Inside the hospitals that concealed Russian casualties

Vilnius, Lithuania — As his daughters dozed off in the back seat, his wife filmed him driving, eyes narrowed, focused on the dark road ahead. Andrei, a doctor, had been plotting their escape from Belarus since 2020, when the Kremlin-backed regime cracked down on a popular uprising, sending the country spiraling deeper into authoritarian rule and engulfing it in a climate of fear.

When Russia launched its assault on Ukraine from Belarus’ southern doorstep, getting out suddenly felt more urgent. His family watched from the windows of their apartment block as helicopters and missiles thundered through the sky. Within days, Andrei — whose name has been changed for his safety — said he found himself being forced to treat Russian soldiers injured in Moscow’s botched assault on the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. Then, at the end of March, he was jailed on trumped-up corruption charges. After his release in May, and carefully weighing the risks, he decided it was time to leave.

So as not to spark any suspicion, Andrei asked one of their neighbors to sneak the family’s suitcases, filled with legal documents, a few clothes and a photo album, out of their building and stash them in a car. Late one Friday evening in August, after he had finished his shift at the hospital, they met in a parking lot without any security cameras to pick up their bags. Then the family set off.

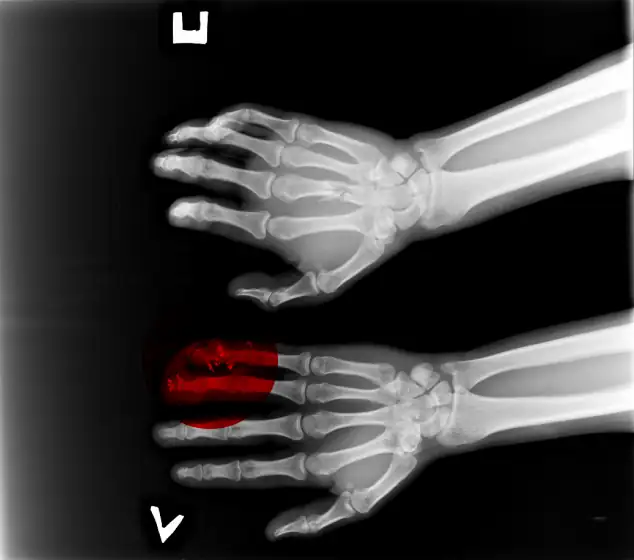

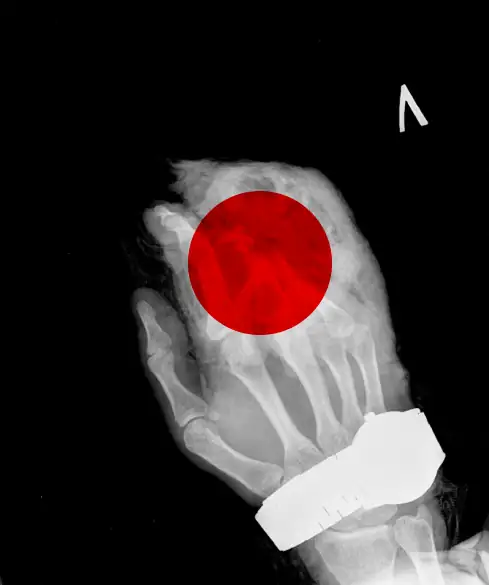

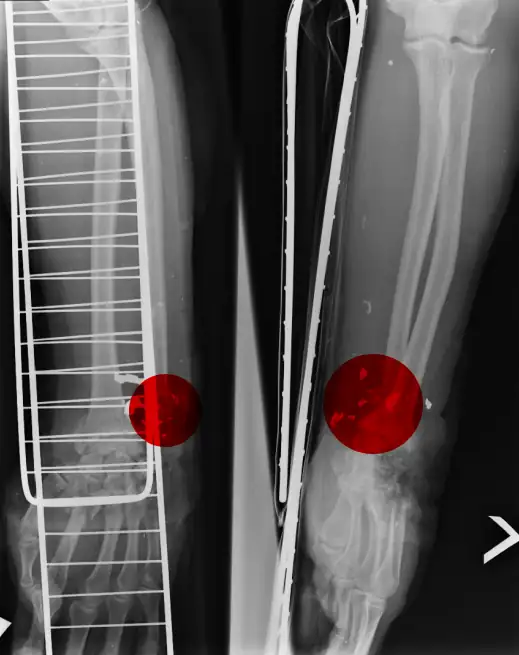

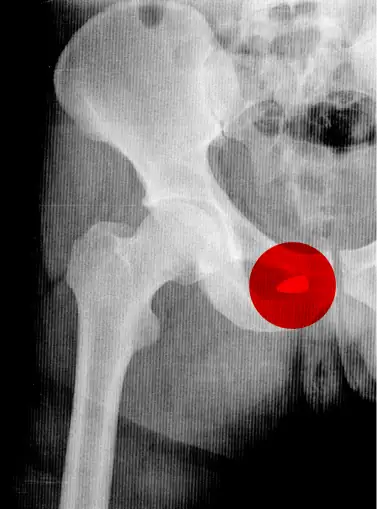

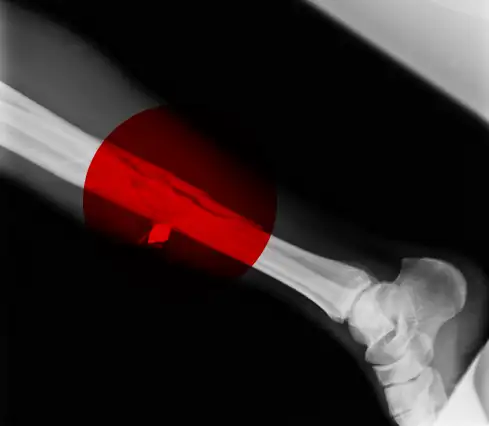

Videos obtained by CNN

It had taken Andrei months to chart out the best route — asking for advice over encrypted messaging apps from a Belarusian medical solidarity group, activist organizations and others living in exile.

Driving through the night, they traveled from their home in Mazyr, a city in Belarus’ southern Gomel region, more than 370 miles north to the country’s border with Lithuania …

