From an ancient Roman anti-wrinkle cream recipe to the 12th-century “Trotula,” a set of medieval manuscripts with formulas for skin care, hair dye and perfume, the desire to make ourselves more presentable – and even attractive – stretches back through history. And rather than embracing the subjectivity of beauty, societies have instead categorized and quantified these elusive qualities into prescriptive beauty “standards.”

These standards respond to the shifting political and social landscapes – and they continue to change with the times, according to beauty and wellness writer Kari Molvar.

“So much about how beauty is being defined right now has a political undertone to it,” she said in a phone interview, noting how both the Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movements have inspired responses from the beauty industry.

In her forthcoming book, “The New Beauty,” Molvar charts the evolution of beauty standards – and the forces that influenced them – from antiquity to present day. It is a timely reminder that the eye of the beholder has been shaped by everything from industrialization to gender politics.

From farm to face

In the 17th century, Europe was a growing center of global commerce. A network of trade routes, reaching far-flung places, brought new and exciting foodstuffs to the continent. Pepper and sugar, as well as new meats, cereals and grains, were now on offer – and they were not only available to the old upper class but also to the gentry, a new breed of wealthy landowner.

“All of this naturally led to plumper bodies,” Molvar writes in her book, “which forged a new beauty aesthetic.”

Renaissance artists, like Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens, helped establish the fuller figure as a new body ideal. Buxom women with soft physiques were idolized on the easel – dimples, ripples and all. But it wasn’t entirely progressive, Molvar noted. “It’s a shape that is largely celebrated for its biological function, fertility,” she wrote. “And ability to fulfill the desires of men.”

Around 300 years later, another shift in agricultural rhythms saw a new aesthetic emerge in the US. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the arrival of the “Gibson Girl,” a character devised by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, with long legs and a cool, detached air. The Gibson Girl represented a new kind of wealthy, educated American woman – emblematic of the new freedoms of the industrial age, despite hailing from a class that was likely never encumbered by farmwork.

Gibson’s creations could be found in the pages of Life magazine, frolicking outdoors or engaging in high-energy pursuits like horse riding or swimming. These hobbies trickled down through society to shape a new beauty standard, Molvar wrote. Defining features were a slim, athletic build and windswept hair piled high and loosely fastened.

Beauty as liberation

Beauty standards may be oppressive by their very nature, but sometimes they’re shaped by the empowering act of shirking societal norms. In her book, Molvar details the “certain amount of liberation” afforded to some White Western women during the 1920s, and the impact this had on style.

Attitudes toward domestic life and motherhood changed: “Depending on her means, a woman could work, stay out late, travel, drive a car, smoke, drink, marry or not.”

The desired silhouette moved from corseted curves, cinched in at the waist, to a straighter, more androgynous shape that “freed women’s bodies.” The purpose of makeup evolved from simply smoothing one’s complexion to being something “intended to shock, and stand out,” Molvar wrote.

Molvar also noted the emergence of the “Black is Beautiful” movement from the 1950s to 1970s. The phrase was, in part, popularized by the work of photographer Kwame Brathwaite, who shot portraits of dark-skinned models wearing Afrocentric fashions with their hair in afros or protective styles.

“It was a way to come up in a beauty system that privileged European notions of beauty,” Tanisha C. Ford, co-author of the book “Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful,” told CNN last year.

Brathwaite’s art encouraged Black communities to embrace their natural features, despite prevailing beauty standards being overwhelmingly White. “African American women and men expressed their political support for the cause through their physical appearance,” Molvar wrote, “choosing to leave their hair free … in lieu of straightening or styles that conformed to the standards of white society.”

The initiative aligned with the civil rights movement of the 1960s and illustrated how powerful – and political – cosmetic rituals could be.

The future of beauty

Forecasts of a post-pandemic beauty boom are already underway. Former CEO of cosmetics giant L’Oreal, Jean Paul Agon, has predicted a swing towards decadence reminiscent of the Roaring Twenties, which followed the 1918 global influenza outbreak. “Putting on lipstick again will be a symbol of returning to life,” he told investors in February, according to the Financial Times.

In 2018 and 2019, the industry experienced its highest level of growth. Over the past three years, Selena Gomez, Alicia Keys, Rihanna, Victoria Beckham, Emma Chamberlain, Kylie Jenner and Pharrell have all launched either beauty or skin care lines.

According to Molvar, a former editor at Allure and Self magazines, what we are now seeing is nothing short of a revolution.

“Usually beauty trends and ideals take centuries to change. And the change comes so slowly,” she said. “But with the digitalization and the globalization of the world, we’ve been exposed to so many fresh ideas, thoughts and points of view, the whole notion of what beauty is has just completely blown up.”

Expectations around time-honored taboos – from wrinkles, aging and body odor, to perceptions of women’s body hair – are changing.

“You can see it with the young folk,” Molvar said. “They’re questioning everything, like, ‘Why do we need to shave our legs? That’s an annoying habit. Why would we do that?’

“Gen Z have a good way of making us question these things that we’ve been doing forever.”

Billie, the grooming start-up selling artfully packaged razor kits, has raised $35 million in seed funding since 2017 after its depictions of women’s body hair went against the grain. In 2019, the company claimed its “Project Body Hair” campaign featured the first razor ads ever to show female fuzz.

