Editor’s Note: In the latest episode of “On China” on CNN International, Kristie Lu Stout talks to the people at the forefront of the country’s heritage conservation.

Story highlights

China is struggling to protect its cultural treasures

One-third of the Great Wall has disappeared

Country's world heritage sites are threatened by factors such as tourism

Some entrepreneurs propose new ways of preserving ancient structures

China is a nation in constant fast-forward as it charts its economic and social course in the form of Five-Year Plans. But as the country powers into the future, efforts are lagging to protect its past.

Here are the grim, but conservative estimates of what’s been lost:

Since 1990, more than 1,000 acres of historic alleys and traditional courtyard homes in Beijing have been destroyed to make way for high-rises and office blocks.

In the last decade, as many as 900,000 villages in China have disappeared as rapid urbanization and unchecked development swept through the nation.

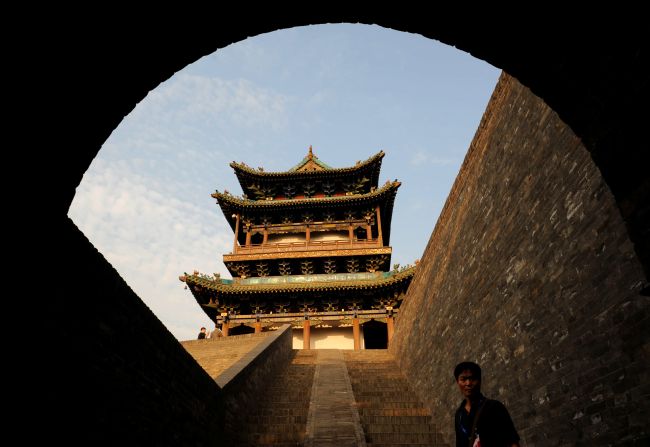

And, incredibly, about one-third of the iconic Great Wall of China has disappeared due to natural erosion and human damage.

“It’s a complicated site,” says Guanghan Li, the China program director of the Global Heritage Fund. “It’s too complicated to ensure that the preservation of all parts of the Great Wall will receive the same amount of attention.”

And so it’s come to this. Despite all its might and economic prowess, China is struggling to protect its cultural treasures including the very structure it built to fortify itself centuries ago.

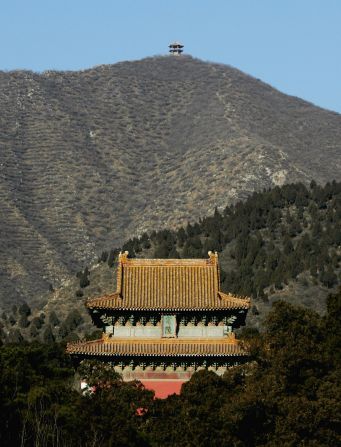

China has 48 world heritage sites, including the Great Wall. Nationally listed protected sites benefit from funding from the central government. But when it comes down to a provincial level, it’s up local governments to safeguard structures.

China’s architectural wonders are endangered

Due to a lack of accountability, and incentive, local Chinese officials are more often than not, up to the task.

“Usually the protection of cultural heritage sites would not count into the political grading [assessment] of a local official. If he cleans up the environment, he might get scores [additional points] for that, but not for protecting a historical site,” Li points out.

Thankfully, private individuals like Belgian entrepreneur Juan van Wassenhove have stepped in to launch bold efforts to help save parts of China’s past.

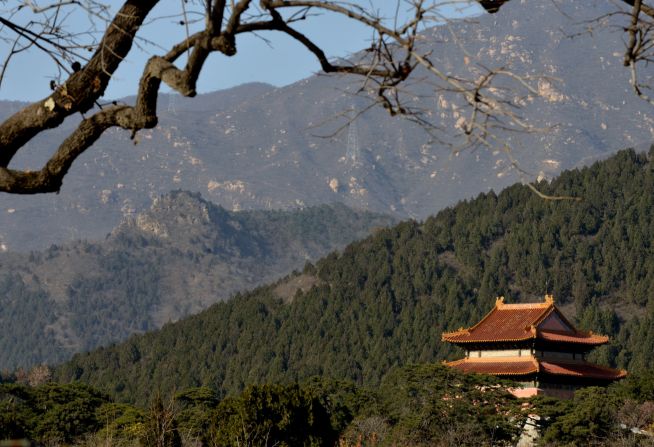

Converting a Qing Dynasty temple into a hotel

He’s the founder of Beijing’s Temple Hotel. Once a Qing Dynasty temple, it was turned into a factory by the Communist Party before falling into disrepair as an abandoned garbage sorting center.

Along with his Chinese partners one decade ago, van Wassenhove set out to rebuild and restore the historic temple complex.

“Just to clear the site took 400 trucks of debris, big trucks that you have to move out of a small alley,” van Wassenhove recounts.