… finally reaching the point where he had been told he could cross.

They stopped on a rural, dirt road and Andrei kissed his wife and girls goodbye. All being well, they would cross through the official border checkpoint and reunite with him in Lithuania, where he planned to claim asylum. Inside one of his daughter’s toys, Andrei had hidden a USB flash drive carrying evidence of what he had witnessed — dozens of X-rays of wounded Russian soldiers. He told them he loved them, turned and walked into the woods.

As Andrei made his way through tangled undergrowth, disoriented, he came across a Belarusian border police booth and felt a sense of terror — he knew his name was on a government list of people banned from leaving the country and, if his passport information was checked, he would be thrown back in prison.

Mercifully, the booth was empty. And when he reached the river bank, he swam as quickly as he could, his heart racing.

On the other side, Andrei recalled, a heavy-set Lithuanian man stood holding a fishing pole, his eyes wide. Speaking in Russian, he said it was the first time he’d seen someone fleeing. “Is it really so bad in Belarus?” the man asked.

“Yes,” Andrei answered, thinking back over all that Belarusians had endured at the hands of his country’s brutal regime, and now the bloody war they had been drawn into. “It is.”

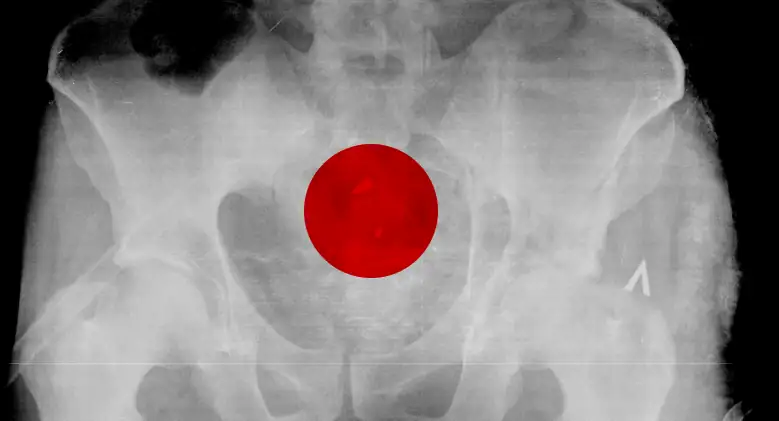

Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko allowed his close ally Russia in February to use the country, which shares a 674-mile border with Ukraine, as a staging ground for its invasion. With his permission, Russian President Vladimir Putin treated Belarus as an extension of Moscow’s territory, sending equipment and around 30,000 troops ostensibly for joint military exercises — the biggest deployment to the former Soviet state since the end of the Cold War. Russia erected temporary camps and hospitals in Belarus’ frozen fields, dispatching military hardware, artillery, helicopters and fighter jets near the border.

