Editor’s Note: Noah Charney is a professor who teaches the history of art crime. He is the bestselling author of The Thefts of the Mona Lisa: On Stealing the World’s Most Famous Painting, all profits from which support art crime research.

Story highlights

December 14 marks the 100th anniversary of when Mona Lisa was returned after being stolen

It was snatched by an Italian handyman who worked inside the Louvre

He had mistakenly thought that Napoleon had looted it and wanted to repatriate it

Confusion remains where Mona Lisa was kept during WWII

When the likes of George Clooney, Matt Damon, and Bill Murray come storming across film screens this winter, in the drama The Monuments Men, viewers will be immersed in the world of Nazi art theft.

The Monuments Men were a group of some three-hundred Allied officers charged with locating, protecting, and recovering art and monuments that were endangered by the fighting in World War II. They would eventually learn of Hitler’s elaborate and highly-organized plan to strip Europe of its art.

Indeed, Hitler had established a military unit solely dedicated to art and archive theft and made detailed plans to restructure the entirety of his boyhood town of Linz, Austria, into a city-wide “super museum,” containing every important artwork in the world. We have the so-called Monuments Men to thank for the salvation of tens of thousands of masterpieces, among the estimated five million cultural objects stolen during the war.

But while the film will focus on two great trophies, Jan van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, and Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna, there will be something of an elephant in the screening room. For a fascinating question remains, and one with a complicated answer: did the Nazis steal the Mona Lisa? The answer is that they thought they did.

