Story highlights

Alexander Calder was one of the most innovative sculptors of the 20th century

Artist is now the subject of two major exhibitions in London

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture at the Tate Modern looks at his life's work

The Calder Prize: 2005-2015 at Pace London brings together young artists who channel the artist's spirit in some way

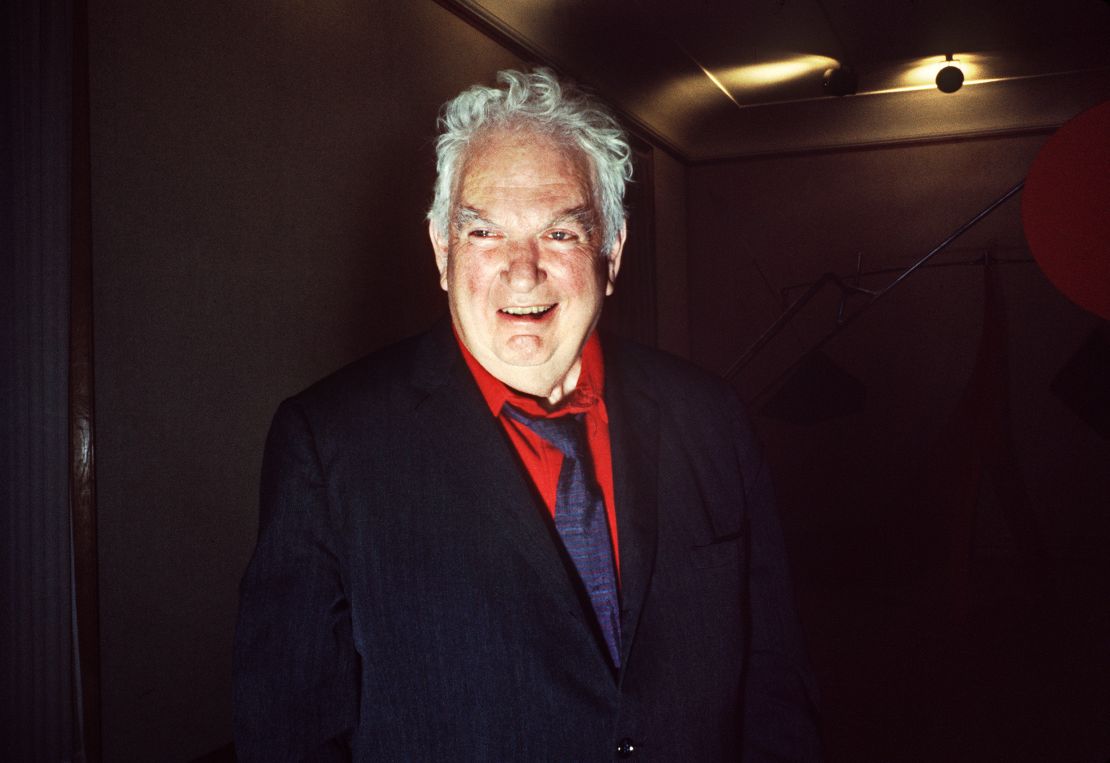

Alexander S.C. Rower talks about his grandfather with the authority of a historian, the enthusiasm of a fan, and the charm of a silver-tongued dealer. “Literal fist fights,” is how he describes the art world’s response to his famous relative Alexander Calder’s radical wire sculptures of the 1920s.

Calder, who died in 1976 when Rower was 13, was one of the most prolific sculptors of the 20th century. A true multi-disciplinarian, he first made his name with revolutionary wire molds – much to the outrage of the traditional art establishment.

The renowned American artist also branched into large-scale abstract sculpture, jewelery design, toy-making and the performance of an extremely detailed miniature circus, among many other things.

Then there are the mobiles – hanging kinetic sculptures that appear and disappear depending on where you’re standing, the wind, and the movement in the room. His were not intended to hang in a nursery, but the idea is much the same.

In London, Calder is now the subject of two major exhibitions: Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture at the Tate Modern, which opened last November, and the newly opened The Calder Prize: 2005-2015 at Pace London, which brings together the winners of the biannual award with works by Calder himself.

Family business

The way Rower tells it, Calder’s forgoing bronze and clay for common industrial wire in sculpture “really pissed people off.” While his moving to abstract sculpture after building a reputation with wire is described as: “like Prince changing his name.”

Since 1987, Rower has been the go-to for any exhibition, book, or tribute to Calder, after he founded the Calder Foundation at 24.

“It began with a desire that people should understand what it was he made, and the context. These wire sculptures weren’t just these cute things… I was frustrated because his intellectual life had been shoved aside,” he says.

It’s something Rower was acutely aware of even before he started cataloging and archiving Calder’s life’s work – everything from major sculptures to throwaway sketches. Rower remembers being struck by the thoughtfulness of Calder’s process when he was a kid making toy swords in his studio.

“My family is really small, we’re really close, so I was around him a lot. And he was a very serious guy,” he recalls.

“He was very rigorous in his work, and his process was intuitive. He made things in an intuitive process, so if he stopped in the middle, he’d choose something and come back and it would change and become something else. The energy would change.”

While most of the the Foundation’s work is dedicated to preservation and education, outreach has long been a part of their mandate.

In 1989, they started Atelier Calder, an artist residency at Calder’s studio in Saché, France, and in 2005 the biennial Calder Prize was born. Every two years, an artist is chosen based on anonymous nominations from art world insiders, and awarded a three-month residency in Saché and $50,000.

“It’s $50,000 for doing nothing, only what you’ve already done. It’s an acknowledgment of an artist’s hard work,” explains Rower.

“You can pay for your kid’s education, or you can make art with it, or you can go on a vacation no strings attached. It’s just about supporting an artist.”

Bringing Calder into the 21st century

The Pace group show is the first time the winners – Tara Donovan (2005), ?ilvinas Kempinas (2007), Tomás Saraceno (2009), Rachel Harrison (2011), Darren Bader (2013), and Haroon Mirza (2015) – have been exhibited together in this context. Each artist contributed works of their choosing, knowing they’d be displayed not just among the work of their peers, but also of Calder himself.

The overall effect is captivating. Loops of magnetic ribbon floating hypnotically under an oscillating fan; there’s a shapeless mass of misshapen steel Slinkys; a lone speaker fills the room with pulsing bass; a multicolored square of light is affixed to a wall.

Upstairs, a room is filled with TV screens, speakers, and discordant sounds timed perfectly to create the illusion of music – courtesy of 2015 winner Mirza. Interspersed throughout are Calder’s sheet metal sculptures, wire figures, and hanging mobiles.

“I was very excited when they proposed this show to me,” Rower says. “It shows Calder in the 21st century. What is the Calderian effect that is going on?”

Somewhat surprisingly, the exhibition features few mobiles.

“His legacy lives on not only in the works he left behind, but also in the ideas and motivations he continues to inspire,” inaugural prize winner Tara Donovan said in the lead-up to the exhibition.

Similarly, 2013 winner Darren Bader said of Calder’s influence: “Being an integral part of so-called Modern art, he’s had incalculable influence on how I think. Like so many of the Modernists we continue to revere, he asked good questions.”

Ultimately, this is what Rower believes Calder’s lasting impact will be: challenging artists and spectators alike to think differently about what art can be, and how it can be experienced.

“It’s not like Calder made this and it physically inspired the artist to make this,” Rower says. “The line between Calder and each one of these artists is really about ideas.”

The Calder Prize 2005-2015 is on at Pace London, Burlington Gardens until March 5, 2016

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture is on at the Tate Modern until April 3, 2016