Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of special features ahead of the inaugural RIBA International Prize for the world’s best building, announced on November 24. Jonathan Glancey is a British architecture critic and author.

Story highlights

The Royal Institute of British Architects will be awarding the first RIBA International Prize in November 2016

The grand jury will draw upon lessons from centuries of great architecture as it chooses its building of the year

Celebrated 20th century German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said architecture began when two bricks were put together well. This might sound simplistic, yet Mies was right – architecture is the self-conscious act of building, not just with common sense but also with artistry.

There will always be debate over the origins of the art, but the first works we recognize as architecture were built from tiers of sun-baked mud bricks in what is today’s southern Iraq. Although the buildings they formed have been rebuilt over the centuries, they were so well conceived that some – like the Ziggurat of Urnammu at Ur – have endured for millennia.

However, there is architecture and there is great architecture, and what constitutes the latter has exercised the minds of generations of critics, theorists, historians and architects themselves.

This year, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) hopes to advance this thinking with its inaugural RIBA International Prize. This “formidably rigorous” award will be presented in November to the architects of the building considered to be”the most significant and inspirational of the year.”

RIBA International Prize: 30 stunning feats of design battle to be the world's best building

The grand jury that makes the final decision on which building this will be is chaired by Richard Rogers, an architect famous for two 20th century ‘greats’, the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Lloyd’s Building in the City of London. He is supported by four other architectural luminaries – Kunlé Adeyemi, Philip Gumuchdjian, Marilyn Jordan Taylor and Billie Tsien.

Building greatness

Rogers and his fellow judges have strict criteria to guide them. The chosen building has to demonstrate “visionary, innovative thinking and excellence of execution, while making a generous contribution to society and to its physical context - be it the public realm, the natural environment or both,” according to RIBA.

But these architects know full well that truly great buildings – the ones that catch our eyes, steal our hearts and send shivers up our spines – are rare, and that while good and even special buildings may emerge in any one year, none might be truly great.

As Frank Gehry, architect of the much-feted Guggenheim Museum Bilbao says, “Architecture should speak of its time and place but yearn for timelessness.”

We can date buildings of all eras with remarkable precision today, yet there are those – from the Pyramids at Giza and the Parthenon in Athens through to Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion, Le Corbusier’s pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamp and, yes, Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim – that will thrill people for centuries to come.

Some of these are imposing constructions, others modest, and not all of them have been costly to build.

“Making a great building is not about having lots of money, though you could make an argument that money helps,” says Richard Rogers. “Some of the best British architects have used the humble barn as the basis for intelligent, sophisticated and new buildings.”

Indeed, Rogers could have mentioned Mies, who traveled to London to receive RIBA’s Royal Gold Medal for Architecture in 1959. When asked by his hosts if he would like to visit some British buildings, the great architect chose to visit just one – the cathedral-like early 14th century timber and stone tithe barn at Bradford-on-Avon in rural Wiltshire.

Whether cheap or costly, humble or aloof, the timeless quality of great buildings has much to do with proportions, ratios and mathematics as it does with intangible poetic qualities.

As the influential 20th century American architect Louis Kahn put it, “a great building must begin with the unmeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed and in the end must be unmeasurable.”

Agents of change

As timeless as they may be, what makes a great a building is changing and has been since the Pompidou Centre in Paris was completed in 1977 to designs by Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano and structural engineer Peter Rice.

To many at the time, this iconoclastic public art gallery was an affront: wearing its insides on its outside, it was portrayed as a parody of an oil refinery. Even Rogers likes to tell the story of an elderly Parisian lady who hit him with her umbrella when he admitted that he was one of the building’s architects.

For judge Philip Gumuchdjian, the Pompidou was striking for quite different reasons.

“The importance of the experience for me was to suddenly turn a street corner in Paris and to see a completely new concept of building, of public space, of institution,” he says. “For the very first time in my life I realized that architects, architecture, a building, could change the way society functions, changes and moves forward.”

So a great building can be an agent of change, not purely in terms of structure or aesthetics, but socially, too.

Future forms

In the second decade of the 21st century, the latest developments in computer design and robotic construction mean that the ultimate form of future buildings may morph as they emerge from the ground. This is a complete change to traditional building design, yet it may give us great buildings imbued with a new kind of beauty.

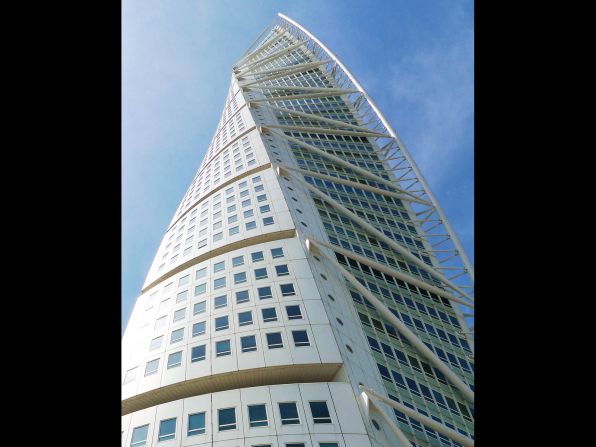

Tall and twisted towers

“A great building is one?that cannot have been imagined before it was created,” Gumuchdjian notes. “It’s a building that inserts inspiration into the backdrop of our every day life, a building that pulls us together as a society, a building that questions the way we live and empowers us to expand our understanding of the possible.”

Ultimately the judges of the first RIBA International Prize will be looking for a building that reflects the guiding philosophy of the studio Billie Tsien runs with her partner Tod Williams in New York.

Tsien says that she and Williams try to “make buildings that will last and…leave good marks upon the earth,” and names time and love as the two essential ingredients that make a great building.

“Nothing is immediately great, but we see architecture as an act of profound optimism. Its foundation lies in believing that it is possible to make places on the earth that can give a sense of grace to life – and believing that this matters. It is what we have to give and it is what we leave behind,” she and Tod write.

Transcendence, endurance and love. Here are three qualities the RIBA might want to add to Roman architect Vitruvius’s famous 1st century list of essential qualities of architecture – “commodity, firmness and delight” – to evoke the spirit their judges hope to find in the finest building of 2016.

It might just turn out to be truly great architecture, too.