Editor’s Note: This story is part of CNN Style’s ongoing project, The September Issues: A thought-provoking hub for conversations about fashion’s impact on people and the planet.

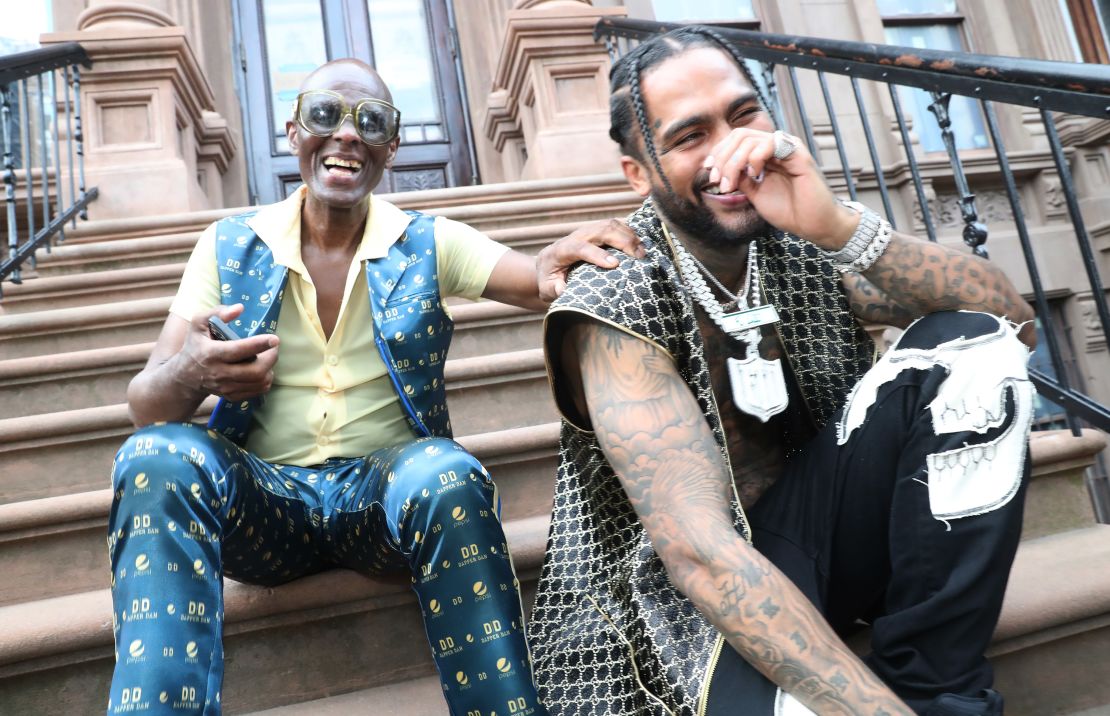

At 77, Daniel Day has plenty to be proud of. During the 1980s and early ’90s, the designer became an early icon of high-end streetwear , designing custom pieces for hustlers, athletes, and rappers from his now legendary Harlem shop, Dapper Dan’s Boutique, in New York. His use of furs, leathers, and fine fabrics screamed status for a new type of monied shopper. But the real draw was Day’s inventive and illicit incorporation of luxury logos, screen-printed onto the kind of fashion that none of the European houses were yet in the business of producing themselves.

Created in collaboration with clients from his community of friends and contemporaries, Day adopted unlicensed Fendi for Mike Tyson; crafted a jacket emblazoned with interlocking Gucci G’s for LL Cool J; and fashioned a fur bomber featuring the Louis Vuittton-monogrammed sleeves for Olympic gold medalist Diane Dixon. His designs laid the groundwork for the brand-backed logo-mania that started building around the turn of the millennium, and has seen a recent resurgence.

And yet when the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) revealed earlier this month that Day would be the recipient of this year’s Geoffrey Beene Lifetime Achievement Award, even he was a little stunned. “My aspirations for myself, in any endeavor, are as high as I think anybody who’s ever lived on this planet,” he said in a phone interview following the announcement. “Now, if you asked me specifically, about being recognized by organizations like (the CFDA), I think that would have been pretty far removed from my past thought patterns.”

Day’s surprise is understandable: It’s only recently that he’s been recognized by the mainstream fashion establishment at all – in a positive light, anyway. In 1992, after years of raids on his boutique and litigation from many of the luxury brands he knocked off, Day shuttered his business. (If Day’s supporters saw his trademark infringement as sartorial remixing, akin to the use of sampling in hip-hop, the brands themselves were less understanding.) For the next 25 years, he operated on the fashion fringes, creating pieces for clients like Floyd Mayweather, Sean “Diddy” Combs, and others in the know.