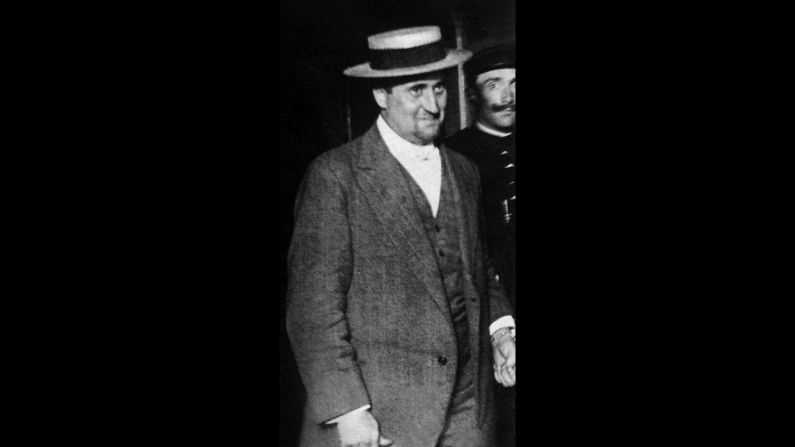

Mona Lisa’s vanishing act

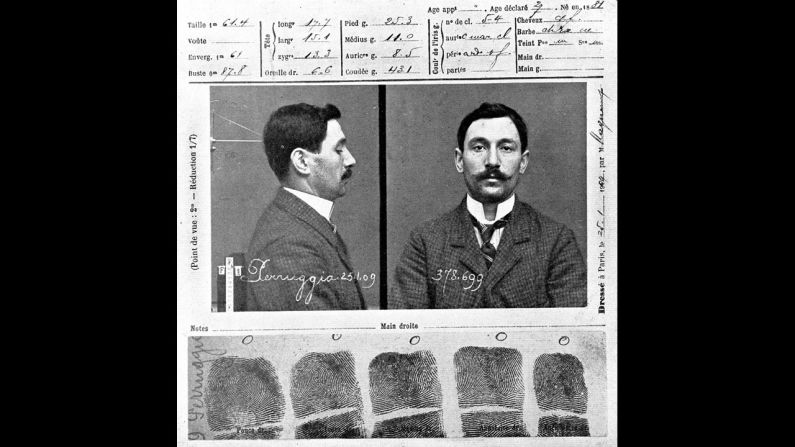

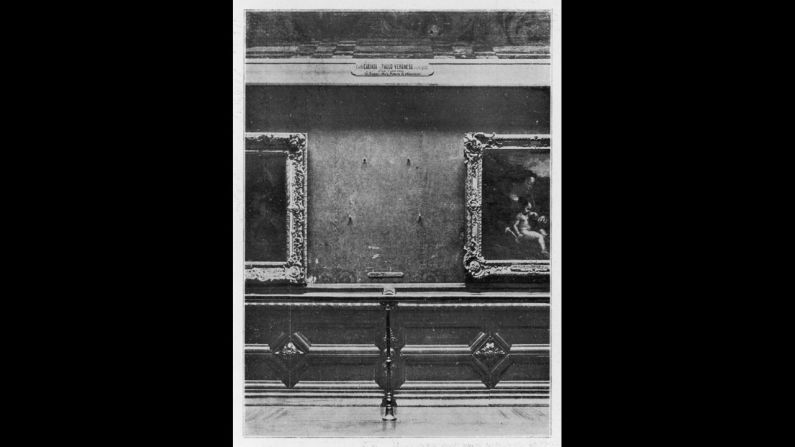

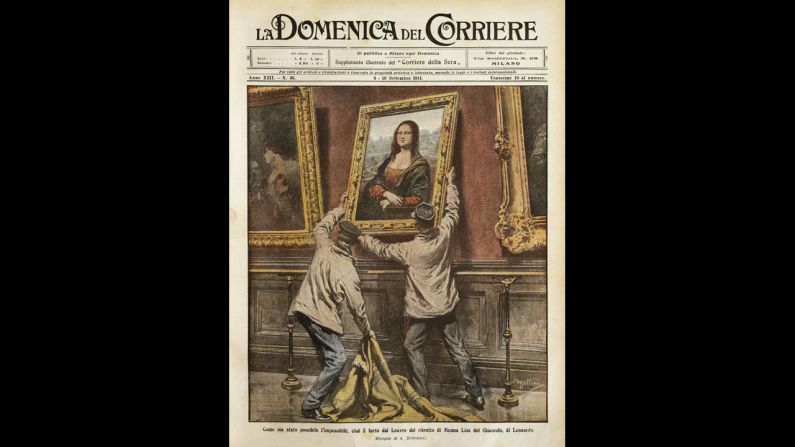

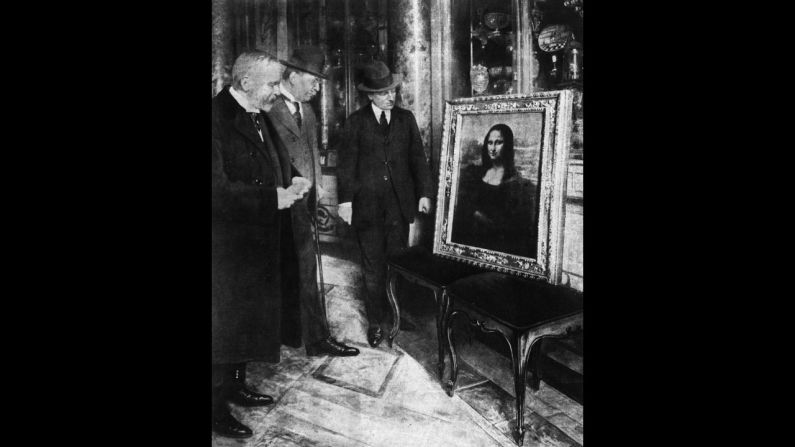

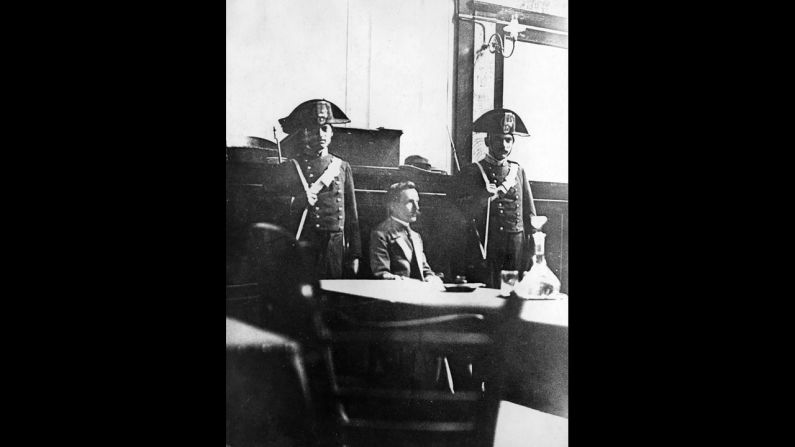

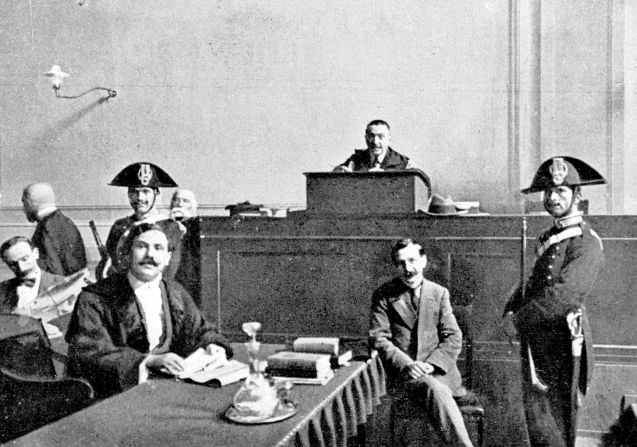

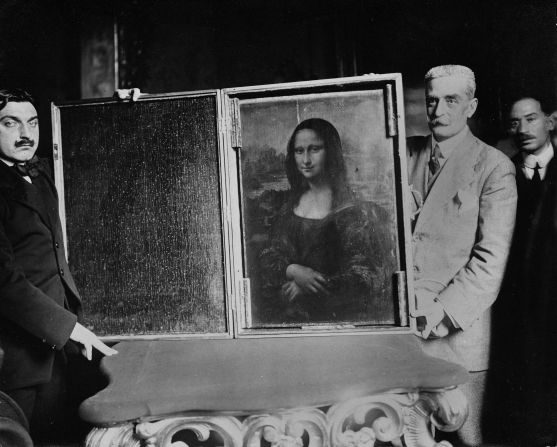

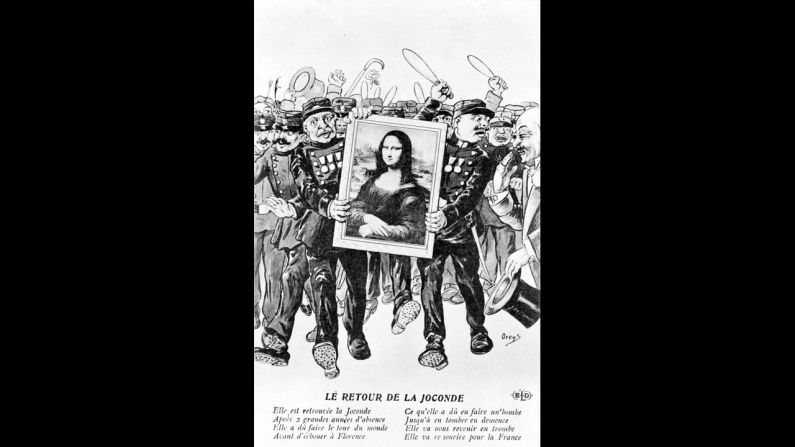

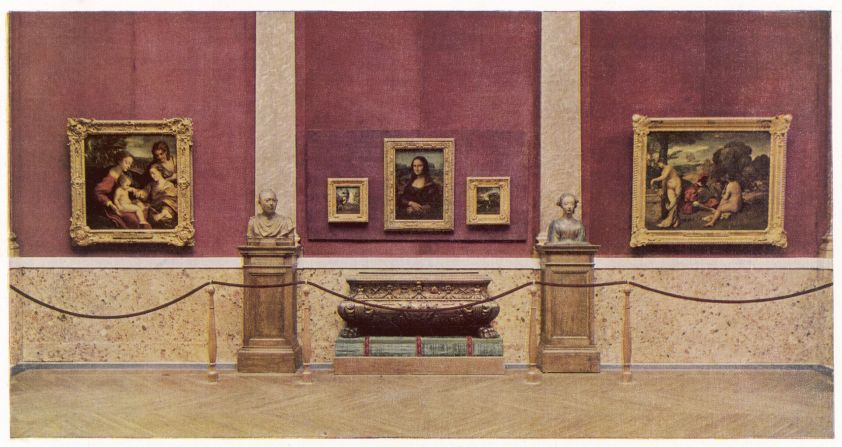