When Putin declared his “special military operation” in a pre-dawn televised address on February 24, he sent missiles, paratroopers and a huge armored column of soldiers rolling south from Belarusian soil, setting in motion what was intended to be a lightning strike to decapitate the government in Kyiv. But as Russia’s advance stalled and setbacks mounted, Moscow began to spirit wounded soldiers back across the border to Belarus for treatment in several civilian hospitals, a CNN investigation has revealed. The doctors working there were drafted into a war that they didn’t sign up for, unwittingly enlisted as quasi-combat medics and obliged by their hippocratic oath to provide life-saving care.

Many were forced to sign non-disclosure agreements, told not to speak about what they saw. Some, like Andrei, later fled. From their operating tables, Belarusian medical workers gained perhaps the clearest sense of the scale of casualties suffered by Russia in the early weeks of the war — describing young, shell-shocked soldiers who thought they were being sent for exercises only to find themselves losing a limb in a war they were ill-prepared to fight. While Lukashenko admitted that Belarus was providing medical aid to Russian military personnel, little is known about what happened in the hospitals where they were taken, which were kept under strict surveillance. In interviews with Belarusian doctors, members of the country’s medical diaspora, human rights activists, military analysts and security sources, CNN examined the role Belarus played in treating Russian casualties, while the Kremlin sought to conceal them. Their testimonies and documentation — including medical records — offer insights into the Belarusian government’s complicity in the Ukraine war, as fears mount that the country might be sucked further into the fight.

X-rays obtained by CNN

Exactly how many Russian soldiers have been killed or wounded in Ukraine remains a mystery to all but a few inside the Kremlin. The Russian defense ministry said on March 2 that early casualties amounted to 498 Russian soldiers killed and nearly 1,600 injured in action. But US and NATO estimates around the same time put the number of dead significantly higher: between 3,000 and 10,000. Seven months into the war, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu revised the official tally, saying nearly 6,000 Russian soldiers had died. The Pentagon said in August that it believed the true toll was much more: as many as 80,000 dead or wounded.

Belarus’ stranglehold on information — Lukashenko’s regime has put independent news media under severe pressure, restricted free speech and introduced new legislation extending the death penalty for “attempts to carry out acts of terrorism” — has provided useful cover for Russia in repressing details about its injured and dead. In recent months, a number of people have been arrested for filming Russian military vehicles, according to Viasna, a Belarusian human rights organization whose imprisoned founder was recently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

In spite of the repressive environment, hints of Moscow’s troop losses have emerged on social media and local reports. In late February, the Belarusian Hajun project, an activist monitoring group that tracks military activity in the country, started sharing images on Telegram of Russian medical vehicles ferrying fighters across the border from the frontline. Drawing on a network of trusted local sources, the group posted footage of green, Soviet-era “PAZ” buses marked with red crosses and a white letter “V” — a symbol believed to stand for "Vostok", or east — and armored ambulances in Gomel region.

Source: Mapcreator/Maxar Technologies

It appeared some were being taken to field hospitals, which had popped up near Belarus’ border with Ukraine.

February 22, at VD Bolshoy Bokov Airfield

Maxar Technologies identified a deployment of dozens of military vehicles, troop tents and a field hospital, set up at an old Belarusian aerodrome near Mazyr.

Source: Maxar Technologies

March 14, in Naroulia

Another field hospital — a larger grouping of beige tents — was detected in the town of Naroulia, closer to the Ukrainian border.

Source: Maxar Technologies

Other medical vehicles were spotted near hospitals in the cities of Gomel and Mazyr.

February 23, near Mazyr City Hospital

A photo shared on the eve of the invasion captured an armored ambulance outside Mazyr City Hospital.

Source: Belarusian Hajun project/Telegram

February 28, near Mazyr

Days later, a column of several medical “PAZ” buses were filmed driving on a local road.

Note: This video has been sped up. Source: Pravda Gerashchenko/Telegram.

