In January I sat next to a masked man on a J train from Brooklyn into downtown Manhattan, where a political protest was taking place. When the train stopped at Fulton Street, the man turned and wrote a message in black pen on the window of the subway car: “Every Act is an Act of Protest.” He disappeared into the crowd on the platform and his proposition stood there, suddenly authorless. I wondered what it meant.

Contemporary artworks are often presented as if they are acts of political protest. This often feels suspect in a world where artworks are luxury commodities. The anonymity of graffiti allows it to be a subjective expression of social truths, without being undermined by the commodification of identity. Anonymity, however, can also be a perceived as a weakness: a refusal to stand by what you believe and or inability to develop ideas throughout a lifetime.

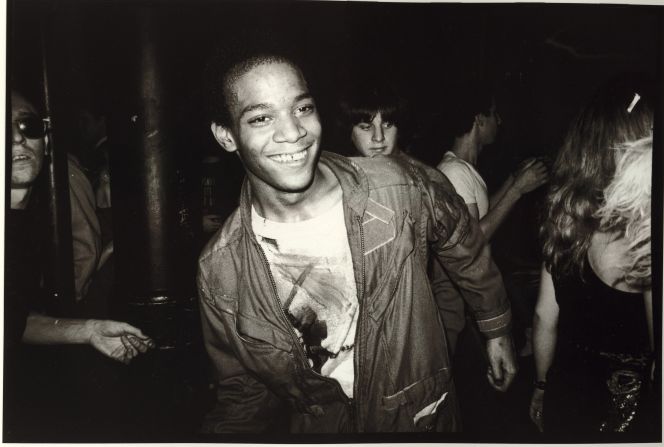

“Basquiat: Boom for Real,” an exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery in London, includes Jean-Michel Basquiat’s early work as a street artist alongside the paintings that made him the most famous American painter of his generation. Curated by Dieter Buchhart and Eleanor Nairne, it is the first large-scale exhibition of Basquiat’s work in the United Kingdom, and shows how his paintings move between street art and fine art, anonymity and identity, act and protest.

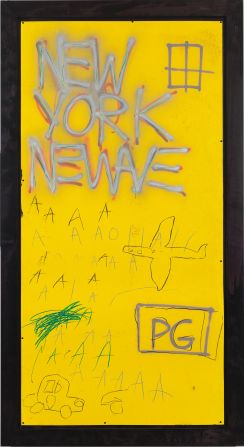

In 1978, Jean-Michel Basquiat began to tag Lower Manhattan with Al Diaz, his friend and classmate at the alternative City-As-School High School. Born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent, Basquiat had been interested in art from a young age: he visited art museums in the city and fantasized about becoming a cartoonist. As a teenager, he became involved with a theater troupe, and developed the character of SAMO, a salesman of fake religion, which developed into a tag that became notorious among the creative community of Lower Manhattan. Their artworks included political and theological statements (“SAMO… AS AN END TO THE POLICE…”) and claims that seemed to mock the extravagant claims of modern art (“SAMO? FOR THE SO-CALLED AVANT-GARDE”).

I emailed Diaz to ask why they chose to start in Lower Manhattan. He responded: “We first began to post our SAMO graffiti in TriBeCa, Because I had a girlfriend who lived in the area and we were beginning to spend a lot of time there. It would soon spread into the surrounding areas of The West Village, SoHo, Chinatown/Bowery and into the Lower East Side. These were all the areas we frequented and naturally we wrote wherever we went. These neighborhoods pretty much constitute what is generally referred to as Lower Manhattan. Undoubtedly the epicenter of all creative activity in NYC during the 1970-80s.”

Towards the end of 1979, Basquiat started making works on canvas, first under the name of SAMO and then, after declaring SAMO to be dead, using his own name. Given that they had been mocking modern art, this seems like a surprising turn.

“Both JMB and myself had art backgrounds even as teenagers and were very aware of art & art history, surrealism, minimalism, art performance, etc. A large amount of the art we saw was what we thought of as ‘Elitist and inaccessible. Intended for Educated White folks.’ Our SAMO Graffiti would often mock, criticize or simply make observations on this subject and its bourgeois (Boosh-Wah) participants. We never asserted that Our Graffiti was art. Our writings were, at their most ambitious, ‘poetic.’ We worked at sounding clever but were not under the impression that we were creating art. Perhaps ANTI-ART if anything,” Diaz wrote me.

