Editor’s Note: This feature is part of a wider CNN Style series on how culture in China is evolving in the Xi Jinping era.

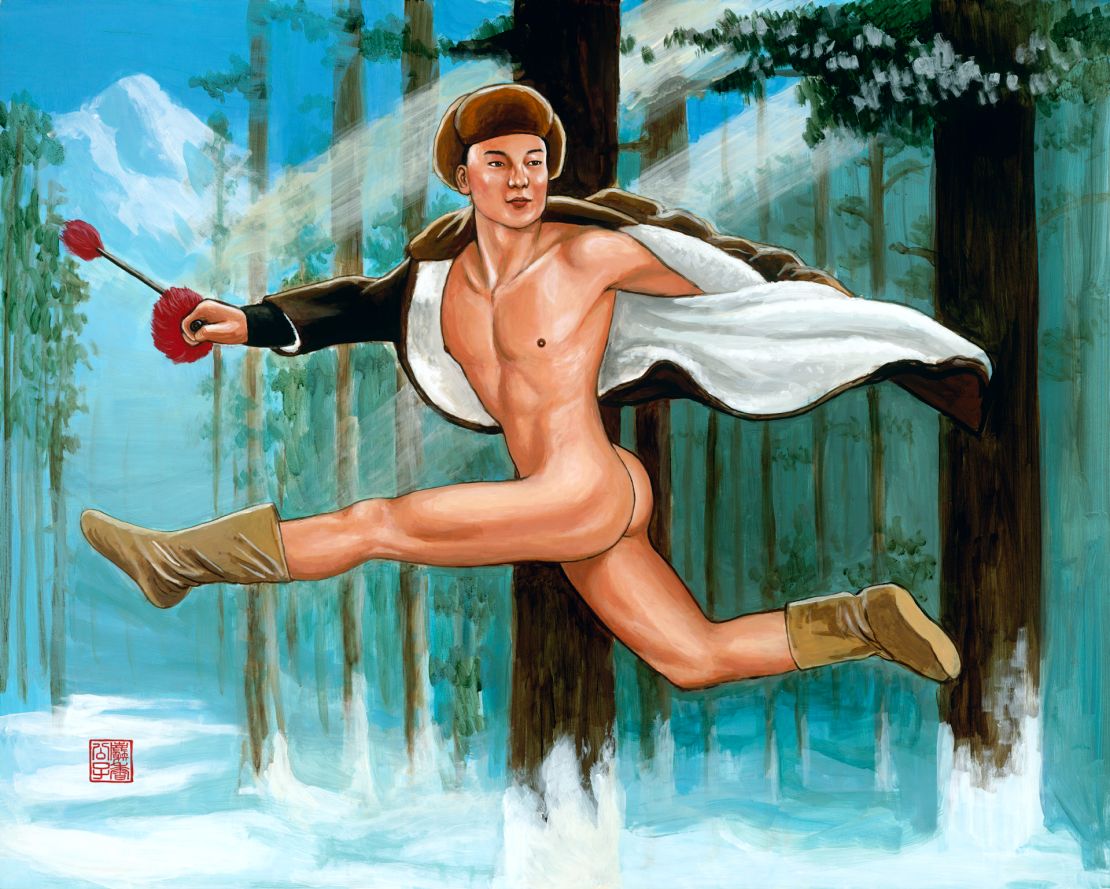

Musk Ming paints Chinese men in suggestive poses. Delicate ink-formed faces stare longingly from the paper, their lean bodies dressed in green caps with red stars. Some wear white and navy sailor hats with ribbons. Others are cloaked in olive coats with brown faux fur collars. The men may not be wearing much, but the accoutrements of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) are unmistakable.

For Ming, born and raised in China but living in Berlin since 2005, the risqué motif of homoerotic PLA soldiers came naturally.