February 28, at Mazyr Railway Station

One video showed men in fatigues outside Mazyr’s main railway station, appearing to carry wounded soldiers onto a train marked with the red RZD logo of the Russian state-owned operator Russian Railways.

Source: Mozyr For Life/Instagram

"We can confirm they (Russians) used Belarusian infrastructure, including medical buildings and field hospitals. They also used morgues ... and they used train stations or airbases to transport dead people or injured people, we have photos of that,” Anton Motolko, a Belarusian blogger who fled Minsk in 2020 and founded Belarusian Hajun project, told CNN. Motolko said his sources told him that morgues in the area were overflowing, and that a steady stream of wounded soldiers had arrived at Mazyr City Hospital, where Andrei worked.

In mid-February, Andrei watched in horror as his hometown of Mazyr seemingly turned into a sprawling military base — armored tanks rolled down the streets, Russian soldiers roamed local shops and got drunk at bars downtown. He and his family no longer felt safe, and avoided being outside after dark. Soon they began to suspect that Russia was preparing for war. As the military drills were due to wrap up on February 20, Andrei said his hospital administration extended a directive to treat Russian soldiers free of charge until March 10. "They must have thought the war would end by then,” Andrei said, adding that, two days later, Russian officers from the field hospital outside Mazyr cleaned out the city’s blood bank reserves.

On the morning of February 24, the first day of fighting, Andrei recalled a hospital official gathering all of the doctors into a meeting room, ordering them to keep 250 beds free for Russian casualties, stop all planned surgeries and send what Belarusian patients they could home. “Then they warned us that we were not allowed to share any information about Russian soldiers. We had to sign a non-disclosure form, forbidding us to share any photos, documents,” Andrei said. “They told us that we were being watched by the Russian Federal Security Services (FSB), that they had ways of monitoring our phones.” While he didn’t see any Russian FSB, Andrei said he did notice local Belarusian State Security Committee (KGB) agents stalking the halls of the hospital. Mazyr City Hospital did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.

“They warned us that we were not allowed to share any information about Russian soldiers. We had to sign a non-disclosure form, forbidding us to share any photos, documents.”

– Andrei, a doctor from Mazyr, Belarus

Aliaksandr Azarau, head of ByPol, an organization set up by ex-Belarusian police and security service members, told CNN that Mazyr authorities went to great lengths to keep information about the number of wounded Russian soldiers, and the types of injuries they sustained, under wraps. Azarau said that the KGB departments for Mazyr, along with the region’s department of internal affairs, put Mazyr City Hospital “under round-the-clock surveillance” while ”warning the staff of personal responsibility for disclosing information about military personnel undergoing treatment in the hospital.”

