Editor’s Note: Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is a senior research fellow in fashion theory and practice at London College of Fashion, and the founder of the fashion journal Vestoj. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

Fashion has been long viewed with suspicion by culture hacks. Traditionally seen as a woman’s art, it has been associated with surfaces, vanity and excess. Venerable museums and institutions opening their doors to the medium is a relatively new occurrence, but it has proved a profitable one.

When the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, put on “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” (2015), it became the most popular exhibition in the museum’s history; likewise, the fashion exhibitions at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York, have more than once rated among the museum’s most visited.

However, as the museum prepares this year’s show and gala, due to open in May and titled “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” the focus yet again appears to be on mere beauty, depoliticized and, in this case, “opposed to any kind of theology or sociology,” as Bolton recently told the New York Times.

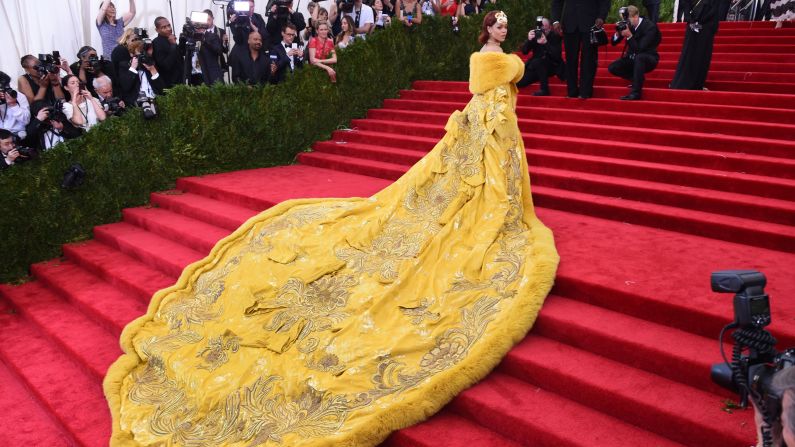

It’s no surprise that the Met audience loves fashion, especially not to visitors who patiently waited in line outside the museum to explore the shows “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” (2011) or “China: Through the Looking Glass” (2015). Almost 816,000 people saw ancient Chinese treasures juxtaposed with modern Western couture, making “China: Through the Looking Glass” the fifth most popular show in the history of the museum. At the time, Andrew Bolton, the curator of the Costume Institute, told the Guardian that the show was about the “collective fantasy of China.” Fantasy is a term often associated with fashion, used as much as a compliment as an insult hurled at its practitioners.

At the Costume Institute, fantasy is indeed the operative term. It’s used to justify avoiding a politically correct line of thought, in favor of a firm focus on the creative process.

The surface of fashion

Blockbuster fashion shows at the Met tend to focus on fashion as something apart from everyday life, exquisitely made and available only to the few. Shows like “China: Through the Looking Glass” or “Manus x Machina” (2016) present fashion that has been made using the most sophisticated techniques and intricate skills, whether the creation of man or machine. The garments on display dazzle and shine. Their purpose is to impress, by way of excess and surface decoration. Fashion, these exhibitions seem to say, is no place to get serious. Never mind sociology – stick to the fantasy. As such, the appeal of the medium resides in the superiority of its ornamental value, and in its emphasis on the facade. But how can you separate creativity from the cultural and political moment that gave rise to it, especially, as is the case this year, when the topic is religion?

It’s no surprise the Met are keen to revisit Catholicism, considering that their 1983 exhibition “The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art” is the third most visited in the museum’s history.

