Editor’s Note: This feature is part of Vision Japan, a series about the visionaries who are changing Japan, and the places that inspire this innovation. See more here.

Story highlights

Cutting-edge Japanese architecture is drawing on nature for inspiration

Buildings are built around trees, in trees and as trees

Japan's culture of resilience is built into its architectural practice

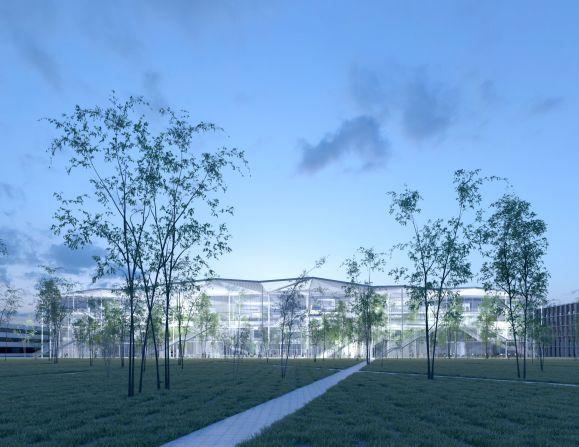

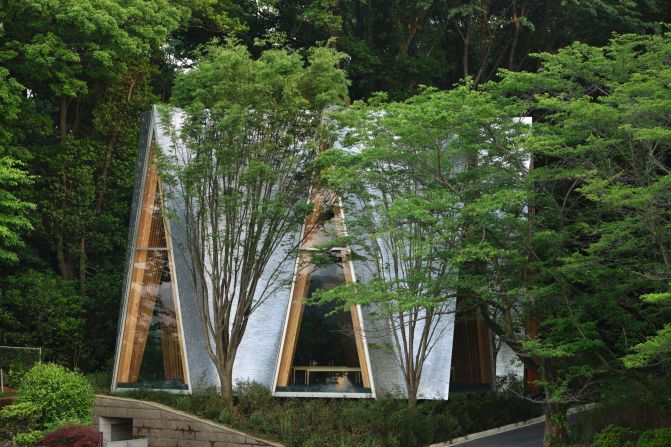

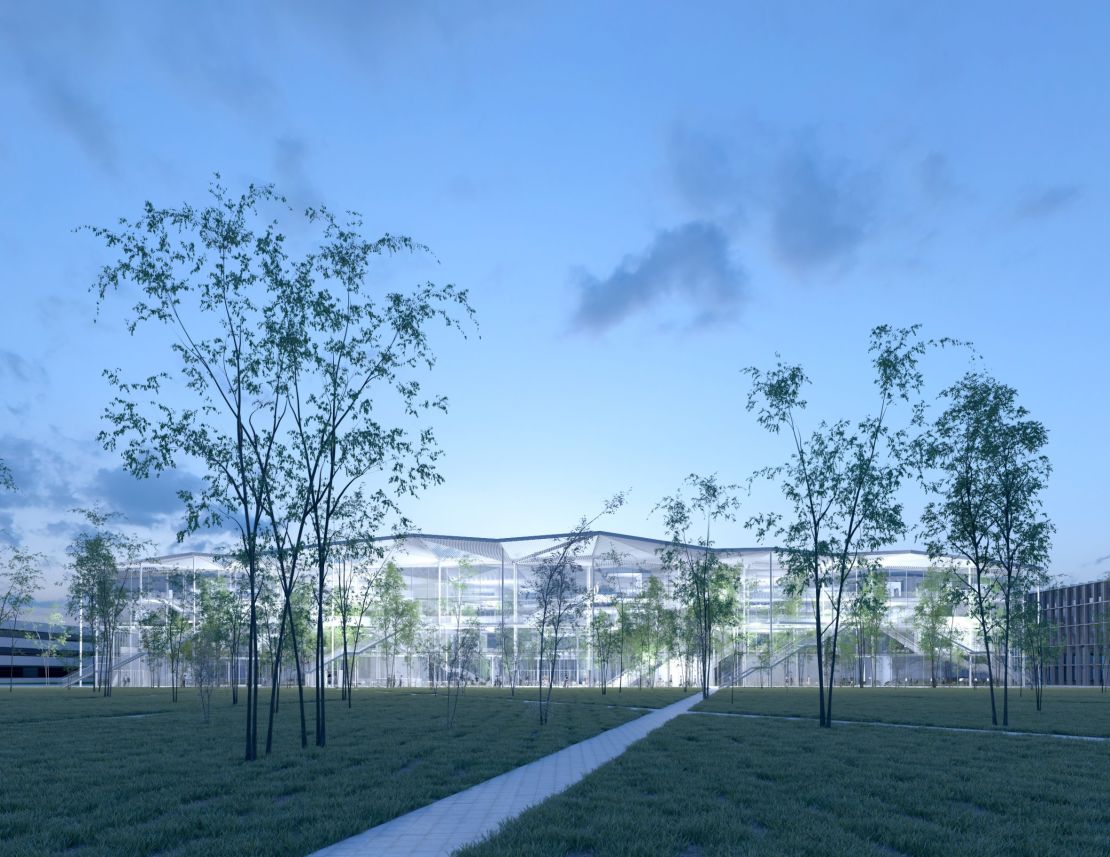

In Japan, the line between nature and the built environment is a blurred one and the country’s leading architects are using this concept to create innovative and cutting-edge designs.

Sou Fujimoto is at the forefront of Japan’s forward-thinking design and is known for integrating nature into his work. His designs include cloud-like structures like the futuristic Serpentine Pavilion, in London, and a glass, transparent house in Tokyo inspired by the life of a tree.

Another celebrated architect, Toyo Ito has twice won the prestigious Pritzker Prize, and it’s no coincidence that some of his most inventive works are designed to be experienced like forests.

His Mikimoto Ginza, Tod’s Omotesando and Sendai Mediatheque incorporate tree-like elements, and light falls into the buildings like it would a forest.

Nature in buildings

While the designs are forward-looking, they have their origins in a tradition deeply rooted in Japanese culture, where architectural practice has always been to work in harmony with the natural surroundings. Buildings are built around trees, in trees and as trees.

It’s difficult to know when this philosophy began. It has “always been there,” says Neil Jackson, an expert on Japanese architecture from the University of Liverpool in London.

However, one clue can be found in the Japanese writing system. Put together the pictogram (Kanji) for “house”, and the pictogram for “garden,” and you get “home.” The space inside and outside the building is continuous.