The most famous act of theft associated with the Mona Lisa took place about a century ago. December 14, 2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the return of the world’s most famous painting to public display, after it was stolen in 1911 from the world’s most famous museum. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was swiped from the under-secured Louvre Museum by an amateur Italian painter and handyman named Vincenzo Peruggia.

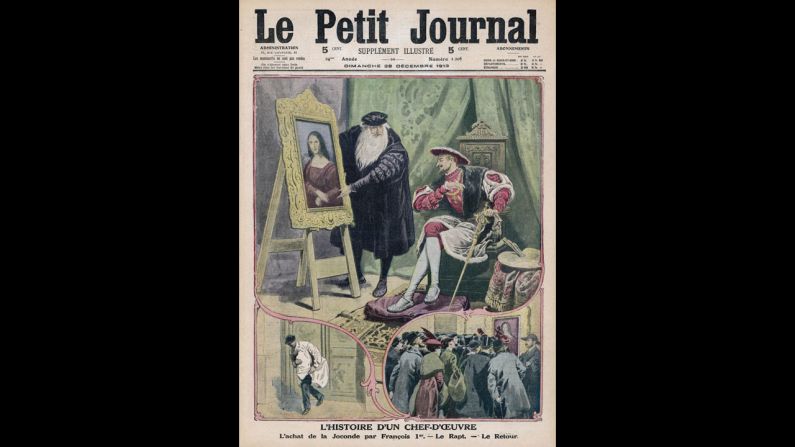

Peruggia was under the mistaken impression that the painting had been looted by Napoleon, during his Italian campaign. This was a pretty good guess, for through his art theft unit (the first military unit in history dedicated to art theft), Napoleon had made off with tens of thousands of artworks during his Italian campaign. Leonardo’s painting was not among them, however, as it had left Italy with the elderly Leonardo, when he spent his twilight years under the protection of the French king, Francois I, who legally purchased several of his paintings after his death, the Mona Lisa among them.

