Editor’s Note: Sean Redmond is one of the curators of the Morbis Artis: Diseases of the Arts exhibition. Darrin Sean Verhagen works for RMIT University. He has previously received funding from the Australia Council, Arts Victoria and City of Melbourne.

There is science in art – the alchemy of paint, the binary codes computing away in a camera, the expressive anatomy in portraiture and sculpture.

There is art in science – the artistic precision of the scalpel, the cool aesthetics of the laboratory, and the intimate observations undertaken by scientists to discover new materials and microbes living unseen in the world.

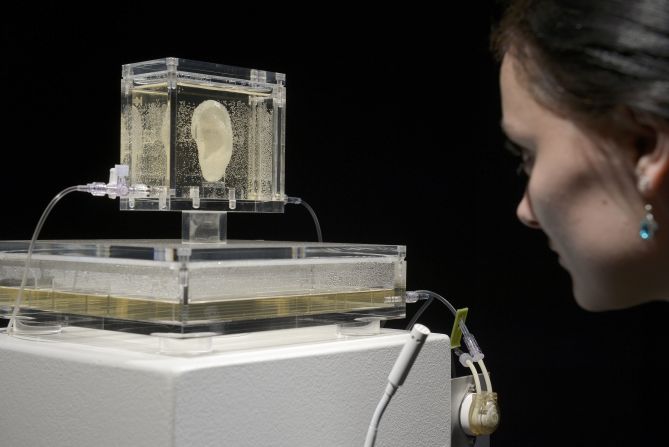

Bio-art, an artistic genre that took hold in the 1980s, solidifies, extends and enriches this organic relationship. According to the artist and writer Frances Stracey, it represents: “a crossover of art and the biological sciences, with living matter, such as genes, cells or animals, as its new media.”

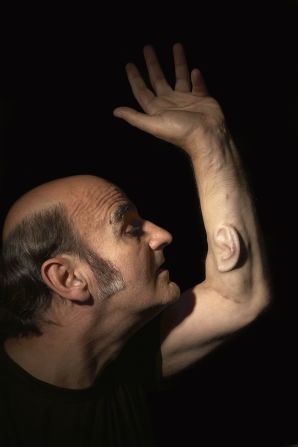

Bio-artists might use and incorporate imaging technologies within the artistic space; bringing living and dead matter into the gallery. They draw upon biology metaphors to imbue artwork with healing and wounding propensities.

In BioCouture, for example, fashion, art, and biology are weaved together, blossoming new materials into existence. As author Suzanne Anker has noted, “Donna Franklin and Gary Cass have invented dresses made from cellulose generated by bacteria from red wine.

Suzanne Lee composes ‘growing’ textiles produced by sugar, tea and bacteria to fashion jackets and kimonos.” Lee makes jackets out of cellulose produced by bacteria in baths of green tea and sugar.