The source of this approach is, in many ways, a result of Japan’s mountainous landscape and exposure to extreme weather events, like earthquakes, which thrusts nature to forefront of daily life. As such, the country has limited spaces for living, with most of the population on the coast.

“People’s relationship to nature is very immediate. People are very crammed in,” Jackson explains.

In some cases, traditional rural buildings can be opened entirely to the surroundings. “Japanese buildings often don’t have doors. When the weather is very hot, especially in poorer communities in Japan, they would just open up the entire building. Nature flows through the living space,” Jackson says.

Finding nature in cities

In contemporary Japan, over 90% of the population lives in urban areas. But even in the country’s dense, futuristic concrete jungles the relationship to nature exists.

“Japanese urban living is quite tight and condensed,” says Jackson. “Yet within these very tight plots you get extraordinary open situations almost as if there’s no container, or containment, at all.”

Resilient architecture

The relationship between nature and buildings is also about survival. Buildings can be very lightweight, raised above the ground and flexible to twist and absorb the shock of an earthquake.

Ito’s acclaimed Sendai Mediatheque building, in Miyagi, survived the devastating quake of March 2011, in part because of the innovative use of tree-like flexible supporting tubes within the building.

Jackson comments: “There’s a huge ability in Japanese culture to survive disasters.”

Tadao Ando is a self-taught architect highly regarded for his contribution to modern Japanese architecture. He creates mostly concrete, sculptural buildings that focus on the flow of natural light.

Jackson explains: “His work, despite using concrete, reflects that same fizzling of nature and building. Nature is also caves and spaces within the land.”

Japan’s culture of resilience is built into its architectural practice, and its ideas about openness translate to even the most modern forms of urban living.

In Japanese thinking there is no built or natural environment – just nature.