Editor’s Note: The following is an extract from Bubbletecture: Inflatable Architecture and Design, by Sharon Francis, published by Phaidon

Bouncy castles and pool floats might be the populist face of blow-up objects, but the world of inflatables is far richer.

Innovative, revolutionary and often avant-garde, inflatable structures are, by their very nature, an expression of advancement – a reimagining of traditional forms. Influential in aviation for more than two centuries, this deceptively simple technology has been at the forefront of architectural movements in recent decades, enabling cutting-edge artistic practice and symbolizing technological utopianism.

Today, “bubbletecture” can be seen in structures as transient as the Big Air Package – an art installation that, for moments, was the largest self-supporting inflatable envelope in the world – and as enduring as the domes of Britain’s Eden Project. With ground-breaking new materials and techniques, blow-up architecture could soon make the Moon or Mars our home.

The journey so far has been filled with radical experiments whose potential remains only partly fulfilled.

The first inflatable, the hot-air balloon, was invented in 18th-century Paris, then the cultural epicenter of “The Enlightenment.” French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-étienne Montgolfier created that first balloon in 1782 by burning straw and wool to heat air under a large, lightweight paper and fabric bag.

A year later, the first manned, untethered flight sailed over Paris for about 15 minutes. It would be more than 150 years – following the Zeppelin’s rise and dramatic fall in the Hindenburg disaster of 1937 – before the inflatable came down to Earth during the Second World War.

The birth of bubbletecture

On the battlefields of Europe, the US 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as the Ghost Army, staged more than 20 mass deceptions using inflatable tanks and powerful amplifiers to create the impression that the Allied forces were more powerful than they actually were.

Far away, equally ingenious inventions were unfolding, as the first basic inflatable structures were being created by American engineer Walter Bird.

Initially created for the US military, his “radomes” – structural, weatherproof enclosures – were used to protect radar antennae. In the years after the war, Bird developed inflatables including storage sheds, greenhouses and pool enclosures.

Among a series of collaborations with leading architects, he worked with legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the late 1950s, who was then taking a break from overseeing the construction of The Guggenheim in New York City. Their prototype inflatable village of “Fiberthin Air Houses,” intended as affordable homes, were constructed from vinyl-coated nylon fabric and supported by low-pressure air from a fan-driven heating and cooling system.

With the arrival of the sixties, cheap, mass-produced plastic became widely available and young, radical architecture groups embraced the creative potential of inflatable technology.

Archigram’s wildly imaginative “Cushicle” and “Suitaloon” projects, designed in 1964 and 1967 respectively, proposed a new relationship between the individual and the city – the suits, when inflated, enabled people to carry a complete environment on their body.

Ahead of its time in considering ecological issues, in the early 1970s, architecture group Ant Farm proposed a “Clean Air Pod” that was inexpensive, transportable and almost instantaneous, while Spatial Effects was experimenting with its “Waterwalk” series of buoyant inflatables.

Bubbletecture today

While simple inflated structures with a single membrane remain in the domain of temporary architecture, various double-walled membranes have become part of more permanent building systems.

Among these are panels made from ETFE (ethylene tetrafluoroethylene). A fluorine-based plastic, it is durable, recyclable, highly transparent, corrosion-resistant and very lightweight in comparison to glass structures.

Its true potential was made evident in the Eden Project, designed by Grimshaw Architects in 1998. The Allianz Arena by architecture firm Herzog & De Meuron, constructed for the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, and the Water Cube, built for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, raised the profile of the technology further.

Recently, Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s adventurous new-build, The Shed in New York’s new Hudson Yards development, demonstrates the potential of bubble architecture to allow major buildings to transform. The $475 million arts center features a telescoping outer shell made from ETFE systems, which glides along rails onto an adjoining plaza to double the footprint of the building.

Inflatable products can also be immediate and inexpensive solutions in emergency situations, as shown by Michael Rakowitz’s paraSITE heated housing for the homeless.

Impressive, immediate and mobile, Ark Nova, a collaboration between architect Arata Isozaki and artist Anish Kapoor, provided a mobile performance and exhibition space to unite communities still rebuilding after the devastation caused when a major earthquake and tsunami hit Japan in 2011.

