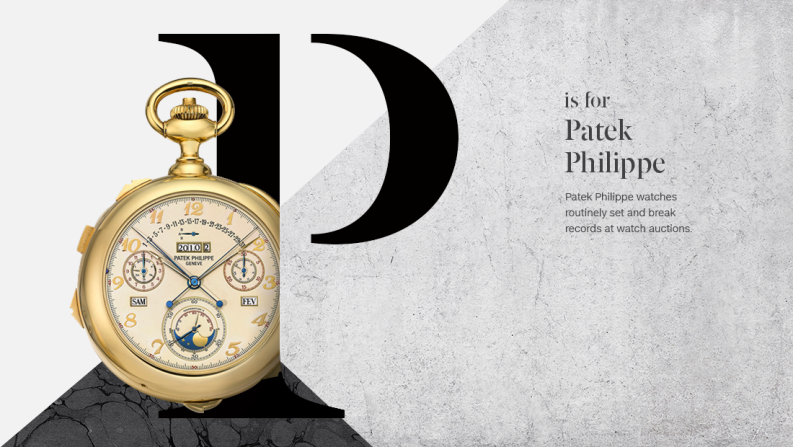

The world record holder for the most expensive wristwatch ever sold at auction isn’t a lavishly appointed timepiece encrusted in diamonds or encased in 24-karat gold. Instead, the title belongs to a relatively understated, stainless steel watch made by Patek Philippe in 1943. In November 2016, the watch went for a staggering $11 million to an unnamed private collector, courtesy of the Geneva branch of the Phillips auction house.

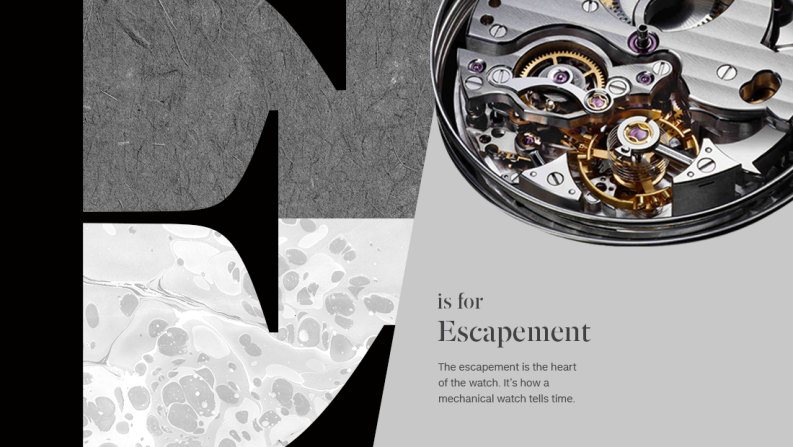

But don’t let its simple appearance fool you. Open the watch case, and you will find nearly 200 individual hand-made components working in harmony in pristine condition in a space a mere fraction of the size of the average smart phone. The inner workings are, to riff on watchmaking parlance, very complicated, a trait that has become a company signature.

“Patek Philippe is never easy,” says Sandrine Stern, the brand’s head of creative and wife of Patek Philippe president Thierry Stern. “Never.”

Fostering an understanding of the detailed craftsmanship that goes into every Patek watch is one of the reasons the company has organized “The Art of Watches,” an interactive, 10-room, 13,200-square-foot retrospective at Cipriani 42nd Street in midtown Manhattan open now through July 23, that aims to, as Stern puts it, “show what is Patek Philippe, in terms of movement and innovation.”

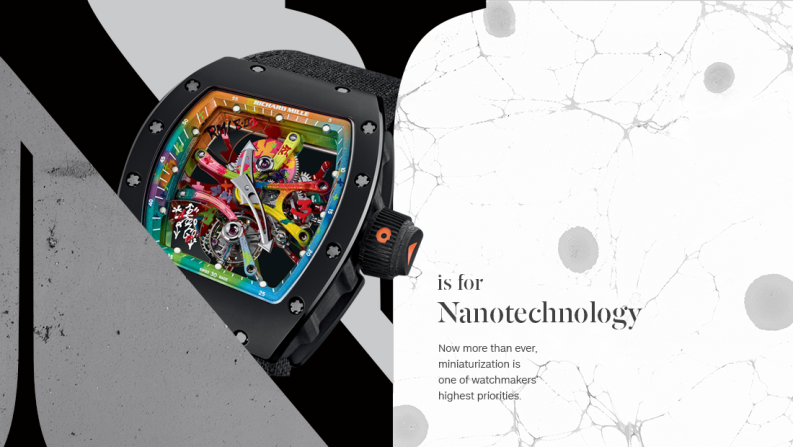

At Cipriani, visitors can learn about a watch’s movement (the technical term for its inner mechanics) and its appropriately named complications – the word for any function a watch performs other than telling time.

Patek Philippe has contributed to advancements of both. The company helped pioneer the chronograph movement, annual calendar and perpetual calendar that accounts for leap years. Guests to the exhibition can observe the craftsmanship that goes into each high-end timepiece, via a handful of artisans working on-site and a virtual reality tour that takes viewers inside a Patek Philippe watch.

Read: Japan’s 700-year-old ‘oke’ craft gets a modern makeover

Historical artifacts from the Stern family’s private collection, some of which date back to the 16th century, can be viewed side by side, as can a bevy of one-of-one Patek Philippe items meant to show off the company’s technical prowess.