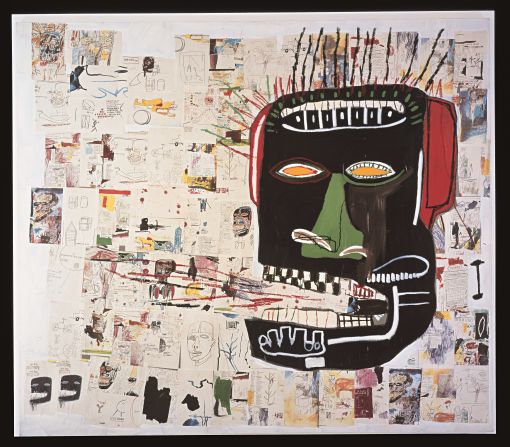

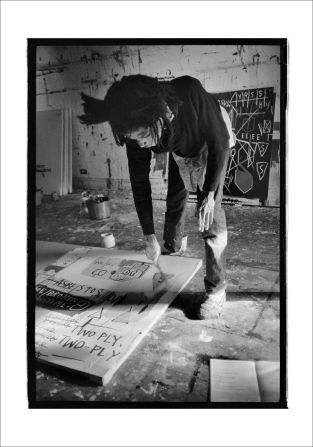

Between 1979 and his death from a drug overdose in 1988, Basquiat produced a large and distinctive body of work that combined a deep engagement with the masterpieces of Western painting with references from graffiti, cinema and jazz. The curator Eleanor Nairne tells me that the paintings are “rich compositions, dense with references,” which the Barbican exhibition tries to honor.

“The whole exhibition is underwritten by a huge research project, which is being condensed down into his work. We try to equip visitors with as much of that as possible,” she said.

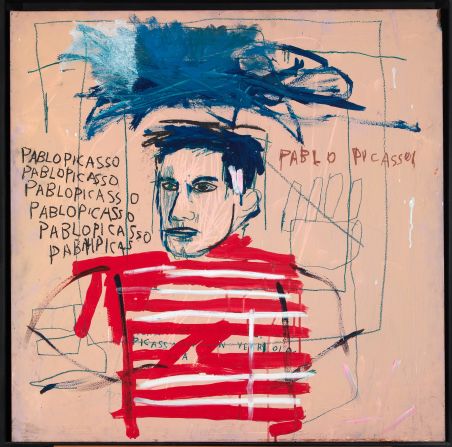

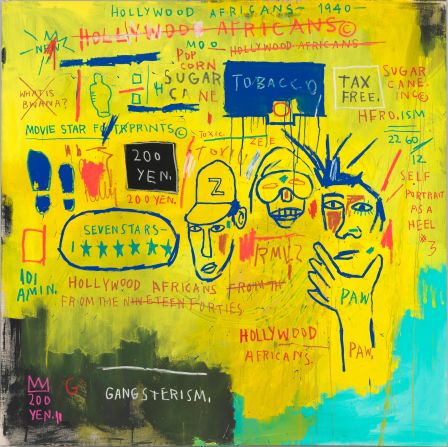

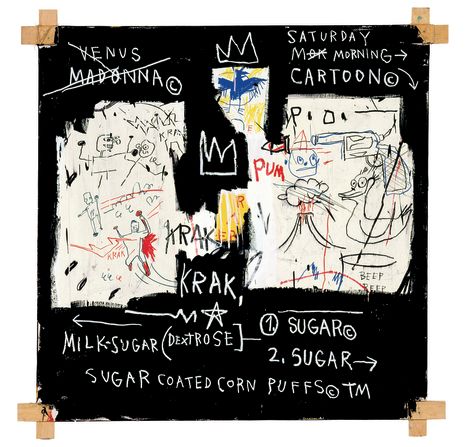

Basquiat was inspired by the artist Cy Twombly, who scrawled the names of classical figures on his paintings. Basquiat’s words are drawn from historical research and witnessing of the present. In “Untitled” (1984), a painting made for an exhibition in London, the word “Sugar,” invoking the use of slaves on British sugar plantations, appears alongside the struck-through word “NSIBIDI,” a West African ideographic script. Basquiat’s work protested the exclusion of black culture from Western art, and helped ensure painting could no longer be seen as a white institution.

