Story highlights

Associated with the underworld, tattoos were once stigmatized in China

But in the past decade, they've become more socially accepted

Trend driven by a younger generation that isn't afraid of standing out

Tattoos have a long history in China. But for most of that history they were stigmatized, associated with prisoners, vagrants and the criminal underworld.

Thanks in part to the influence of celebrities and sports stars, tattoos have become much more socially accepted in the past decade.

It’s a trend driven by a younger generation that isn’t afraid of standing out but also by the sophisticated skills of China’s tattoo artists.

“Ten years ago we still associated tattoos with bad people or gangsters. People who wanted to get one were afraid of discrimination from society,” says Liao Lijia, 28 a tattoo artist at Creation Tattoo in Beijing.

“But tattoo culture is well accepted by Chinese people these days, especially in Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou.”

Scores of parlors are opening up in cities across China, and many are taking up the tattoo gun hoping to get in on the increasingly lucrative trade.

“Over the past three years, the number of customers has doubled each year,” says Yu Haiyang, Liao’s boss. His studio takes on average around $10,500 a month.

“My income is 10 times more than six years ago,” he adds.

Identity

Getting inked is one way for young people to forge their own identity and mark life experiences – bad or good.

“I think a tattoo is a sign of myself, like your name. It’s the most special part of your body, it makes you different. Shows your mind, your world,” says Wang Zi, 28, a fashion designer.

She has a tattoo of a hot air balloon on her shoulder blade, a design she drew herself to cherish a childhood dream of flying in one.

Du Wei, 28, works in IT in Beijing. She has a tattoo of a butterfly on her chest – representing the memory of a baby she lost.

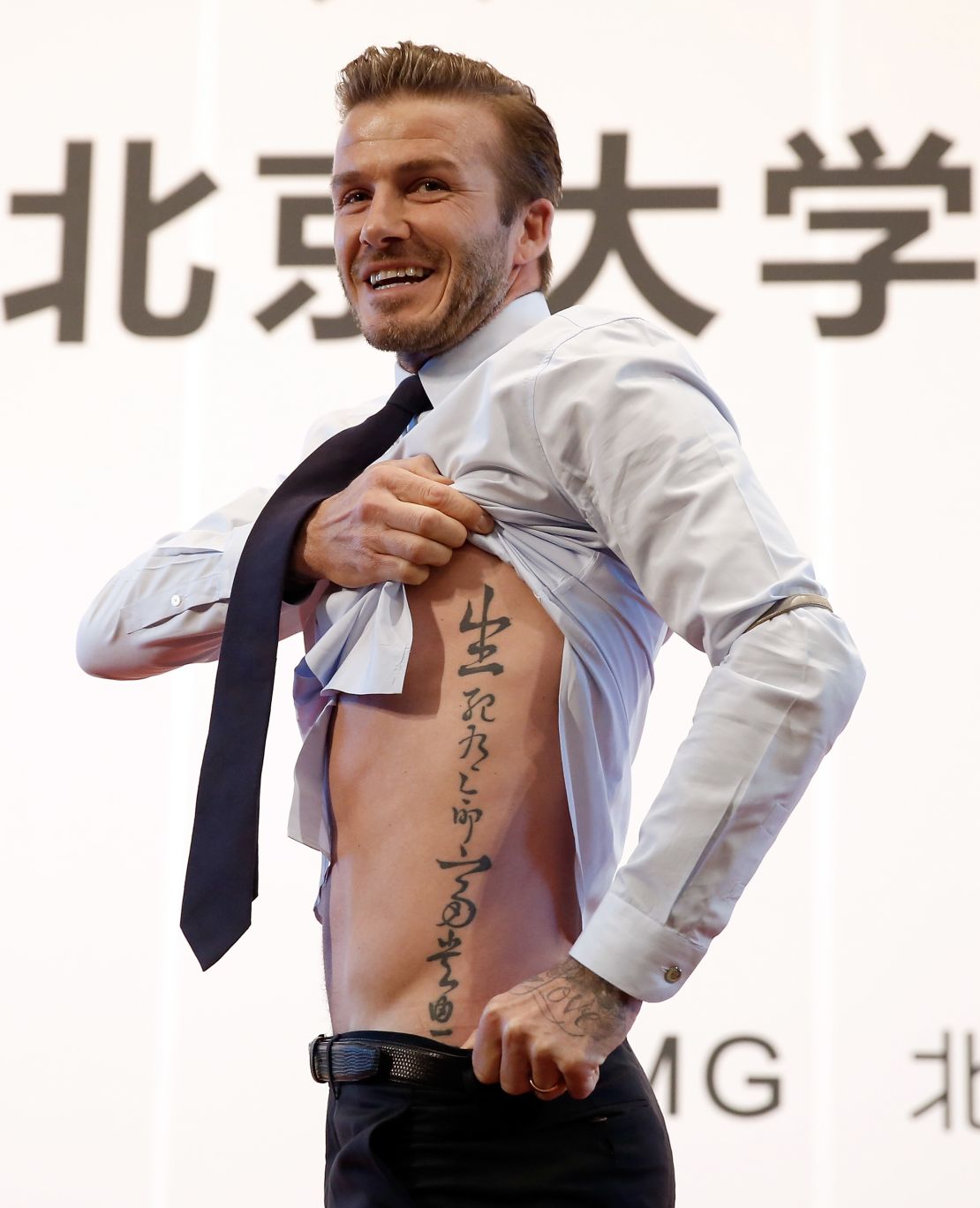

Just as Chinese characters are a popular choice in the West – David Beckham famously has a Chinese proverb tattooed on his torso – in China some people like tattoos of English words and phrases.

Popular words include “love,”and “forever.” Others choose song lyrics such as lines from the John Lennon’s song “Imagine,” or quotes from the Bible.

Tattoo artist Da Hua shows off a quote scrawled over the forearm of one client that reads, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” He also takes inspiration from Chinese legend, creating art that melds time and cultures.

Chinese flair

Asia has long had its own tattoo culture. Japan is famed for its bold and highly developed style.

Hong Kong is also a bastion – the port city catering to British sailors of old, giving rise to a mixture of traditional western tattoos – the rose, the anchor – with oriental motifs such as the dragon and the tiger.

China is starting to develop its own unique styles, drawing on both ancient and modern inspiration.

Qiao Zhengfei is a 20-year-old tattoo artist who opened up her own studio in her native Xiamen before moving her business to Beijing.

She specializes in “blackwork,” an intricate form based on a style of embroidery. The former art theory student likes the fact that tattoos are a living embodiment of her work.

“It’s an aesthetic choice,” she says. “I couldn’t see myself doing traditionally Chinese tattoos like dragons and fish. They don’t resonate with me.”

A trade or art?

In China, some parlors are cubicle affairs, a small square room with a curtain and heavily tattooed proprietors.

Others boast large studios with grungy aesthetics and art adorning the walls.

The Chinese tattoo artists I spoke to shied away from calling their work an art form, viewing it as a trade.

Eight years ago, Zhao Liang graduated from teaching college after majoring in art and planned to find a teaching or civil service job.

“But they both were not well paid jobs. Since I have to support my family I thought I should find a job that can earn a living.”

One day, he saw a poster advertizing tattoos for 50 yuan ($8) each and thought about giving it a go.

“Then I started doing (it). I just thought life is going to be better and better.”

Lu-Hai Liang is a freelance journalist based in Beijing. Researcher Danni Zhu contributed to this report