Editor’s Note: Artist Takashi Murakami is CNN Style’s latest guest editor. He has commissioned a series of features on identity. JJ Charlesworth is an art critic and senior editor for ArtReview. All opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.

When faced with catastrophe – war, famine or natural disaster – most peoples’ first priority is simply to survive. Art is often not made until the aftermath, by those who survived or were far away.

It’s this distance – of both time and place – that produces the tensions at the heart of art’s response to human catastrophes, since, in the end, the question asked of such an artwork is always: What good can this do?

In recent years, however, a sense of impending disaster has become an everyday aspect of cultural and political life – the threat of terrorism, the tragedy of the migrant crisis and, hanging over it all, the specter of the climate crisis. In such a zeitgeist, artists are making works that respond to current issues and anxieties in increasingly direct ways.

Take, for example, Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, who last December transported 30 icebergs from a Greenland fjord to the doors of London’s Tate Modern to highlight (if it needed emphasizing further) the urgent threat of climate change. And, perhaps more controversially, one of the most hotly debated artworks at this year’s Venice Biennale was Christoph Büchel’s “Barca Nostra (Our Boat),” the wreck of a ship that sank in the Mediterranean in 2015, killing an estimated 800 migrants as they attempted to make their way to Europe.

Situated on a Venice quayside, with little comment or explanation, the work sparked intense debate over whether it was a justified moral protest against humanitarian disaster and a memorial to its victims, or whether, by contrast, it disrespected those who died inside its hull, turning their deaths into an exploitative spectacle of human suffering. Among the most persistent criticisms of Büchel’s work was that, in the context of the Biennale, it turned the death of migrants into entertainment for well-heeled, Prosecco-sipping cultural tourists.

How, then, might we make sense of an artwork’s contemporary engagement with suffering and disaster?

In her 2003 essay on photography, “Regarding the Pain of Others,” Susan Sontag recognized that art′s claim to moral purpose relates to our proximity to the event, but also our own capacity for action or inaction – whether seeing others’ suffering will rouse us to the indignation and action, or instead desensitize us, reinforcing our indifference. Compassion, she wrote, “is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers … If one feels that there is nothing ?we? can do – but who is that ?we?? – and nothing ?they? can do either – and who are ?they?? – then one starts to get bored, cynical, apathetic.”

Sontag was writing in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, an event that turned disaster into a grotesque global TV spectacle, amplified by the new era of 24-hour rolling news. Almost two decades later, with images of tragedy now delivered instantly to our phones, things have only become worse. And one could argue that 9/11 inaugurated a paralyzing sense of awed fascination when faced with images of disaster from which we have yet to recover.

Sontag was writing in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, an event in which disaster had turned into a grotesque global TV spectacle, amplified by the new era of 24-hour rolling news. Almost two decades later, with images of disaster now appearing instantly on our smartphones, things have only got worse, and one could argue that 9/11 inaugurated a paralyzing sense of awed fascination faced with the image of disaster from which we have yet to recover.

Artists themselves are not immune to this fascination. After the attacks, music composer Karlheinz Stockhausen foolishly declared 9/11 “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos,” while artist Damien Hirst called it “visually stunning.” Compared to this, what good can art do?

Making sense of the horror

The question, perhaps, has something to do with how artworks can allow catastrophic experiences to be worked over and made sense of, both by those who suffer them and those who come after.

The processing of human catastrophe underpins a number of key works from Western art history. Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937), for instance, memorializes the victims of the aerial bombardment of the titular Basque town during the Spanish civil war, becoming both a modernist masterpiece and an emblem for the fight against fascism across the world.

Produced a century earlier, in the wake of Napoleon’s bloody conflict with Spain in the Peninsular War (1807-1814), Francisco Goya’s legendary lithographic series “The Disasters of War” remains a horrific, desolate and lasting example of art’s power to confront man-made horror. Even now, its unrelenting depiction of executions, rape, torture and corpses dumped in mass graves is profoundly shocking.

Goya’s captions to the “Disasters” frequently insist that we look at, and accept the truth of his own witness – “I saw this,” one reads, “this is how it happened” reads another – while simultaneously admitting that looking can be unbearable. “One cannot look at this,” reads the caption to an image in which a group of men and women huddle in terror before a firing squad that stands unseen, save for the muzzles of their rifles poking into the frame.

And yet, we keep looking at the horrors that unfold through the “Disasters.” Are we deriving a twisted, gratuitous pleasure from these images?

Facing horror and disaster through art is fraught with ambiguity about our own place of witness. How, after all, do these 200-year-old images differ from the videotaped atrocities circulated by today’s terrorists to further frighten and demoralize us, to desensitize us and drive us to apathy, as Sontag feared?