He also witnessed the social antagonisms of the present. In 1983, he painted “Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart)” onto the wall of his friend Keith Haring’s studio, in memory of a young graffiti artist who died at the hands of the New York police officers. In “Widow Basquiat,” a memoir of Basquiat’s girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk, she is quoted as saying “Everything he did was an attack on racism.”

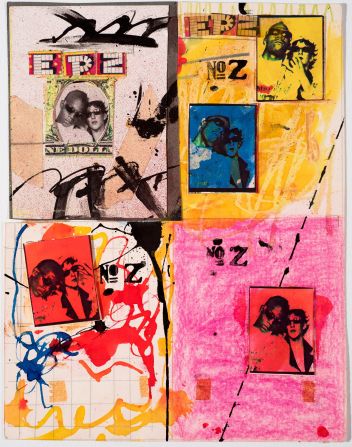

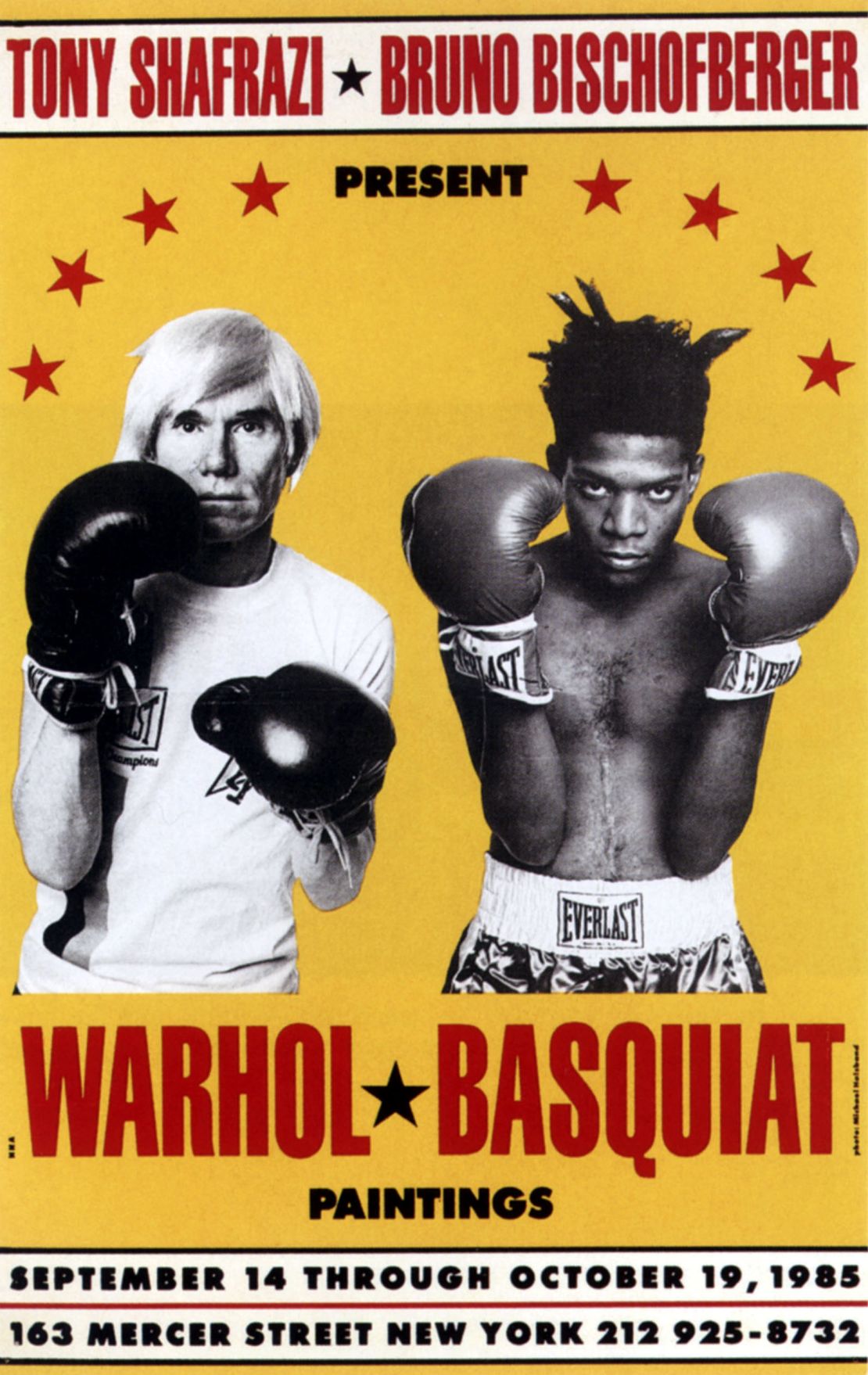

In 1983 Basquiat became friends with Andy Warhol, and in the following two years they collaborated on over 100 paintings. One of those works, “Arm and Hammer II” (1985), takes its background from a baking soda brand logo: a red circle in which a white arm wields a white hammer. Writing in the Barbican catalog, assistant curator Lotte Johnson suggests this symbol could be read as “the epitome of valorised white labour.”