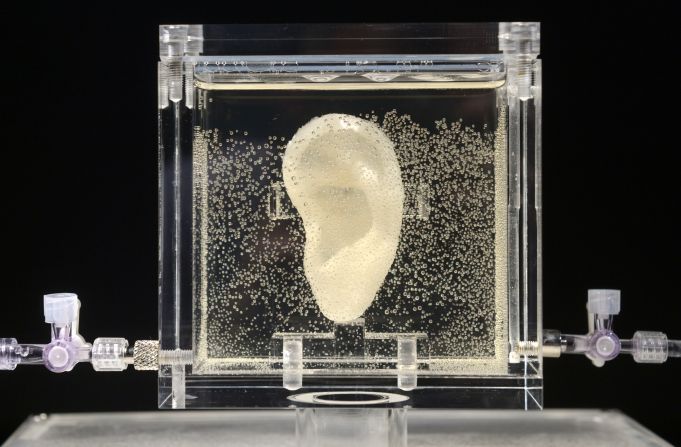

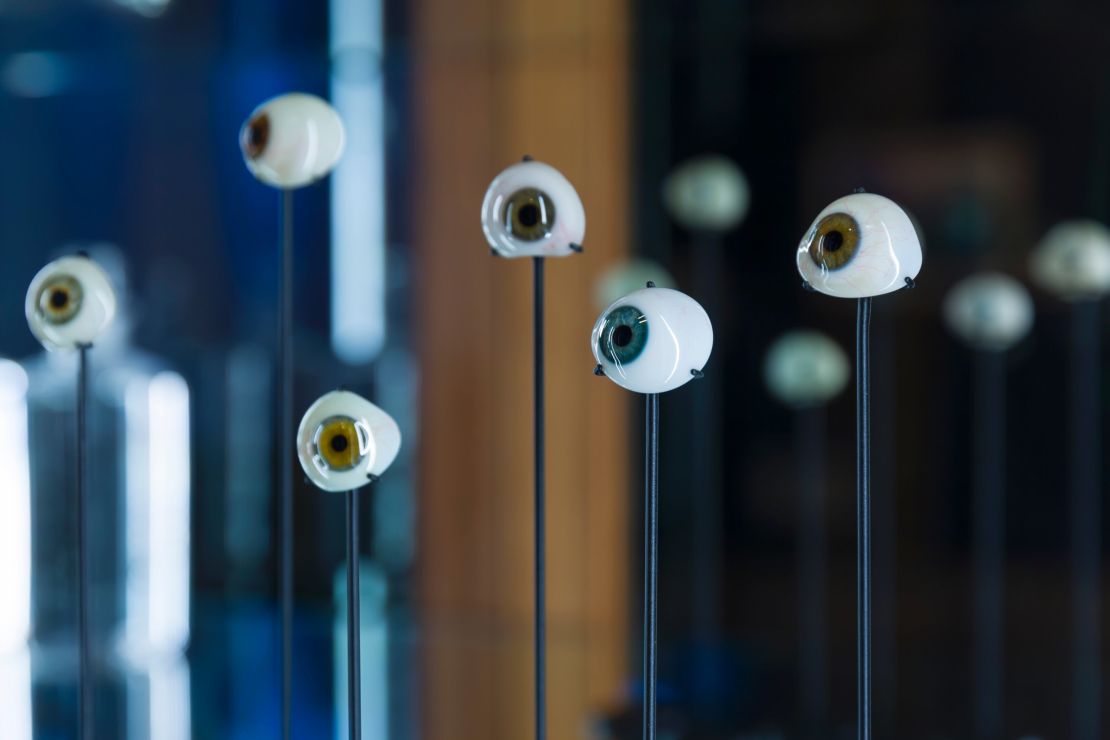

Bio-art includes the skins and cells of celluloid and digital video, the membranes of sound, and the liquids and fluids of body parts and eyeballs.

To take another example, in Christian B?k’s The Xenotext, a “chemical alphabet” is used to translate poetry into sequences of DNA for subsequent implantation into the genome of a bacterium.

When translated into a gene and then integrated into the cell, the poetry constitutes a set of instructions, all of which cause the organism to manufacture a viable, benign protein in response.

Writes B?k: “I am, in effect, engineering a life-form so that it becomes not only a durable archive for storing a poem, but also an operant machine for writing a poem —one that can persist on the planet until the sun itself explodes…”

Scientists and artists work together in what become teeming new spaces of co-creation. Together, they often set Bio-art within current debates and concerns about what constitutes life, what counts as a sentient being, and who gets to determine what lives are saved, exploited or destroyed.

Bio-art draws together the hopes and concerns of scientists and artists as we hurtle into an age where human life and everyday living seems to be undergoing radical and sometimes dangerous transformations. As author Sheel Patel suggests in relation to Bok’s work: “If a living cell can be cultured to spit out and produce novel poetry, could we eventually live in a society where humans are no longer needed to produce new thoughts, and works of literature?”

Arts and disease

In the interactive art-science exhibition Morbis Artis: Diseases of the Arts, actual and metaphoric communicative diseases are employed to explore the often toxic relationship between human and non-human life.

The exhibition explores the thin doorway that exists between life and death in a vexing age of species and habitat destruction, and the increasingly permeable tissues of contemporary bodies.

The discourses of science in particular train us to see and to look for disease in every location. Science’s microscopic and bio-technological powers allow it to reach into every atom.