It was only in 2017, when – in a twist – Gucci creative director Alessandro Michele copied Day’s monogrammed design for Dixon for the brand’s 2018 Cruise collection, that he was thrust into the spotlight. Following calls on social media to credit Dapper Dan for the design and widespread reporting in the press, Gucci clarified that the jacket had been intended as an homage all along, and immediately extended an offer to Day to collaborate. Later that year, Gucci funded the opening of the multi-million-dollar, by-appointment-only Dapper Dan atelier in Harlem, and the brand released a capsule collection with Day in 2018.

Day is the first Black designer to be recognized with the CFDA Lifetime Achievement honor, which has previously been bestowed upon household names including Tommy Hilfiger, Vera Wang, Michael Kors, and Calvin Klein; as well as the first designer to have won without ever having staged a fashion show or sold a traditional collection.

With the decision, ??the CFDA is also acknowledging a designer who has long stood by a “for us, by us” mentality, prioritizing his relationship with his community above all else: “I consider myself 100% community… You see me on the bus; you see me on the train, you see me walking the streets of Harlem. I do not create from myself; I create from the people that I come in contact with,” Day said. “I’m not trying to dictate fashion; I’m trying to translate culture and elevate culture.

“To be recognized globally, that was a super plus, but I started out with my community.”

This attitude seems especially current: Since the dawn of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013 and the rise of social media, which has provided new means for self-promotion unregulated by industry gatekeepers, a new generation of Black designers has emerged on the global fashion stage. And many of the most successful players have placed Blackness at the core of their brand identity, centering their collections on culturally specific stories, collaborating with other Black creatives, and launching social initiatives intended to support, educate, and inspire their communities.

‘We’re here and we have something to say’

In the United States, Pyer Moss, helmed by Haitian American designer Kerby Jean-Raymond, who recently presented a series of garments inspired by everyday objects created by Black inventors during his first couture show in July, often holds open castings for amateur talent of all ages to model in his brand’s campaigns, and provided $50,000 in funding for minority- and women-owned small creative businesses at the start of the pandemic.

Across the pond, British Jamaican designer Grace Wales Bonner has produced collections, zines, photographic series, and a celebrated exhibition that draw on different facets of the African diaspora. Thebe Magugu, the Johannesburg-based winner of the prestigious 2019 LVMH Prize for emerging designers, has impressed critics with collections and short films that highlight both traditional craftsmanship, and lesser known narratives of African history and modern life. (For his Spring-Summer 2021 collection, he interviewed female spies who undermined South Africa’s apartheid-era government.)

While injecting the industry with diverse references and viewpoints, these emerging designers are also challenging industry standards about representation and storytelling. “(A lot of) these brands are also critiquing the industry – though it’s not always in your face – through their design aesthetic, or their design sensibilities,” said Rikki Byrd, a Chicago-based researcher and curator focusing on the intersection of fashion and race. “They’re not just saying, ‘We’re here because, of course, we deserve to be.’ No, we’re here and we have something to say.”

But where designers of old may have worked on the sidelines of a White-centric industry in relative obscurity, these younger talents have claimed center stage, blowing up on social media, fronting glossy magazines, and picking up major awards. Two of the CFDA’s 2021 nominees for American Emerging Designer of the Year – Edvin Thompson of Theophilio, and Jameel Mohammed of Khiry – have made Black heritage, storytelling and community core to their company missions.

These efforts can be seen as a direct inversion of the cultural appropriation – the controversial and uncredited co-opting of cultural elements – that has plagued the industry for decades. Writing presciently in the 2012 anthology “Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness,” journalist Michaela Angela Davis summed it up: “We have finally made it to a generation that is bad and safe enough to holla and buck back if you try to take any more of our genius stuff. We are socially and intellectually armed and prepared to claim and defend our ancestral intangible jewels.”

Building on legacy

But while the mainstream recognition of such efforts may be new, the ethos it’s rewarding is not. “These (designers) are part of a larger, longer genealogy of African and African diasporic designers who have been using their fashion as political art, as cultural artifacts of their heritage and their roots,” said Tanisha C. Ford, a professor of history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and author of “Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul.”

Decades before Dapper Dan was offering premium bootlegs in Harlem, the fight for civil rights and the Black is Beautiful movement led to a rise in Afrocentric Black designers across America and elsewhere in the diaspora. In the late 1960s, PBS and LIFE magazine reported on the success of The New Breed, a Harlem-based shop and manufacturer of dashikis and other garments that doubled as a hub for Black activists, politicians, celebrities (James Brown and Sammy Davis Jr. were supporters), and ordinary members of the community.

By this point, a similar spirit had already spread through the African continent, as nations gradually emerged from colonial rule. “If you take a look at African-based publications in the 1940s, and ’50s, you can see how much of that conversation was linked to having pride in our own,” Ford explained. “The magazines became a place where they highlighted designers from Tanzania, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Lesotho. (Those magazines) were being circulated broadly then, but because we don’t have access to those magazines in the same way, a lot of that rich history is lost.”