In the painting, the logo is duplicated. In one, the white arm is replaced with the head of Charlie Parker, the jazz musician who Basquiat listened to obsessively. Parker is pictured with a saxophone in his mouth, blowing blue bubbles from it. Above his head is the word “LIBERTY” and, underneath, “1955,” the year of his death. It seems to be a design for a commemorative coin, but the words “COMMEMORATIVE” and “ONE CENT” are struck through, as if to ironize the idea that this would be a fitting tribute to the liberty that jazz made audible. Basquiat’s belief in that liberty was sincere: in a 1985 interview for the “State of the Arts” TV series, he said musicians could be heroes, and he felt that artists could be heroes too.

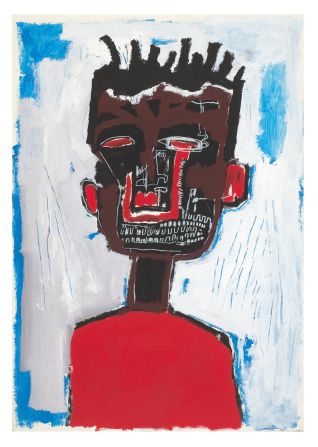

The heroism represented in his paintings is complex. Basquiat is often associated with neo-expressionism, a movement in painting that insists on the expression of the artist’s true self or real feelings through gestural brushstrokes, but this isn’t entirely fair. In the “State of the Art,” interview Basquiat said he thought he was making historical documents, and his work doesn’t represent a single, identifiable self.

“Untitled” (1981), like a number of other paintings, includes variations of the name “Aaron.” While Basquiat’s father understood it to be a reference to baseball player Hank Aaron, Nairne posits other allusions: a character in Shakespeare’s play “Titus Andronicus,” and the brother of Moses in the Old Testament. The name is also related to two letters which also feature individually in the painting, “A” and “O,” which relate to a passage from scripture that fascinated Basquiat: “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.” (Revelation 22:13)

This expressive grandiosity is counter-balanced by the graffiti aesthetics of Basquiat’s writing and drawing: his work promotes a heroic self at the same time as admitting it is artificial, provisional and improvised. Perhaps it was this that inspired the late art critic John Berger to remark on “Basquiat’s immense solitude.”

I asked Diaz how the Lower East Side has changed since SAMO began, and he wrote: “Like every and any area that becomes ‘COOL,’ developers and big money follows closely behind. By the mid-90s it was clear that it would become the next DESIRABLE AREA. By the mid-2000s it was completely gentrified. Now in 2017 some blocks that perhaps were once well known HEROIN MARKETS resemble streets in busy Mid-Town shopping districts. Gentrification can only be controlled if an affordable housing law is put in place covering large areas. Probably Utopian and unrealistic economically.”

But this mixture of political frustration and probably utopian ideas motivates his street art. In late 2016, Diaz began to use the SAMO tag again, bringing back to life the ironic, anonymous hero invented by two teenagers almost 30 years ago.

Earlier this year one of Basquiat’s paintings sold for $110.5 million, surpassing Warhol’s record for the most expensive American artwork in history. Basquiat’s popularity among dealers and collectors inspired derision from the art critic Robert Hughes, who in 1988 claimed he was “a small, untrained talent caught in the buzz saw of artworld promotion.” And that perception of his work as naive and wild persists today.

If the thoughtfulness of Basquiat’s work has been obscured, the Barbican exhibition helps to restore the significance of his paintings as historical documents. Nairne said: “There is a seismic emotional impact of this work which you can only get if you are physically in front of his paintings.”

Lamentably few of Basquiat’s paintings are in public collections, making an exhibition like this all the more important. It could inspire someone to discover a power to act that had been hidden from them.

“Basquiat: Boom for Real” is on at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from Sept. 21, 2017 to Jan. 28, 2018.