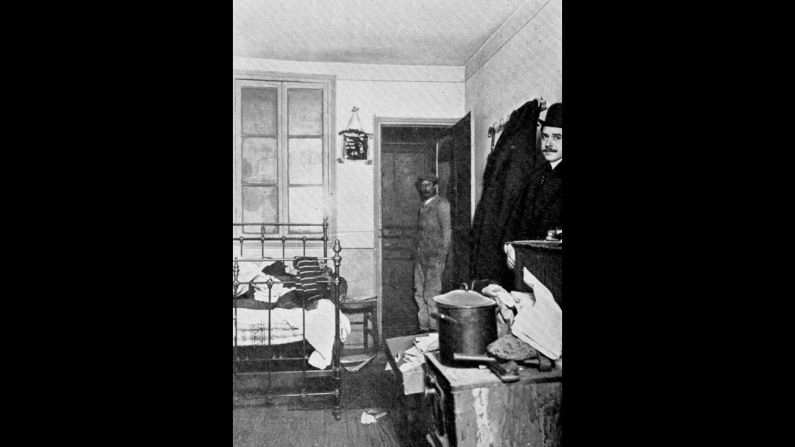

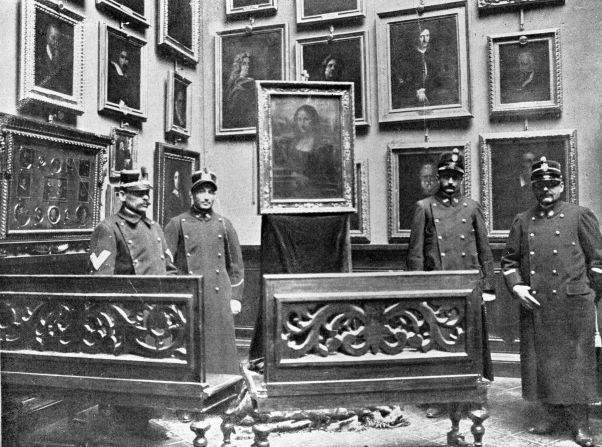

But Peruggia had missed the lecture on this historical detail. He saw an opportunity to repatriate the painting when the firm for which he worked as a carpenter and glazier was hired to build protective cases to cover some of the Louvre’s most famous works, ostensibly to protect them from attack, after an anarchist had slashed an Ingres painting in protest.

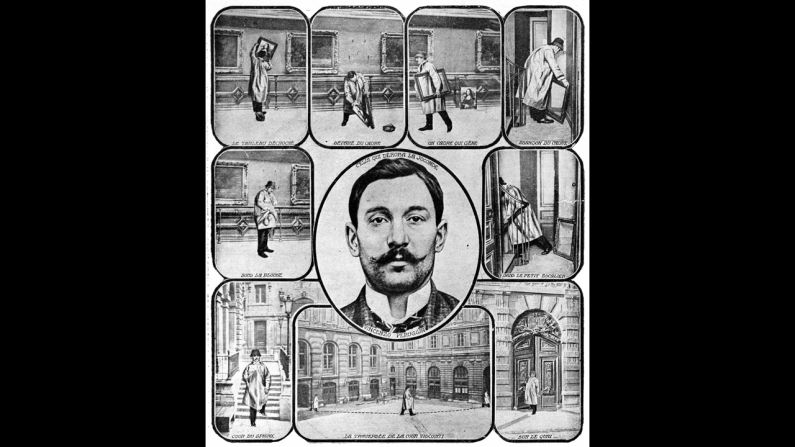

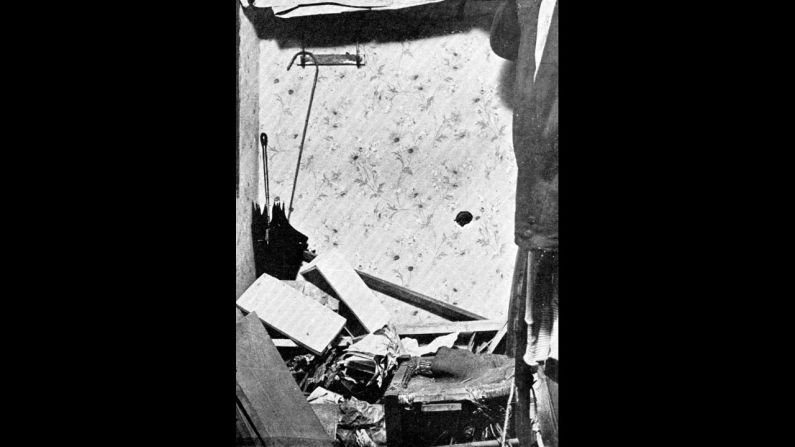

Peruggia found himself with a Louvre worker’s uniform, and direct contact with the Mona Lisa. On the night before August 2 1911, he hid inside a closet in the Louvre, waiting for the footfalls of the night guards to fade into the distance. In the early morning hours, he slipped out of the closet, removed the Mona Lisa from its wall in the Salon Carre of the Louvre, and retreated to a service staircase. There he took the painting out of its frame, wrapped it in a white sheet, and headed down the stairs.