“But the major battle is that the style we adopted is called [in Chinese], “xiu jiu ru jiu” – preserving the material to not erase everything and do something new. ?There was a bit of a battle for people, even among officials, to understand what we were trying to do.”

His team went out of their way to reuse original wood and tiles while consulting with the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage to ensure the temple’s authenticity.

“My vision was that in this era of very fast economic growth, wealthy Chinese would be very interested by their own heritage. It’s just a matter of time and this is more or less what happened.”

With more disposable income at hand, a rising number of Chinese are spending more to travel. In the first half of 2015, Chinese tourists took more than 2 billion domestic trips. They made 3.6 billion trips in the previous year.

As a result, some of China’s most spectacular cultural destinations are crumbling under the pressure of this surge in tourism.

China’s World Heritage sites are threatened by millions of tourists

The ancient town of Lijiang now receives some 8 million visitors a year. Despite being a UNESCO world heritage site, it’s become overwhelmed with karaoke bars and souvenir shops.

The local Naxi ethnic minority has also been crowded out, many of them renting their old homes in Lijiang’s ancient center to the tourism trade.

“They are wealthier, but are they completely happy?” asks Mei Zhang, founder of the sustainable travel company WildChina. “No, because the lifestyle and the relationships they built with their neighbors have changed.”

“This is, unfortunately, the price they are paying.”

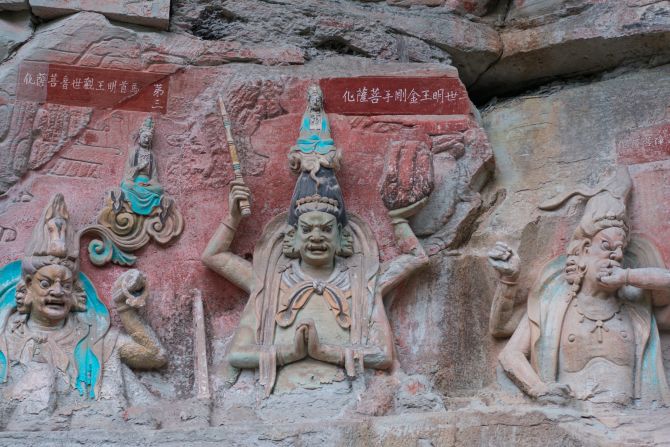

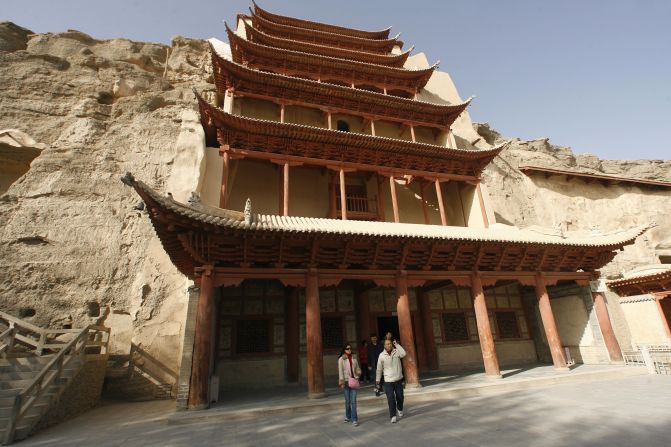

Limiting visitors to protect Buddhist caves

One radical solution to safeguard cultural sites like Lijiang is to limit visitor numbers, an approach that has helped preserve the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, a spectacular cache of Buddhist caves famous for their statues and wall paintings that date back well over a thousand years.

To protect the site’s treasures, a waitlist system was adopted to limit the number of visitors to 3,000 each day.

Chinese experts at the Dunhuang Academy also partnered with the Getty Conservation Institute to open a multi-million-dollar visitor center to enhance understanding of the grottoes while reducing foot traffic at the actual site.

?“Dunhuang is a very special case,” says Li. “China got it right because it’s actually managed by a professional research institute so their primary interest is in the conservation management of the site.”

But heritage conservation is not just about protecting the past. It’s also about the present and the future – creating living spaces that are relevant to Chinese today.

New ways forward

Back at the Temple Hotel in Beijing, years of restoration have transformed the ancient temple into an eight-room hotel and gallery with regular concerts and exhibitions, including the only James Turrell Skyspace installation in China.

The converted temple embodies core ideas of heritage conservation, by bringing people together to instill a sense of shared history, belonging, and cultural confidence.

“Cultural identity is about confidence, and when you have confidence then you can be very creative,” says van Wassenhove. “China is going to be very innovative, and I think that should come from heritage conservation.”

Thanks to such conservation work, a near-ruined temple in Beijing has new life and new relevance in today’s China. ?It’s a welcome development in a country that all too often tears down its past.

The full “On China” episode will air on CNN International on October 29 4:30am 11:30pm, October 31 12:30am 11:30am, November 21 7:30am, November 22 12:30am 11pm ET