In the ’90s, Byrd said, this attitude of self-determination and celebration took on new form with the rise urbanwear brands like FUBU (“For Us, By Us”), Rocawear, Sean Jean, and Karl Kani, that turned the uniforms of hip-hop culture into a product that would eventually be found in department stores across the nation.

“Here are Black entrepreneurs who have an affinity for fashion and a particular understanding about industry in general… They’re well aware of the fact that (the mainstream fashion industry) doesn’t want us here, and when they do want us here, they want to own their terms,” Byrd said. At the time, many White-owned brands happily accepted the free publicity that came with having hip-hop artists wearing their clothing, but chose not to collaborate with them directly.

“What I find with the urbanwear brands is that they too were taking the style from the streets, but the streets that they knew, the streets they walked down every single day, the streets where they connected with their peers,” Byrd said. “I do think part of it was, of course, (Black-owned brands saying) ‘We want to be successful in the fashion industry. We just want to be able to do it our way; we want to be able to have control over it.’”

More than a trend

In the high fashion space in which many of today’s most talked-about Black designers operate, however, highlighting race hasn’t always been a priority. While early breakthrough designers such as Patrick Kelly and Willi Smith – the subject of an upcoming exhibition at the de Young Museum, and an ongoing show at the Cooper Hewitt respectively – were both open about the influence of their upbringings on their design aesthetics (Kelly’s logo was a smiling Golliwog), neither explicitly designed with racial narratives in mind.

Often, though, centering a brand on race could be seen as a hindrance rather than a benefit. “There were so many times where Black designers would present a lookbook with all black models, and they would be challenged on that – but if it was all White models, no one would challenge it,” said Brandice Daniels, founder of Harlem Fashion Row, a platform that supports emerging designers of color. “There are so many designers that wouldn’t put their headshots on their websites because they thought that buyers wouldn’t pick them up, and there was truth to that.”

Last spring, Mohammed, who positions his label Khiry as an “Afrofuturist luxury brand,” debuted an abstract campaign video that juxtaposed glamorous brand imagery with scenes of Black beauty, resistance, and mundanity, as well as pain and oppression. “I want to be participating in this kind of image war, and inject some imagery that’s going to frame Black culture as aspirational, but I’m also interested in explaining to the culture why future support for Black causes will be necessary by contextualizing where we are historically,” he said.

For Mohammed, the film highlighted the tensions between his personal politics and the compromises required for success. Alienating consumers who bristle at his messaging, he acknowledges, is always a possibility, but it’s a risk he’s willing to take. “The society that can produce (the campaign video) as a luxury advertisement and buy into the ideals that it ascribes is the society that I want to live in. As an entrepreneur, I hope that we’re living there. As an artist, I recognize that this has always been kind of a speculative project, and that, in a way, this might be my own little self-sabotaging impulse.”

Daniels believes young designers championing Blackness and their communities have reason to be optimistic – and not just because of awards and industry opportunities. “??At the end of the day, people are still so attracted to authenticity, and authenticity is something that is rare today,” she says.

“I think (shoppers today) have higher expectations of what they are buying into, and I mean buying into both on a literal level – what they’re spending their dollars on – and from an experiential perspective. Am I buying into an idea? Am I buying into a community? Am I buying into something that supports my values as a consumer?” Byrd added. “As a consumer, or a person in the world, I’m not making those decisions every single time I do something, but I’m actively thinking about it.”

Ford, Byrd, and Daniels each expressed concern that the current vogue for brands that foreground Blackness will disappear if conversations around the fashion’s systemic inequality fade. This, Byrd points out, can have real consequences when so many young brands rely on sustained investor funding and institutional support to stay afloat. However, Ford believes that, regardless of the long-term outcomes, such culture-focused storytelling is crucial to enriching individual communities and furthering broader conversations and race and representation in fashion.

“Quite frankly, we don’t know how long this will last, but for the time being the media is hungry for new narratives,” she said. “Why would we ever want to rely upon someone other than ourselves to tell our story? To use our aesthetic practices to make the clothes that we feel compelled to make?

“If we’re truly in the business of being unapologetic, then you have to take the risk.”

Heartened by the work of young designers like Pyer Moss’ Jean-Raymond (“He can make a difference”), and the belated credit being given to Black designers like himself, Day believes the fashion industry at large can only stand to benefit from the platforming of these new, outspoken voices.

“To me, fashion, without messaging is like a container of milk with no milk in it,” he said. “The diversity within the Black and Brown community is so enormous. If everybody uses their skills to tell their stories, I think a fascinating world will emerge.”

Top image: Models walk the runway for the Pyer Moss Spring-Summer 2019 show.