“I paint what interests me – and from personal experience,” said the 40-year-old gay artist, who uses “Musk Ming” as a pseudonym. He grew up in a military compound in northern China and attended a Chinese naval academy before moving to Germany. “The soldiers I saw were the ideal men: young, innocent … and beautiful.”

That’s hardly how China’s strictly controlled state media described uniformed men in its recent exhaustive coverage of the country’s grand military parade, which marked the 70th anniversary of Communist rule.

On October 1, millions of Chinese viewers watched an all-powerful President Xi Jinping approvingly inspect 15,000 PLA troops – mostly young male soldiers with chiseled faces and fierce looks – as they goose-stepped through the center of Beijing, followed by columns of tanks, missiles and drones.

Underscoring the soldiers’ physical and mental toughness, adulatory news reports detailed every aspect of their selection and training for the grandiose display of Chinese military might.

The vast chasm between Ming’s work and the images shown in state media perfectly illustrates a heated debate in China about what constitutes the image of the “ideal man.”

It’s a conversation unfolding as the ruling Communist Party’s cultural czars tighten their grip over the country’s creative sector by, among much else, regulating the on-air appearances of male celebrities, from movie stars to boyband members.

Depicting masculinity in art

In discussions about masculinity in China’s heavily censored cyberspace, a consensus often emerges on the gold standard of an ideal Chinese man: the PLA soldier.