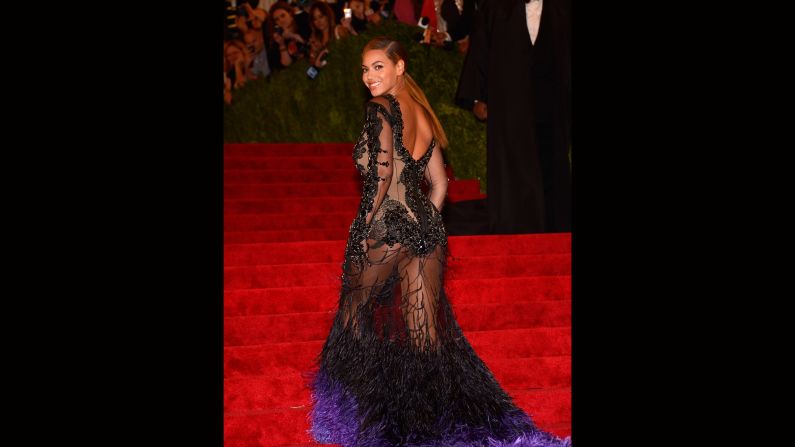

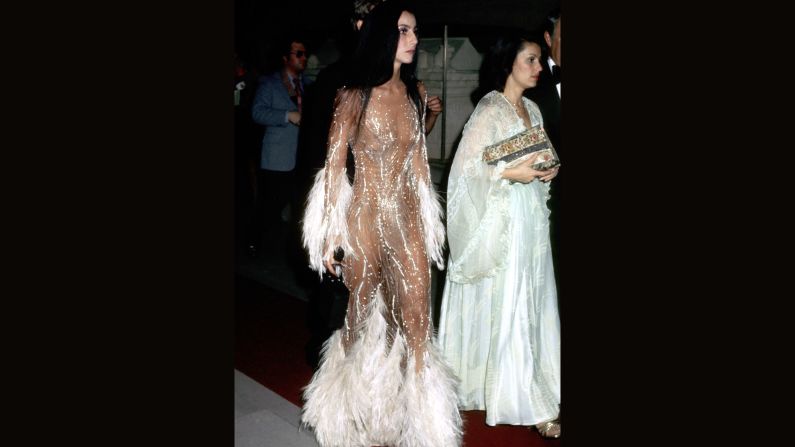

Christianity, as interpreted by the Costume Institute, means mixing the sacred and profane. There will be ecclesiastical garments on loan from the Vatican jostling for attention against high fashion by the usual suspects: Dolce & Gabbana, Versace, Chanel, Balenciaga and Valentino among them. No doubt, the Costume Institute Benefit will be, as usual, an equally predictable affair, as the bold and the beautiful compete for attention by feigning controversy, while remaining well within the boundaries of the game – cue Madonna in her 2017 camo Moschino gown, worn, according to the singer, to bring attention to “peace on earth,” and Beyoncé’s various barely-there gowns or Lady Gaga’s look-no-pants outfit from 2016. This is what we have come to expect from the blockbuster shows at the Met too: simulated provocation with just enough teeth to grab the necessary headlines but never enough to rock the boat.

Going deeper

It’s important to remember that the museum both confirms and produces cultural capital; through what powerful cultural institutions, like the Met, deign worthy of their attention, hierarchies of value are invariably reproduced and reinforced. The Met allows fashion into its sacred space, only when it’s synonymous with glamour and spectacle, and stripped of its power as a political force. In shying away from a more controversial take on its subjects, the Met appears stuck in a rather archaic view of culture – one that in light of today’s growing political and social awareness seems more and more irrelevant. The glitz and glamour associated with the Met gala reinforces the view that fashion is theatre, only truly creative when separated from the quotidian, religion, politics and economics.