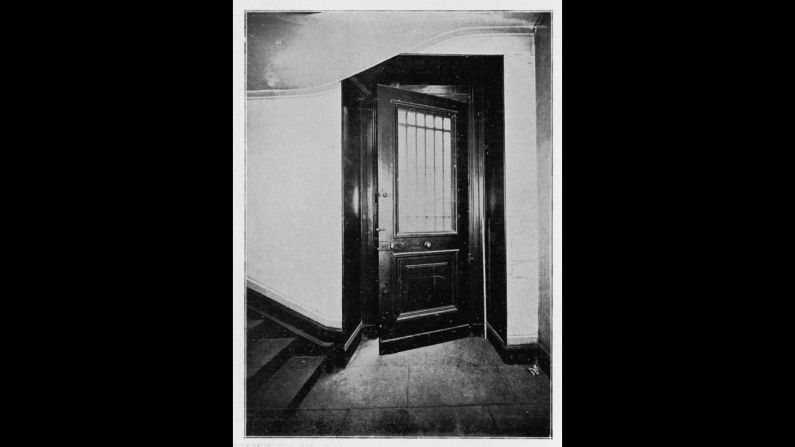

There was surely a moment of great panic, when Peruggia twisted the doorknob at the foot of the stairs, and found it locked from the inside. He was prepared for an eventuality such as this, and had tools with him. He unscrewed the doorknob and slipped it into his pocket, thinking this might unlock the door, but it didn’t.

He was trapped inside the Louvre, with the world’s most famous painting tucked under his arm…and then he heard the sound of footsteps approaching. Up the stairs came a plumber, making his morning rounds. To the plumber, Peruggia looked like a Louvre worker who had accidentally been locked in overnight—not an unheard-of occurrence. He opened the door and let Peruggia out, thinking nothing of the Mona Lisa-shaped package that Peruggia carried with him.

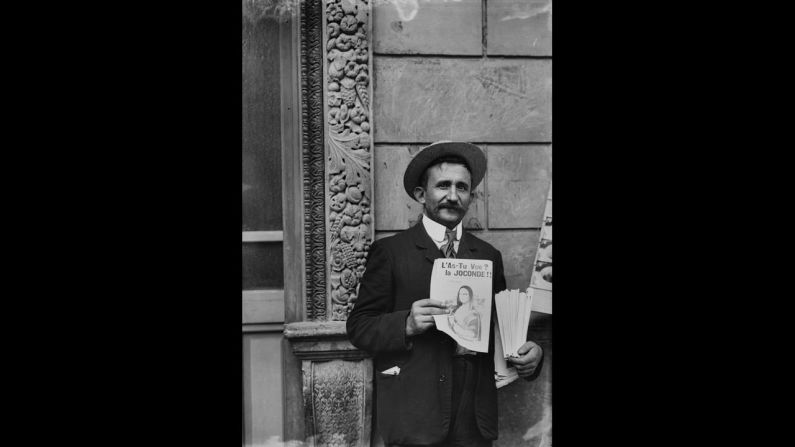

It would be two years before the Mona Lisa was seen again. The investigation was a fiasco that resulted in the dismissal of the head of the Louvre and the head of the Paris police. International media mocked the lack of security at the Louvre – in fact, this was the first theft to spark the interest of the world media, kicking off a love affair with the elite world of high-priced art, and its theft.

Priceless loot

The most cinematic and resounding success for the Monuments Men was the salvation of the 12,000 masterpieces destined for Hitler’s planned Linz museum, which were stored in an ancient salt mine at Altaussee, in Austria, which had been converted by the Nazis into a secret stolen art warehouse.