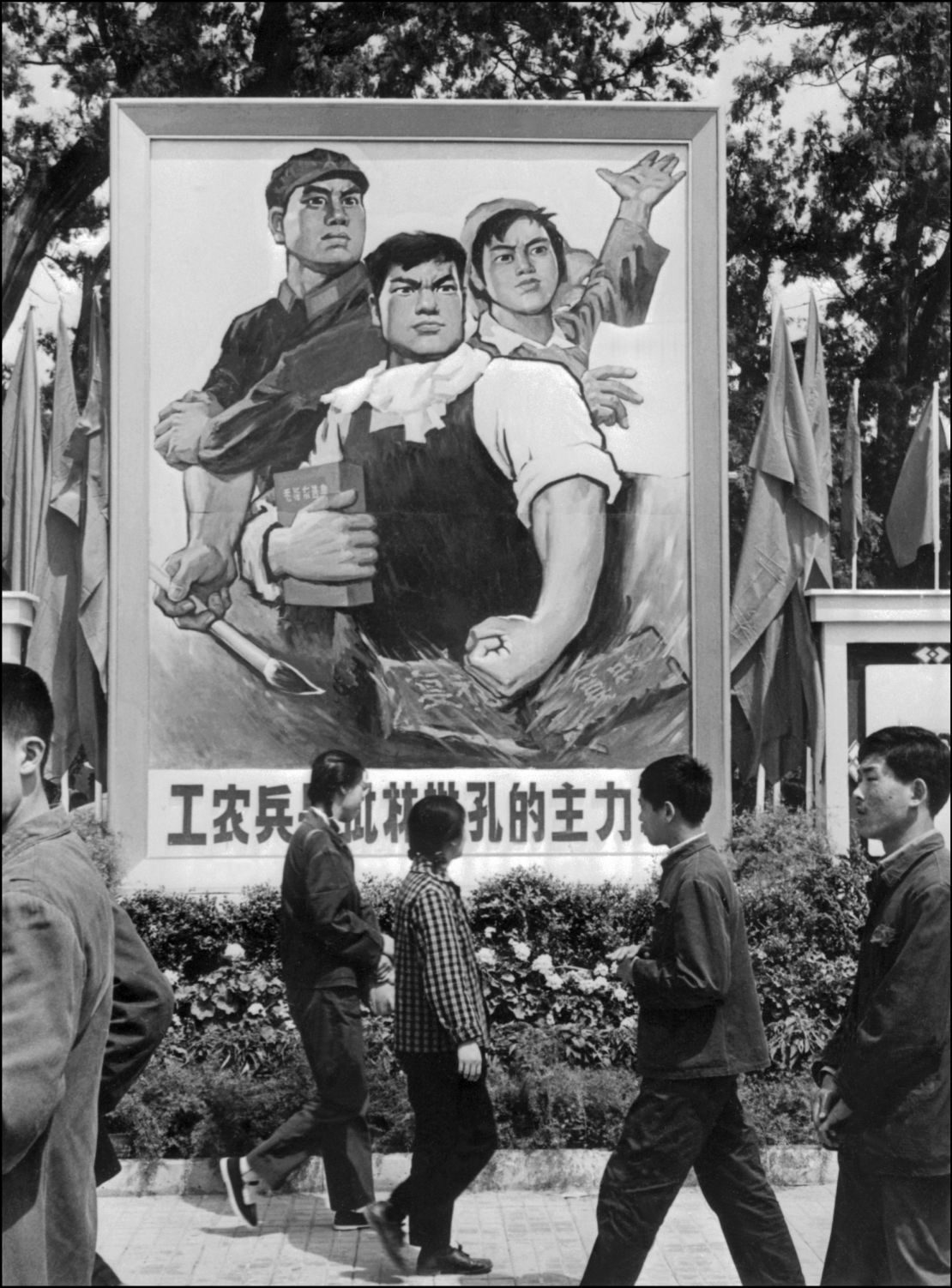

It’s a sentiment that experts say has been reflected in art throughout the history of the People’s Republic, which was founded in 1949 by Mao Zedong following the Communists’ triumph in a bloody civil war.

From vintage propaganda posters to slick new music videos, images of PLA troops have long shaped modern Chinese perceptions of masculinity. The soldiers’ strong bodies and minds are touted as the ultimate male virtues, along with their fierce loyalty to the party – qualities that some say Xi eagerly wants to promote as he vows to lead China into a great “national rejuvenation.”

For the first three decades of Communist rule, artistic depictions of Chinese men were dominated by heroic portrayals of PLA soldiers and, to a lesser degree, farmers and industrial workers – two pillars of the proletariat class.