Elsewhere in the beauty space, makeup has become a tool that belongs to both genders. Luxury giants Tom Ford and Chanel have both helped bring male makeup to the mainstream by launching men’s beauty lines in 2013 and 2018 respectively. By 2024, the male grooming market is estimated to be worth $81.2 billion.

Molvar is quick to note the increasing overlap between beauty, wellness and even the self-care movement. But as the industry expands and the demand for new products increases, people around the over have been adopting new practices – and attracting criticisms of cultural appropriation along the way.

Lately, brands are facing reproval for the commercialization of “gua sha” – an ancient Chinese treatment that uses a bian stone scraper to alleviate muscle pain and stimulate blood circulation. Hoping to cash in on the West’s new appetite for this technique, more and more companies are making their own bian stone tools – rebranding them ambiguously as “facial sculptors” or incorrectly as “gua sha“s.

Molvar agrees that for consumers, as well as brands, the line between appropriation and appreciation is ever-narrowing in the age of the internet.

“We’re exposed to a lot more ideas and fresher points of view,” she said. “If (consumers) want to practice those rituals from different parts of the world, (they) should take the time to understand where the practice came from, what it means (and) what the intention is behind it.

“But that also does not negate the benefits of (the ritual). I do think that these authentic (beauty) experiences still exist, and are very important. They should continue; we should not abandon them. But you have to be a little wary of what you’re being sold.”

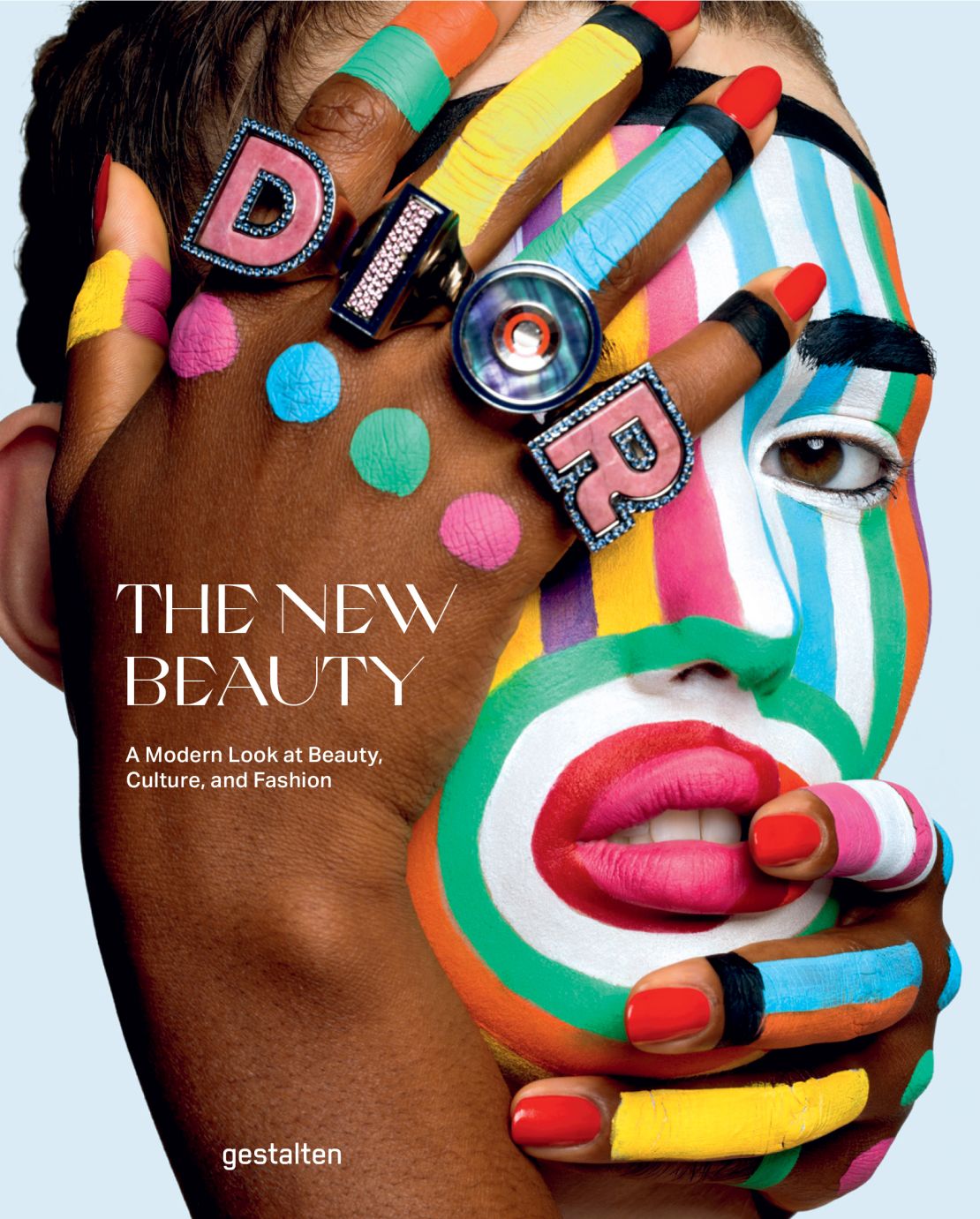

Top image: a portrait of model and actor Amber Rowan, who developed alopecia as a teenager. Shot by photographer Thea Caroline Sneve L?vstad. “The New Beauty” by Kari Molvar is published by gestalten.