Art and awe

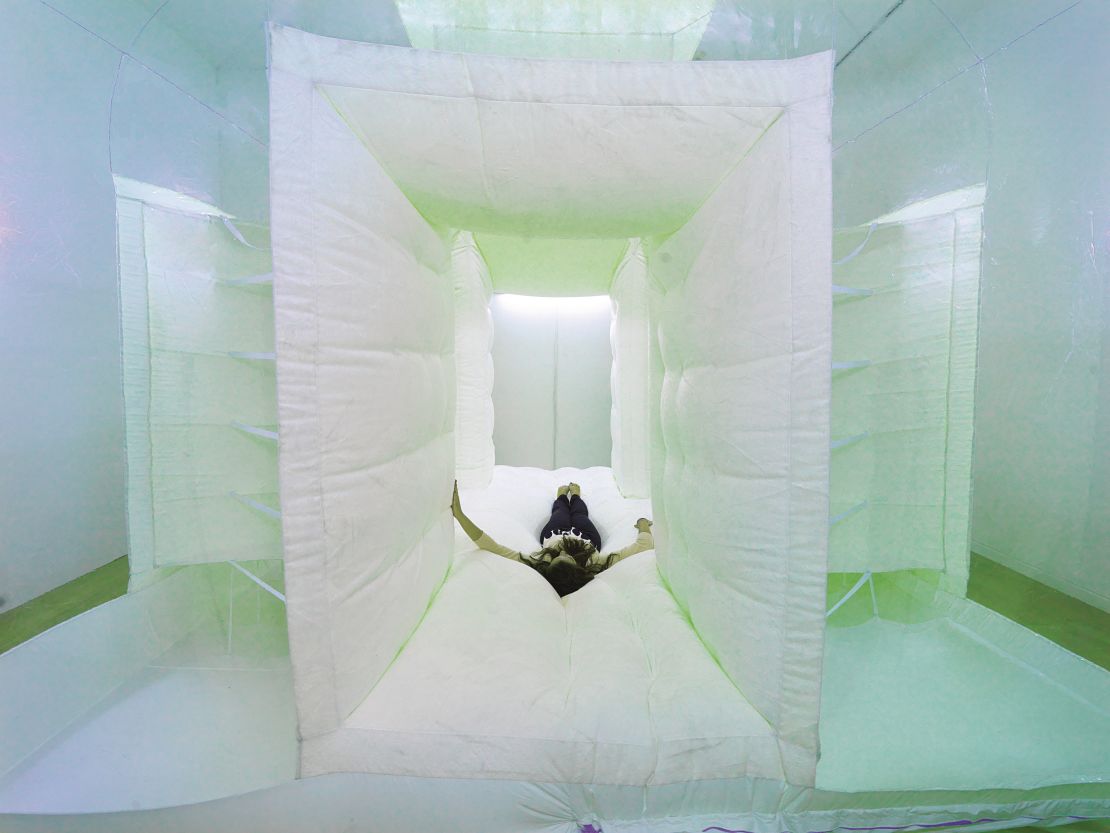

Some inflatable architecture has sought to extend the boundaries of the achievable, while at the same time generating awe and delight. Environmental artist Christo’s monumental “Big Air Package” was a thing of wonder and fragility, and the work of collective Penique Productions – such as El Claustro – seeks to articulate the architectural details of the spaces they inhabit.

The “RedBall Project” by Kurt Perschke is a series of interventions in which a giant sphere is wedged and squeezed into various architectural contexts, altering perceptions of the built environment through humor and surprise.

Plastique Fantastique’s “Sound of Light” utilized technology to capture light waves, translating them to sound waves to create a unique experiential color-infused soundscape, while Osmo by Loop.pH provided a transportable projected universe of nearly 3,000 stars for city dwellers. TeamLab’s “Homogenizing and Transforming World” (top image) immersed visitors within a mass of giant, color-shifting floating spheres that communicated with each other wirelessly.

The next frontier

In a competition backed by NASA, architectural firm Foster + Partners created a conceptual, modular habitat for Mars. The proposed dwelling is constructed robotically prior to the arrival of the astronauts.

The inflatables are rapidly deployed by semi-autonomous bots and provide stability despite uneven ground conditions. 3D-printed components, made from the excavated soil and rocks, complete the construction.

NASA scientists working in collaboration with researchers from the agriculture department of the University of Arizona in Tucson, USA have developed an inflatable Martian greenhouse prototype that allows vegetables to be grown in deep space.

The possibilities for future development and use, in and beyond the digital age, have the potential to expand as new frontiers, materials and processes seek to exploit the versatile, lightweight and sustainable nature of inflatable products.

Having established itself within the domain of exploration and experimentation – from the very first steps of aviation to cutting-edge fashion – the blow-up serves to blow out traditional forms and perceptions.

Bubbletecture: Inflatable Architecture and Design, published by Phaidon, is available now.