn't have a drink with him. He's really a businessman who just wants his name everywhere. He's a bragger. Trump Tower, Trump this, Trump that. Trump off, mate."

Cigarettes and alcohol

Nestled in between Newcastle and Sunderland, Washington is the largest town in the country not to have its own train station. It is in decline — many of the families who live here remember their fathers and grandfathers working in the mines or in shipyards that no longer exist.

The old village may be the original Washington, but a five-minute drive from George Washington’s ancestral home is the neighborhood of Concord, an unremarkable place with a story of its own.

![]()

The wheel of the F Pit, where coal was mined for just under 200 years.

![]()

A monument to the coal miners in Washington.

The old miners’ houses are tightly packed together, and the gray hue of the pebbledash facades of homes has an eerie and depressing feel. Color is in short supply, save for the underwear hung on clothes lines across front yards.

The main street is a motley collection of pubs and betting shops punctuated with discount stores that stock everything from deodorant to dog food.

On the sidewalk, young mothers sit with babies in their strollers, sipping from energy drinks while puffing on cigarettes and scrolling through WhatsApp.

Nearby, a couple of men swig beer while putting the world to rights, as the English say.

![]()

Local people in front of shops selling low-cost goods on Washington’s main street.

‘When people have no hope’

The locals say Concord is a “rough part of town,” though the welcome could scarcely be warmer.

Inside the New Tavern pub, people down pints of beer and dance to the sounds of Third Beat Drop, a reggae band from down the road.

The pub is typical of the area, with England flags on every corner as World Cup fever grips the country. People here are generally far more interested in talking about football than politics.

But Paul White, the band's drummer, is keen to talk Trump, as well as Brexit, which has plunged British politics into crisis this week.

![]()

People listening to local reggae band Third Beat Drop in the New Tavern pub.

The northeast, and the broad Sunderland area, voted to leave the European Union with a majority of just over 61%.

Some people have tried to draw comparisons between Trump’s populism and Brexit. Trump at one point even called himself “Mr. Brexit.” But, as White says, a Brexit supporter is not necessarily a fan of Trump’s.

"There's no quality from the whole Trump camp," says White, who also works at a nearby furniture factory.

"I mean, when people have no hope, this is what happens. Walls in Mexico? Locking up kids? That's not the way to do it.”

![]()

Paul White, drummer from the reggae band Third Beat Drop.

![]()

A young boy cycles past the New Tavern.

He does see, however, how Washington UK is a bit like the American towns in decline, where Trump has legions of supporters.

"People are struggling. Wages are bad. Everybody's blaming foreigners. We need more hope."

‘Most generous people on the planet’

Hope is a word that so many in Washington utter, but they seem unsure where to find it.

A short walk down the road from Concord is Sulgrave, one of Washington's most deprived areas.

There is some irony in the “HopeSpring” sign outside a large ugly building that stands amid a concrete jungle and dilapidated shop fronts.

But take a step further around the corner and you begin to understand the strength of a community that feels it has long been forgotten by the rest of the country.

![]()

The Rev. Julie Wing at the St. Michael and All Angels church, which operates a food bank for local people in need, in Washington’s Sulgrave district.

Sitting inside St. Michael and All Angels Church, Rev. Julie Wing is meeting with volunteers of the local food bank.

In the past four years since she arrived at the church, demand for food has increased as local people struggle to make ends meet.

Many of those who live here work in local factories for car manufacturer Nissan, one of the area’s largest employers. A network of churches and businesses has come together with the local community to ensure that nobody goes hungry.

"I think that people who have nothing are the most generous people on the planet because they know how to pull together. They know what hard times are like. These pit villages still have a very strong sense of community,” Wing says, referring to the town’s mining past.

"It may not apply to some areas but certainly from what I've seen, when they have that sense of community they pull together. When times are bad, they give more. When times are good, they sell bread together."

![]()

The HopeSpring center is being converted into a place for community activities.

Wing is an effervescent character who radiates enthusiasm. But she does not hide from the reality of the situation.

She tells stories of Waterloo Walk, the estate opposite the church, where drugs are rife, loan sharks and private landlords target residents and grudges are sorted out by hitting people with large pieces of wood.

Many of the children in the local area are on free school meals because their parents cannot afford to feed them adequately.

Just a week earlier, a body was found inside an apartment nine months after the person died. Nobody had noticed the person was missing. Nobody had thought to check.

The situation troubles Wing, but she remains positive. Volunteers help where they can, local charities make sure residents get the right government benefits and Wing is on hand to help with pastoral care.

"This community punches above its weight. It's a great community, it's not miserable,” Wing says. “The community speaks to the church and the church speaks to the community."

![]()

Carl Sacco serves young customers Jensen and Millie in his sweet shop. The shop has been in his family since 1955.

Washington cherry balls

Back in Concord, the high street begins to get busy as local children make their way home from school.

Sacco's sweet shop is doing a roaring trade, with Aniseed Rock, blue raspberry snowies and Soor Plooms, the pick of the day.

Inside, Carl Sacco is weighing out more sweets for the latest group of kids hoping to spend their pocket money.

The place has the joyful feel of a traditional English sweet shop, the large plastic boxes full to the brim with treats of every color, including American-style candy.

Sacco was in Washington when President Carter came to visit, but he too is less sure about Trump.

![]()

American candy is sold in Sacco's Sweets shop.

"If Trump came in, would I sell him sweets? Well, I'd sell him some Washington cherry balls, but only if he paid for them.”

Further down the high street is Fatties Café, lovingly named after the owner's wife.

In the kitchen, Kelly Maughan is busy preparing a chicken dinner for an older couple who have come in to escape the rain.

"I'm not into politics," Maughan says, piling potatoes and broccoli on a plate.

"But Trump? He's a funny person, isn't he? If he came to Washington today, I think he'd need a hefty police presence. But then that's pretty standard round here on a Saturday night."

![]()

Matthew Allon and his dog, Spike, are pictured in Fatties Café, as Kelly Maughan works in the background.

Maughan's self-deprecation comes with a smile. She is Washington through and through, having spent her entire 35 years here.

"I grew up here. I understand that if you didn't grow up here and then came here then you might think, 'Oh God,'” she says.

"But this is our home. It's our community and everyone knows everyone. I wouldn't ever leave."