Of course, dominant discourse also communes that some spaces, things, and objects are more diseased than others. We are taught to see disease in the homes of outsiders and the nests of insects, in the fabric of pariah nation states and the tissues of certain religions and philosophies.

At the same time, new materialism and animal philosophy question the very parameters of what life is, where it can be found, and they turn the question of disease onto humankind, whose activities are seen to infect all that it touches and taints.

There is a frightening collision, then, between the possibilities and limitations of human and non-human life: caught as it were between nightmare and dream.

Morbis Artis: Diseases of the Arts is composed of 11 artistic works, with each piece using a different media or art form to explore the chaos of the world it draws upon. Each artist imagines disease differently, and yet within the terror of their imaginings there is great beauty, and much hope.

In Drew Berry’s video projection, infectious cells are “set free” so that the very connective tissue of the exhibition room teems with the droplets of life and death. Herpes, influenza, HIV, polio and smallpox bacteria are projected onto the gallery wall as if they have taken flight. Magnified and chaotic, those entering the space are hit by their scale and size.

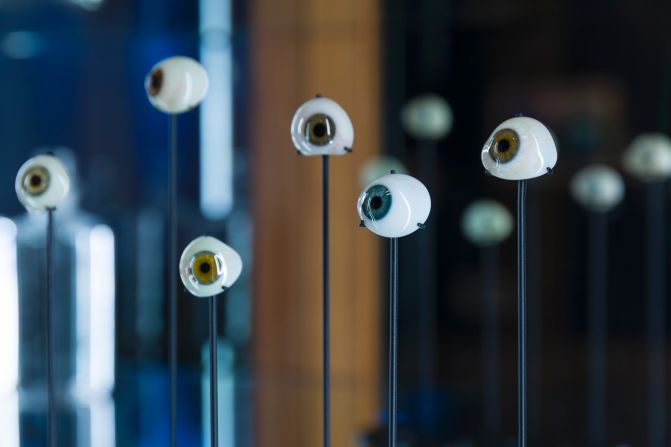

Lienors Torre’s multimedia and glass work on degenerative vision explores how our view of the world is metered and tainted by digital technologies. We see two large glass eyeballs, a liquid animation, and a glass cabinet full of jars filled with water in varying degrees of opacity, with engraved eye images on them. Eyes quickly become raindrops as the liquidity of vision is brought to watery life. There are tears and scars that reflect across the eyes of this exquisite art-piece.

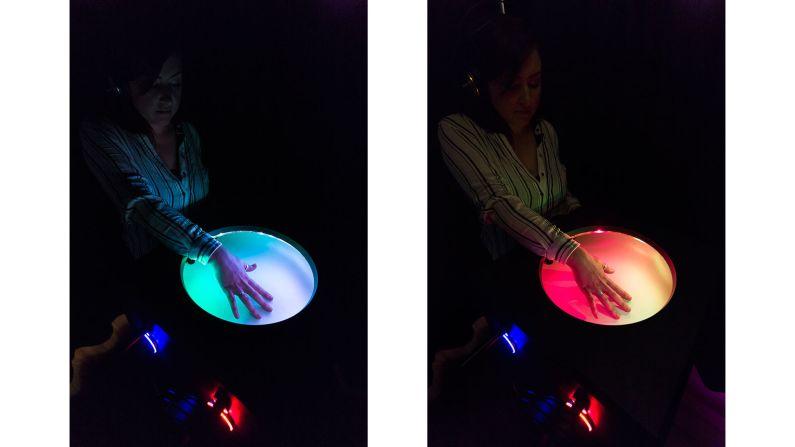

In Alison Bennett’s touch-based screen work, the viewer is presented with a high-resolution scan of bruised skin. Viewers can use the touch-screen to manipulate the soft and damaged tissue before them, and their eyes become organs of touch. What does it feel like to touch a bruise and be bruised?

The gallery is thus, both laboratory and studio. In all its variant forms, and with a scalpel and a paintbrush to hand, Bio-art fashions the world anew.

Morbis Artis: Diseases of the Arts is currently exhibited at the RMIT Gallery until February 18, 2017.

Republished under a Creative Commons license from The Conversation.