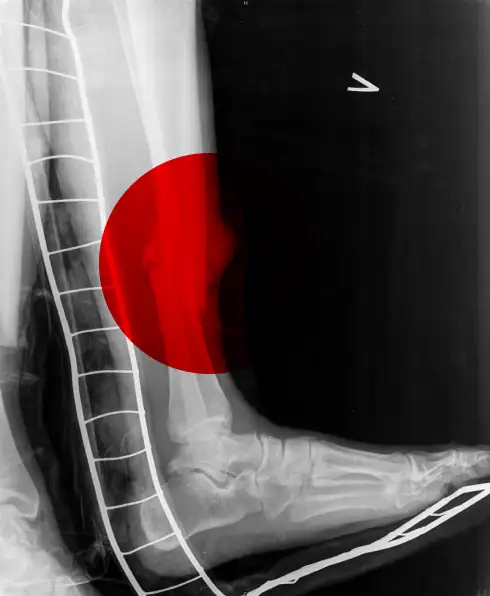

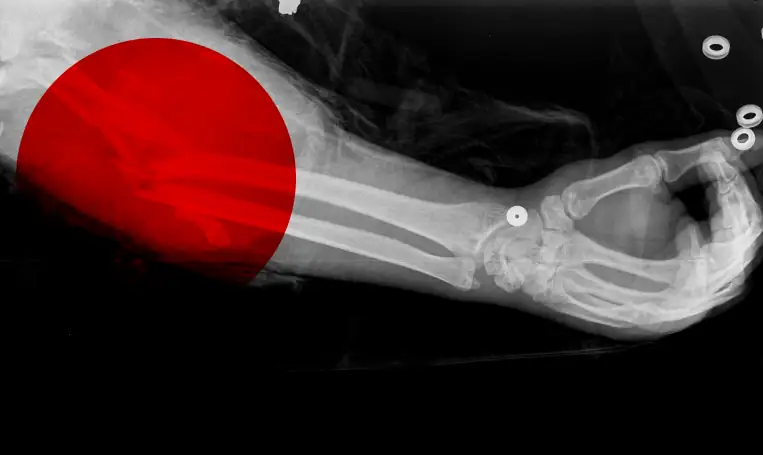

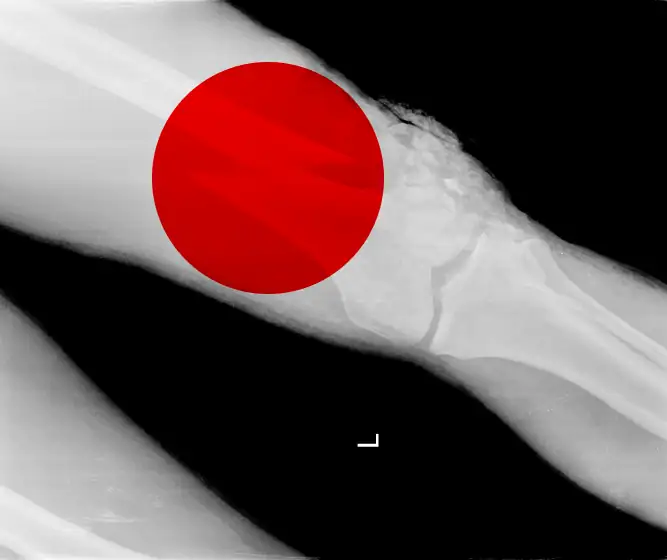

Still, Andrei managed to secretly photocopy the X-rays of dozens of troops treated at Mazyr City Hospital, which he shared with CNN. “What I took with me, that part of the archive, could have gotten me into legal trouble for espionage,” he said, adding that he had taken the risk to provide evidence of a side of the war that has so far gone unseen, smuggling them out of Belarus in his daughter’s toy cellphone. The scans included the names and ages of the soldiers, many of whom were between 19 and 21 years old, capturing their injuries in stark black and white.

X-rays obtained by CNN

Andrei said he saw the biggest wave of casualties arrive at Mazyr hospital en masse in the early hours of February 28. After receiving a call that the soldiers were incoming, the doctors assembled at the entrance to the emergency room around midnight, waiting. Soon, busloads of injured troops began to pour in. Russian soldiers carted them inside on stretchers, dumping them at the front doors, Andrei said.

The doctors quickly assessed the soldiers’ injuries, drawing numbers on their foreheads to mark them by priority, triaging their wounds and sending them off for scans or surgeries.

Altogether, more than 100 Russian troops arrived with injuries to the face, gaping wounds, compound fractures from explosions and coming under fire, Andrei said.

On the same day, a local state-run TV channel released a report claiming the hospital was running normally, which Andrei said he saw as an attempt to stymie rumors that it was treating Russian troops.

In reality, the hospital was full of soldiers, Andrei said. Some were missing eyes, others required amputations — having arrived with gangrenous, shattered limbs — a few were paralyzed, one had lost part of his brain, another his lower jaw. Several had been wearing tourniquets for days to staunch the blood, their bodies peppered with bullets and shrapnel, the X-rays showed. “There were more wounded, in need of an operation, than we had operating tables,” Andrei said. “The Russians just gave us their injured [soldiers], and didn’t give a damn about them.”

Many of the Russians had been fighting in areas outside of Kyiv — in Hostomel, where they suffered major losses at a key airfield, in Bucha and Borodianka, suburbs that they terrorized for weeks, and in Chernobyl, where their forces were exposed to radiation in the highly toxic zone known as the “Red Forest.” Andrei said he treated Russian paratroopers and special forces injured in the botched assault on Hostomel airfield, where they told him their helicopter came under attack. “They were professional killers. We had to treat them, that was our job. I felt disgusted by the whole thing. But, as a doctor, I am not really allowed to feel disgusted,” he said. Russian Major General Sergei Nyrkov, who suffered a severe abdominal injury in Chernobyl, was also treated at Mazyr hospital, according to his X-ray, which was among those Andrei smuggled out.