“You can see the knowledge of Patek Philippe,” Stern says of the show. “We cannot focus only on one piece, because the knowledge is so huge today.”

‘The absolute premier brand’

The record setting, $11-million wristwatch – known by its reference number, 1518 – is not on display, but pieces once owned by John F. Kennedy Jr., Duke Ellington and Joe DiMaggio have been assembled for the event. They’re among the serious collectors and seriously wealthy clients who have found Patek timepieces irresistible since the company was founded in 1839, often ahead of its competitors with equal or greater brand recognition.

“Within the world of collectible watches, Patek Philippe has always been the most desirable,” says Benjamin Clymer, a high-end watch expert and founder of Hodinkee, a website devoted to the finest in watchmaking. “It’s always been the absolute premier brand.”

By way of comparison, Paul Boutros, head of watches at the Americas division of Phillips auction house, notes that the most expensive Rolex ever sold at auction – the Bao Dai, a yellow gold, automatic style – bought for $5 million at Phillips in May. That number was millions shy of the previous wristwatch record-holder, another stainless steel Patek watch sold at Phillips for $7.3 million in 2015.

(Patek also holds the clear record beyond wristwatches, with the $24-million sale of banker Henry Graves Jr.’s pocket watch at Sotheby’s in 2015.)

“Rolex is approaching, but still a bit away,” Boutros says.

Read: Where to see the world’s most beautiful jewels

The relatively plain stainless steel casing of the $11-million 1518 actually ended up being an asset: of the 386 versions of that watch produced, 382 of them were made in either yellow or rose gold, Boutros says, and only four in steel.

“To find another 1518 in steel, you’ll have to wait another generation until one comes to market,” he explains. Even today, when the industry produces roughly 20 million timepieces a year, Patek makes just 50,000. It is estimated that the company has produced less than 1 million total since it was founded.”

He adds: “People really covet what they can’t have and are wiling to pay a significant premium.”

Final flourishes

Patek acolytes don’t need the New York exhibition to educate them about the company’s reputation for craftsmanship, though that, too, is a key selling point.

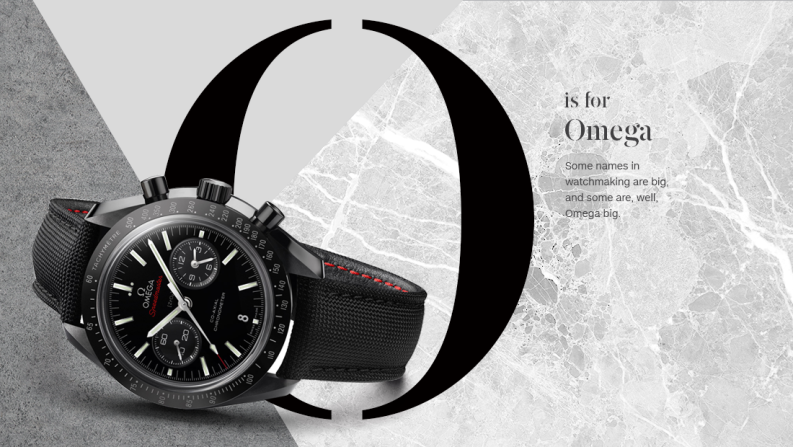

“Technically speaking, Patek Philippe watches are all hand-made and finished, whereas many pieces, even such as (those produced by) Rolex or Omega, typically are finished by machine,” Clymer says. (Finishing implies that even a hidden movement is decorated for aesthetic value.)

“Rolexes and Omegas, things like that, are seldom finished, meaning they create a movement that works and then they close the case back, and that’s it.”

Read: The greatest timepieces to grace the silver screen

If flourishes like hidden finishing seem extravagant (in the way that the company erecting a temporary museum in its own honor in the middle of Manhattan does,) Patek’s long-held commitment to grandiosity, regardless of price, is built into the brand’s ethos.

“They never created a sub-line,” says Boutros. “You can get a Patek Philippe for $10,000 today minimum, but you can’t buy a Patek Philippe for $2,000. These are the most complex type of timepieces that only very skilled and very seasoned watchmakers can do well.”

All you need to know about serious watches, from A-Z

Clymer confirms that headline-grabbing auction sales likely contribute to the brand’s appeal in the more traditional selling market, but notes that changing consumer behavior does pose a challenge – in spite of those big numbers, or possibly, because of them.

“In many ways, the people that we admire the most now are casual,” Clymer says. “They dress very nicely, but also very casually. With that, a crocodile strap and a gold watch don’t necessarily make the most sense.”

Read: Watchmakers dig up past to secure the future

While the brand may not be heading toward an athleisure collection, Clymer expects the company will address that shift with more steel and sportier versions to appeal to a younger consumer, with the same trademark complications upon which Patek built its name – even if the uber-moneyed, traditional Patek customer may not respond to it.

“They’ll rumble, they’ll complain, they’ll make little snarky comments to their friends,” he predicts. “But ultimately, if you’re a collector, you’ll buy it anyway. No matter what, even if you don’t love the decision, you’re going to buy it because it is Patek Philippe.”

“The Art of Watches” is on at Cipriani 42nd Street in New York until July 23, 2017.