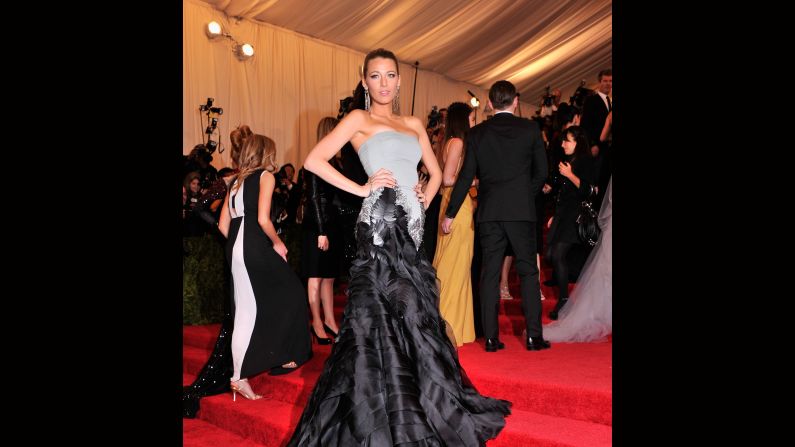

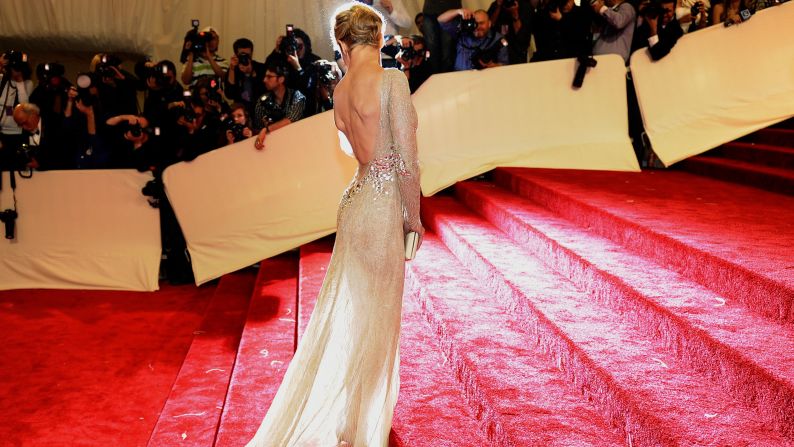

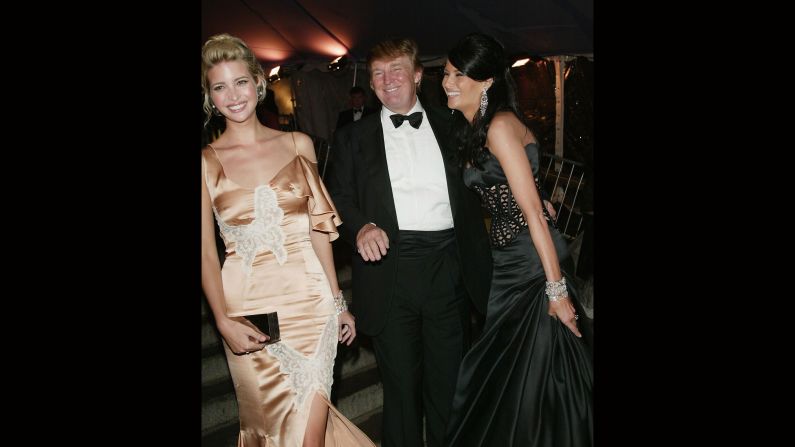

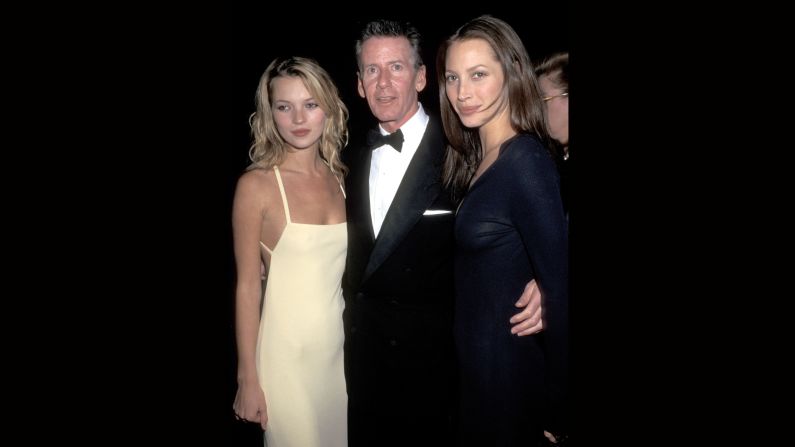

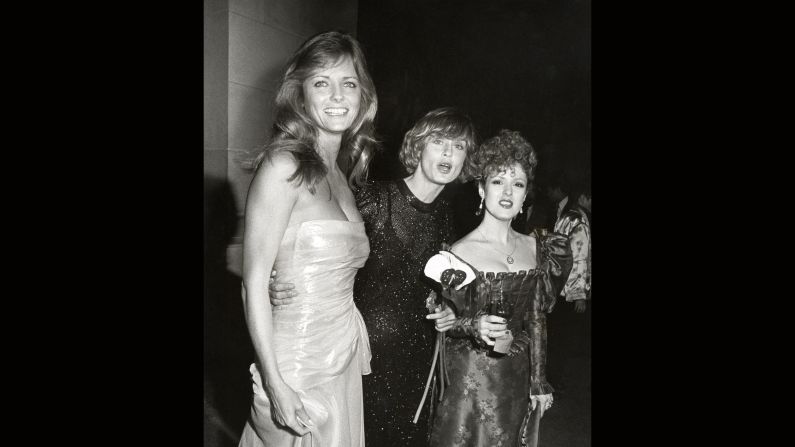

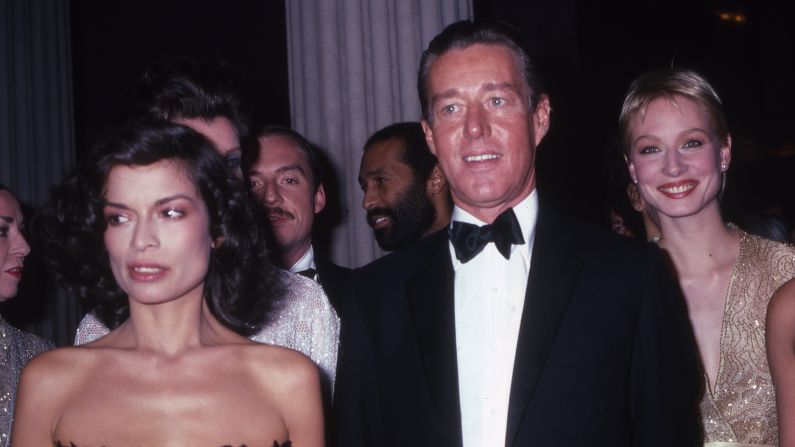

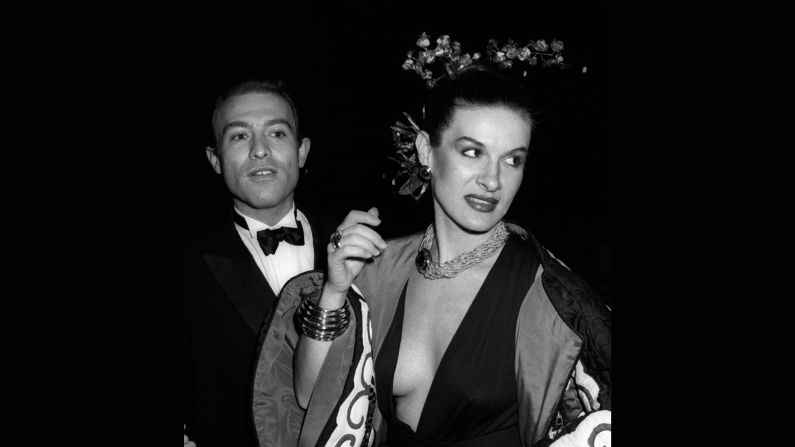

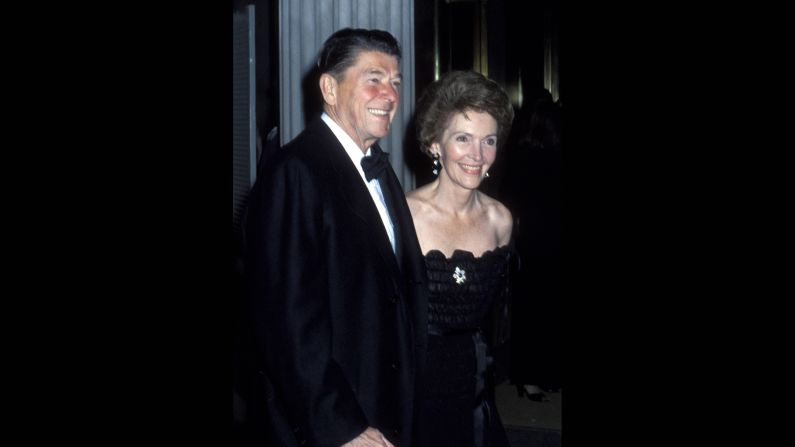

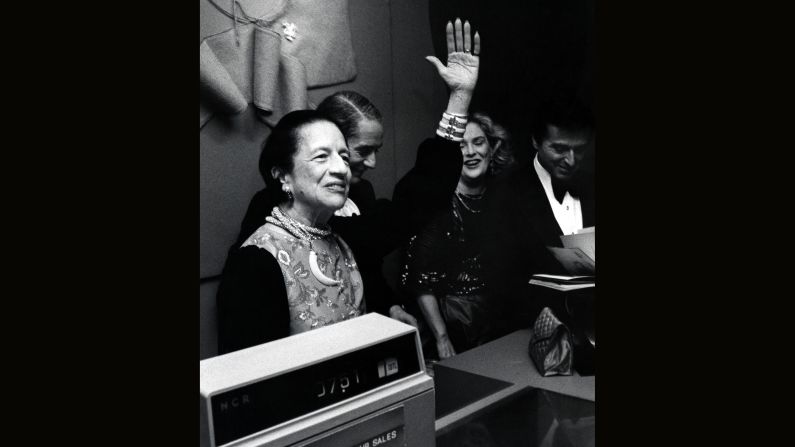

The Met Gala red carpet throughout the ages

Starlets in ostentatious gowns competing for the attention of Anna Wintour and paparazzi have become a requirement for the continued success of the museum. The revenue accrued by the Met gala is what funds the Costume Institute, and the media attention generated is priceless in terms of marketing. But the focus on surface and shine also places the institution in a rather old-fashioned light and makes the whiff of frivolity hard to shake.

In its dated attempts to reduce fashion to sheer surface, the Met is doing itself, and its audience, a disservice. Fashion, whether in its street, high-couture or ceremonial incarnation, is always political. It is high time the Met started reckoning with that.

“Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” is on display at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York from May 10 to October 8, 2018.