But the majority of the injured were young, inexperienced soldiers and conscripts from remote parts of Russia, Andrei said. Russia’s Ministry of Defense did not respond to CNN’s request for comment on these allegations or accusations it has co-opted Belarus to carry out an “act of aggression” against Ukraine, in violation of international law.

On March 1, at a meeting of Belarus’ Security Council, Lukashenko acknowledged that hospitals were providing Russian soldiers with life-saving treatment. “We treat them and will continue treating these guys – in Gomel, Mazyr, and I think in some other district capital when they are transported to us. What's wrong with that? Injured people have always received medical treatment during any war,” he said, before dismissing reports that Russia had suffered huge losses as fake news.

“Our self-exiled opposition and the rest shout about thousands of injured [Russian military personnel] delivered to Gomel. Nothing like that. We've treated about 160-170 injured in this entire period,” Lukashenko added.

But Andrei and other medical professionals in the region tell a different story. In early March, 40 to 50 Russian casualties were brought to Mazyr City Hospital every day, shuttled in and out again like a “conveyor belt,” Andrei said. Most arrived in the dark of night, or early in the morning, in green Russian military buses and ambulances. “We, the doctors at the hospital, thought that maybe they were worried about security, so they brought them under the cover of the night. They were afraid of road traffic to see the red cross on their vehicles. People would know,” Andrei said. The Russians also tried to bring the dead to the hospital, he said, adding: “They didn’t know what to do with them.”

Anna Krasulina, spokeswoman for exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, told Ukrainian parliamentary TV channel "Rada" in March that the morgues in Mazyr were flooded with the bodies of dead Russian soldiers. In April, Tsikhanouskaya met with members of the US State Department in Washington, DC, handing over evidence of Lukashenko’s involvement in the war in Ukraine. The documents, seen by CNN, detail how Belarus provided key infrastructure to Russia, including missile launch positions, railway lines, and medical assistance.

Citing open source information, Franak Via?orka, Tsikhanouskaya’s chief political adviser, told CNN that Russians were using hospitals in both the Gomel and Brest regions between the start of the war and April, but that there were also “many cases when doctors refused to take Russian soldiers,” describing this as grassroots resistance. He added that Russians have not been using infrastructure like hospitals in Belarus since April.

“There were more wounded, in need of an operation, than we had operating tables.”

– Andrei

Mazyr was one of at least three hospitals in Gomel region that treated Russian casualties, according to medical and security sources, who estimated that the facilities collectively cared for hundreds of soldiers. Mikalai, a doctor who left the region and whose name has also been changed for his safety, said that the Regional Clinical Hospital and the Republican Research Center for Radiation Medicine and Human Ecology were among those providing treatment, but that the latter was largely operating with Russian medical staff brought in for the war.

After receiving a patient transferred from the Republican Research Center for Radiation Medicine and Human Ecology, Mikalai said that he had been curious about how the hospital was operating. So, late one night, he drove slowly past the complex. “I saw when it started getting dark, military medical buses coming to the hospital … green-colored ‘PAZ’ vehicles, with their windows covered with white cloth,” he said.

Azarau, the head of ByPol, said that the Republican Research Center for Radiation Medicine and Human Ecology was used to treat Russian servicemen who took part in the assault on the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, some of whom showed signs of radiation poisoning. The hospital was originally built in the early 1990s to provide specialized medical care to the local population affected by the Chernobyl disaster.

Mikalai said it was no surprise that the Belarusian and Russian authorities went to great lengths to keep the reality of what was happening behind closed doors in these hospitals a secret. “A great number of wounded young soldiers is a dirty, dirty stain that does not correlate with the idea of this great Russian invasion,” he said, adding that the authorities wanted to give the impression that the situation was under control and reports of a huge number of casualties were fake. “But this is the bad truth … they tried to hide it.”

Reacting to CNN’s investigation, Tsikhanouskaya said that the testimonies from Belarusian doctors were “important evidence” of Lukashenko’s “crimes and complicity in the war,” and called on Russian troops to withdraw from Belarus.

“This is proof that the regime participated in and facilitated Russian aggression. But this is also a testament to the courage of those Belarusian doctors. They, despite threats and terror, recorded the truth so that Belarusians and the world would learn what Putin and Lukashenko are actually doing in Ukraine,” she said in a statement, adding that the Lukashenko regime’s participation in Putin’s war “must not doom the Belarusian people to the role of pariah.”