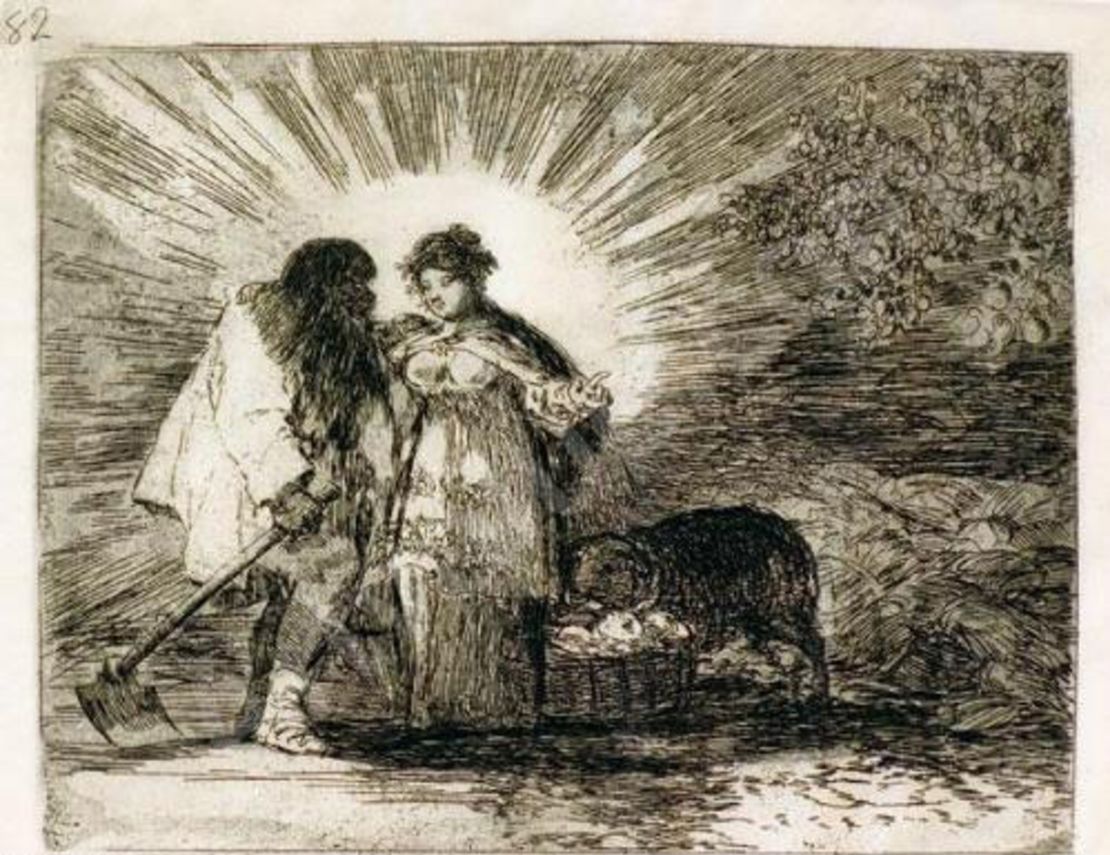

The last image of the “Disasters” series offers an answer of sorts. Unlike the others, it depicts a realistic scene, yet it is freighted with symbolism. It shows a couple – a woman, brightly illuminated and radiant, almost supernaturally so, with her arm around a stooped and careworn laborer. She points him – and us – to the scene of pastoral abundance around them: wheat sheaves, fruit trees, a lamb by her feet. “This is the truth!” Goya’s caption exclaims, paradoxically. The truth of what, though? Not of how things were, but of how things should be: happy, prosperous and peaceful.

What is at stake in Goya’s fantastical last image is the triumph of life over death. It is an imaginary resolution, a catharsis or, in the religious terms Goya would have been familiar with, a form of redemption. Similarly, while the bombing of Guernica was horrific, the painting of “Guernica” offered an experience that mediated that horror, taking death and turning it into an artwork that itself absorbs death. Art like this is challenging because it offers us a place in which we can work through, for ourselves, the experience of catastrophe – to decide whether we can find our own way to overcome it.

These historic artworks consider the disasters of the past from the vantage point of those who overcame them in the present. But today, the present itself appears to have become “disastrous” – a state of imminent catastrophe.

Works such as Eliasson’s and Büchel’s might be seen as calls to action, or as activism. The question for them, and other artworks today, is whether they inspire a sense of how catastrophe might be overcome, or whether they ultimately reinforce our sense paralyzed passivity when faced with images of human tragedy.