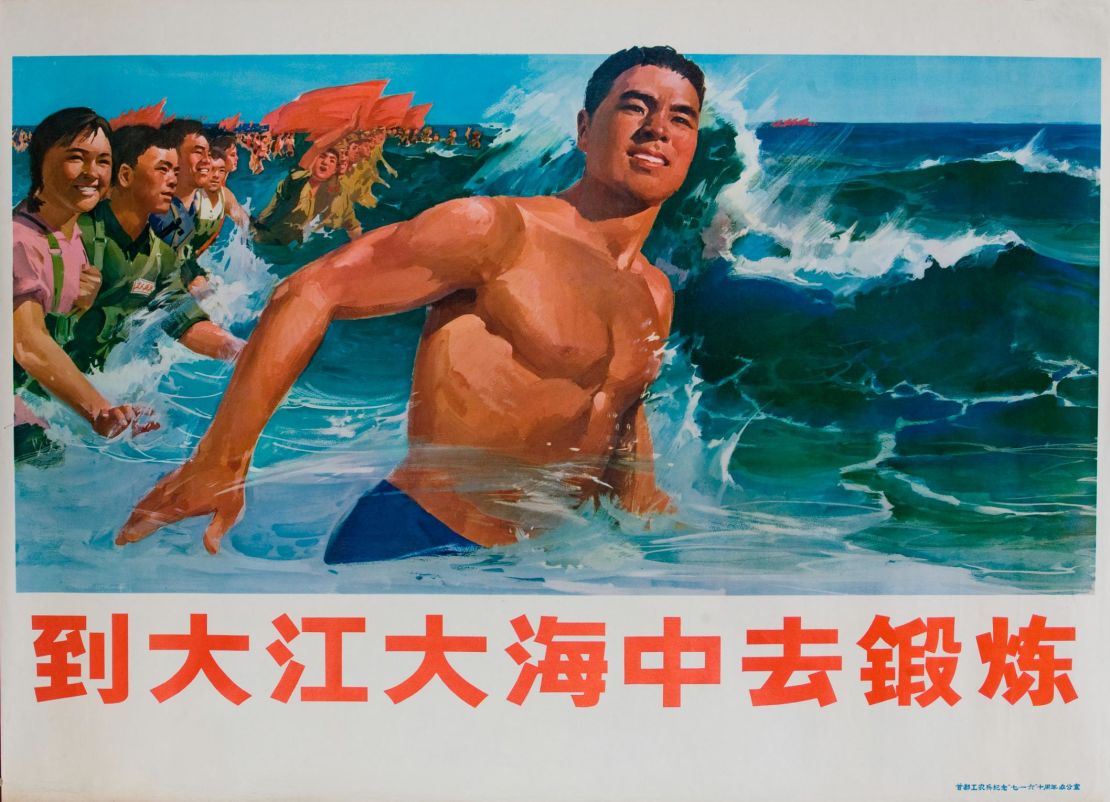

Although some of the genre’s works were created with ink, in a traditional Chinese style, the majority comprised neoclassical oil paintings or watercolors by artists who either studied overseas or were influenced by Western trends, according to You Yang, deputy director of the Beijing-based UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Neoclassical art, which traces its origin to ancient Greece and Rome though it rose to prominence in 19th-century Europe, is known to feature male protagonists with accentuated muscles striking gallant poses.

After 1949, Mao made it clear that “all artwork must reflect the leadership of the Party and the will of the state,” said You, explaining that neoclassicism found fertile ground in Communist societies – first the Soviet Union and then China – where artists used the style to fulfill their political duty of worshipping war heroes or strongman leaders.

The oil painting “Forcibly Crossing the Dadu River” is one oft-cited example in this category. Illustrating a turning point during the Red Army’s famous Long March in the 1930s, the unknown artist depicted 10 young soldiers on a small boat as they charged toward enemy fire.

Their tanned, sinewy arms in various states of motion, half of the soldiers row the vessel against rapid currents and high waves, while their comrades point their guns at the banks – a moment in time, captured before Communist troops clinched what they have since described as a miraculous victory against a bigger and better-armed enemy.

Such portrayals of male characters and historic victories reached their peak during the decade-long Cultural Revolution that Mao launched in 1966. In paintings, as well as on stage and on screen, all protagonists – who were almost always men – had to be “red and bright” to highlight their revolutionary credentials and heroism.

The result was an inevitably politicized masculinity, said You, represented by military men with sharp jawlines and muscular arms. Throwing their clenched fists into the air as they vowed to defeat the enemy, these heroes were devoid of any hint of sexuality, in line with the party’s puritanical moral code.

Mao’s death in 1976 spelled the end of the Cultural Revolution, but the now-entrenched public perception of masculinity persisted despite growing diversity in artistic depictions of men – a trend that began with the display of male subjects in more vulnerable emotional states, ranging from angst to melancholy.

‘Little fresh meat’