It was supervised by a ferocious SS officer, August Eigruber, who was determined to destroy all of the art if he could not defend it against the Allies. This is where the most famous pieces were kept, including gems by Vermeer, Raphael, Rembrandt, and a who’s-who of Old Master artists. But there is some confusion as to whether the Mona Lisa was there, as well.

There are two primary source documents that attest to the Mona Lisa’s presence in the Altaussee salt mine. The report of a secret mission called Operation Ebensburg, in which four Austrian double-agents were parachuted into the alps to delay the destruction of the Altaussee mine until the Allied Third Army could arrive, stated that the double agents “saved such priceless objects as the Louvre’s Mona Lisa.”

Another document from 12 December 1945 notes that “the Mona Lisa from Paris [is included in] 80 wagons of art and cultural objects from across Europe” that were found in the mine. And yet there is no record beyond these two documents of the world’s most famous painting being part of the world’s most famous hoard of looted art. Surely that would have been noteworthy, a rescued prize as famous as Adoration of the Mystic Lamb.

Shrouded in mystery

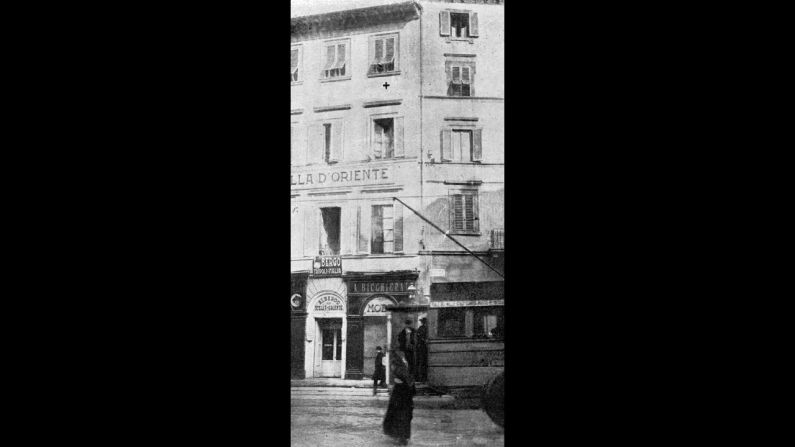

The Louvre remained reticent about whether it had lost the Mona Lisa at all. The only documents about the painting during World War II attest to its having been crated up on August 27, 1939, and sent with other French national treasures to a series of five chateaux, for safe-keeping—theoretically just ahead of the advance of the Nazis south through France, though the invaders quickly overtook the entire country.

Beauty from the crypt: Mystery of Europe's jeweled skeletons

The next document that refers to the painting is not until 16 June 1945, when the painting was listed as having been returned safely to the Louvre. Its whereabouts during the war are unrecorded. But are they unknown?

The latest word from the Louvre is that an identical copy of the Mona Lisa, also from the 16th century and difficult for any non-specialist to distinguish from the original, was one of a few thousand works that were gathered at the Musee Nationaux de la Recuperation, for whom owners could not be found. This copy was marked MNR 265. After five years had passed with no one able to prove ownership, it went to the Louvre. From 1950 onward, it hung on the wall outside the office of the director of the museum.

Based on the available evidence, and a little detective work, a plausible (though unconfirmed) conclusion may be reached as to what happened to the Mona Lisa during the war. A painting was crated up in 1939 and sent to various castles, just ahead of Nazi hands—but it was this 16th century copy, not the original. Knowing that the Mona Lisa would be such an obvious target for Nazi art hunters, the Louvre may have kept the original hidden in Paris, while the copy led the Nazis on a wild goose chase.

This would explain why the “Mona Lisa” did return from Altaussee, but why it may also be that the “Mona Lisa” never left Paris. It was the copy that was stolen, hidden at Altaussee, and recovered. Some who saw it assumed it was the original, while others, specifically the art-savvy Monuments Men who catalogued the art saved from the salt mine, recognized that it was only a copy.

To see Dr Charney giving a TEDx talk about the 1911 Mona Lisa theft, click here.