Unpicking the role that Belarus has played in the Ukraine war has taken on new urgency since Lukashenko announced in October that Russian soldiers would deploy to the country to form a new, “regional grouping” and carry out joint exercises with Belarusian troops, raising fears that he might draw the country more directly into the conflict.

“The fact is that Belarus long ago ceded its sovereignty in significant ways to Russia,” State Department spokesperson Ned Price said in a briefing on October 12, responding to a question about Belarus’ posturing, which the United States is monitoring closely. “The fact that President Putin has been able to use what should be sovereign Belarusian territory as a staging ground, the fact that brutal attacks against the people of Ukraine have emanated from a sovereign third country, Belarus in this case, it is another testament to the fact that the Lukashenko regime does not have the best interests of its people at heart.”

Not only has Russia infringed on Belarus’ sovereignty, it has also posed a serious challenge to NATO — three members of the alliance share a border with Belarus. Putin has been laying the groundwork to transform Belarus into a vassal state for some time. After a rigged presidential election in 2020 cemented Lukashenko’s long reign, triggering widespread pro-democracy protests, he clung to power with the help of Putin. Russia backed the ruthless crackdown on demonstrations, and gave Belarus a $1.5 billion lifeline to evade the brunt of sanctions, but it came with strings attached. Beholden to the Kremlin, Lukashenko has supported Russia’s military actions from the sidelines, so far avoiding sending his own troops into the fray. But he may be forced to shift his position, as Putin racks up losses.

“As far as our participation in the special military operation in Ukraine is concerned, we are participating in it. We do not hide it. But we are not killing anyone,” Lukashenko said in early October. “We offer medical aid to people. We've treated people if necessary,” he added.

Still, many in Belarus are terrified that might change. A majority of Belarusians do not want their country to take part in the war, according to a recent Chatham House poll conducted online, which found that only 5% favored sending troops to support Russia. Andrej Stryzhak, a Belarusian human rights activist and founder of BySol, an initiative that supports victims of political persecution in Belarus, who himself faces politically motivated charges for “funding extremist formations,” said that the organization saw a surge in requests for help when the invasion started. The group set up a Telegram channel with advice on how to flee abroad, for people who don’t support the war or were afraid of being mobilized themselves. “We took more than 10,000 consultations … and now we have a Telegram channel with 30,000 subscribers,” Stryzhak said, adding: “It’s very intensive work for us.”

Andrei reached out to BySol for help getting out of the country, but in late August, with the borders to Ukraine and Russia largely impassible, they were unable to assist him. In the end, he was aided by an informal network of Belarusian dissidents living in exile in Lithuania, who identify potential crossing points. They said they too have seen a surge in the number of Belarusian men fleeing for fear they will be forced to fight in Ukraine.

Having seen the havoc that the war has wrought first hand, Andrei said he was concerned that he might be sent into Ukraine as a combat medic. In Russia, doctors are increasingly coming under pressure. Earlier this month, Russian state-run news agency Tass reported that physicians in St. Petersburg received letters from authorities telling them not to leave the country for “security reasons,” and Russia’s parliament said around 3,000 doctors could be called up as part of Putin’s “partial mobilization” of troops.

In late March, Andrei was arrested alongside dozens of other Belarusian doctors, many of whom specialized in surgery, on charges of corruption and receiving bribes, which he denies. After being jailed in the Belarusian capital Minsk for a month and a half, Andrei said he got the sense that their detention may have been an intimidation tactic — to make them think twice before leaving the country. When he was released, he said he was contacted by his local military branch and told to enlist in the army. “I was asked to come to the military enlistment office with my documents … Of course, I didn’t go there,” Andrei said. He fled the country shortly after.

Now settled in another European country with his family, Andrei is relieved to no longer be wondering when or if he might be sent to war. Instead, he’s focused on sitting national medical exams so he can start to practice again in his new home.

“Ukraine is very dear to me. I was worried about my close friends and family living there,” he said, adding that Belarus’ complicity in the war was unbearable. “We wrote to each other ‘Slava Ukraini,’ saying that Ukraine was going to win. My relatives said that we would all outlive all of this. And yet the bombs were being launched at them from the territory where I lived.”