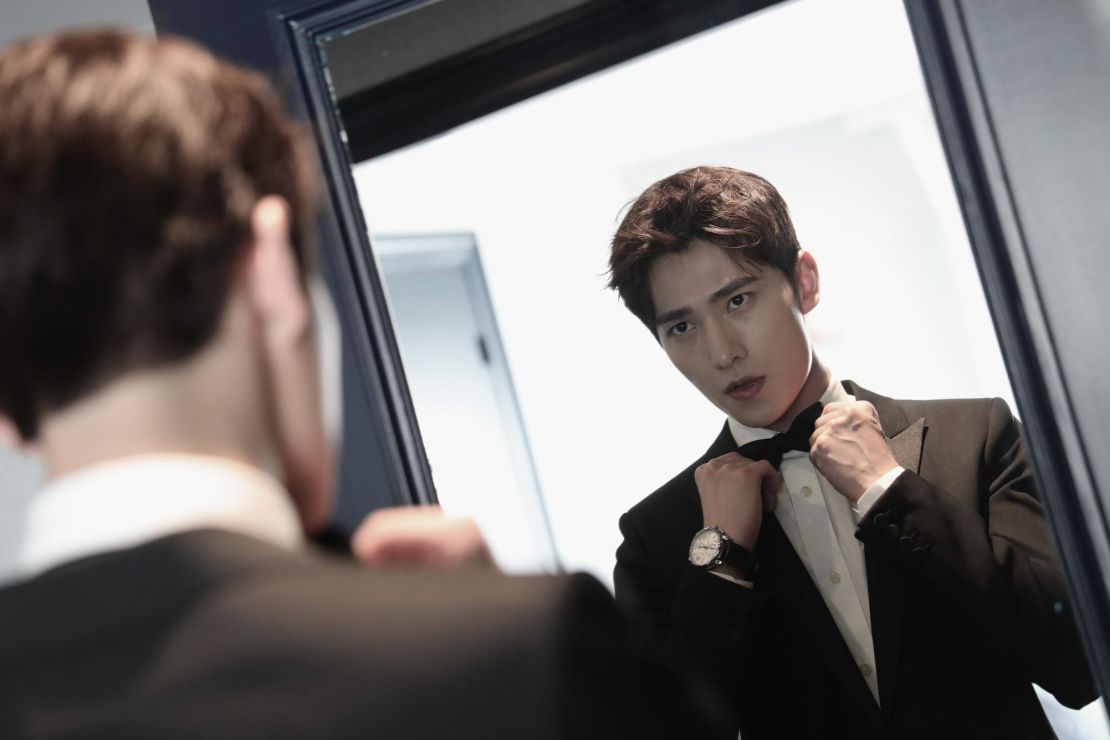

In a country now boasting more than 800 million internet users, the ideal aesthetics of the PLA soldier are being challenged by a new generation that increasingly looks to young celebrities – and their social media presence – for cues on what it means to be a man.

This includes some of the country’s most bankable young entertainers, including singer-actor Lu Han, who appeared alongside Matt Damon in the 2016 action film “The Great Wall” and has more than 60 million followers on Chinese social media platform Weibo, and boyband TFBoys, three teenage heartthrobs estimated by local media to be multi-millionaires.

Dubbed “little fresh meat” by domestic media for their boyish features and popularity, many of today’s young male celebrities put on makeup, dye their hair bright colors, accessorize and sport androgynous clothing. Like South Korean K-pop stars, they boast slender figures and often wear cutesy expressions.

In a report released early this year, the online shopping platform of Chinese tech giant Alibaba found sales of men’s cosmetic products jumped more than 50% in 2018, naming the popularity of “pretty boys” as a reason.

But after a period of social liberalization in the post-Mao era, there are signs that Xi’s government is beginning to turn against male role models deemed too effeminate. A widely cited commentary, published last year by state-run Xinhua news agency, said: “Whether a country embraces or rejects (effeminate men) is … a grave matter that affects the nation’s future.”

Focusing its ire on wildly popular male idols, the article blasted the “sickly aesthetics” that had propelled “gender-ambiguous, heavily made-up, tall and delicate” young men to stardom on television and online.

“The phenomenon of ‘sissy men’ has caused a public backlash because the impact of such sickly culture on the youth cannot be underestimated,” it said.

“When critics say ‘sissy young men turn a nation sissy,’ they may sound somewhat facetious,” it added. “(But) nurturing a new generation that could rejuvenate the nation requires the resistance of erosive unhealthy culture.”?

Following Xinhua’s lead, other Chinese media outlets have published blistering editorials and commentaries criticizing male celebrities who appear effeminate.

There have also been user-generated online campaigns calling for some celebrities to be banished from the country’s airwaves and internet platforms because of how they look. The government also seems to be tightening restrictions on what is seen on screen.

Earlier this year, China’s major video-streaming platforms began censoring male actors’ earrings, blurring their earlobes. Incidentally, the ban came after censors prohibited the depiction of same-sex relationships on television and online, along with a wide range of what China calls “vulgar, immoral and unhealthy content” that also includes incest and one-night stands.

Some targeted celebrities, including TFBoys, have responded to critics by ditching cosmetics and flowery wardrobes in favor of showing toned muscles in photo shoots.

Another trend has been the launch of a growing number of so-called “masculinity programs” aimed at instilling traditional gender roles in boys and young men through outdoor sports and classroom training. Last year, one such club in Beijing attracted attention – and some criticism – for having its students run shirtless in the dead of winter. “There is a crisis in boys’ education and I threw myself into practical actions to save them and help them find their lost masculinity,” the Boys’ Club founder told the South China Morning Post.

“‘Sissy men’ are under attack because they are perceived to be challenging the traditional notion of manliness,” said Fang Gang, an associate professor at Beijing Forestry University whose research focuses on gender studies and sex education.

Fang points out that, ironically, the current controversy is partly due to recent progress made by sexual minorities in China. Activists say a nascent but increasingly visible LGBTQ rights movement is slowly changing hearts and minds, encouraging greater social acceptance.

“Some parents extend their worries about perceived gender-neutral appearances by linking it to homosexuality,” he said. “Greater social acceptance of the gay community has only deepened fears among homophobic people, making them more anxious and afraid of non-mainstream masculinity.”

Others suspect a more direct link between the crackdown on “sissy men” and top officials’ worldviews, which for many were shaped during the Cultural Revolution.?

The strongman

President Xi’s attitude towards masculinity may trace back to his youth, which, from the late 1960s to mid-1970s, was spent in the Chinese countryside along with as many as 17 million other high school students and graduates. They were part of the “sent-down” generation relocated to the country’s far-flung corners to learn agricultural and political lessons from poverty-stricken peasants.

“In the summer, I was almost sleeping in a pile of fleas – all the bites and subsequent scratching turned my whole body swollen,” he wrote in 2002. “But after two years, I became used to it and could sleep through the night no matter how much I got bitten.”

The Chinese leader’s definition of manliness also has a political dimension. During a meeting with officials in southern China just months after taking power, Xi reportedly lamented the lack of strong convictions among Soviet communists when their party was on the verge of collapse. He was widely quoted by overseas Chinese-language media as saying that: “In the end nobody was a real man, nobody came out to resist.”

Xi’s government seems determined to resist the perceived feminization of Chinese men through regulations and propaganda.

In a sign of a tightened political environment, artist Ming was reluctant to acknowledge the sensitivity of his art, which includes an almost-naked portrayal of the iconic PLA soldier from the Cultural Revolution-era opera “Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.”

“Strength is needed – with muscles – for militaries, revolutions and the proletariat, which means manual labor,” said Ming. “But in traditional Chinese art and literature, male beauty is about being delicate, pale and pretty,” he added, pointing to a contradiction in the way men have been depicted through history.

“I paint from a Chinese perspective – and my work is on a continuum of Chinese aesthetics,” he said.

For now, Ming’s website remains blocked in China and the artist doesn’t foresee his work being exhibited in his home country anytime soon. The cultural tradition that inspired him appears increasingly incompatible with the muscular strength appreciated and projected by the Chinese leader at home and abroad.

Last year, China’s largely ceremonial parliament endorsed a constitutional amendment scrapping presidential term limits and paved the way for Xi, 66, to stay in power indefinitely. Nevertheless, Ming anticipates an eventual change of guard in leadership – and the impact it could have on cultural attitudes.

“The older generation finds it harder to accept new things … it applies to not just ‘sissy men’ but many other things,” he said. “I think we need time.”