Streetwear has always been about more than just clothing. Over the last three decades it has become a global phenomenon, influenced by a DIY, no-holds-barred attitude expressed through fashion, music, art, dance and skateboarding.

And though streetwear has become popular all over the world, different places have their own iterations, including West Africa, where fashion is evolving as young people take streetwear’s history of hip hop and skate culture influences and combine it with local styles to communicate their own realities.

In countries like Ghana and Nigeria, whose youth populations have soared – 57% of Ghanians and over 60% of Nigerians are under 25 – fashion has also become a way for young people to speak their minds and be heard by their communities and the wider culture. Here are some of the most exciting streetwear brands active in West Africa today.

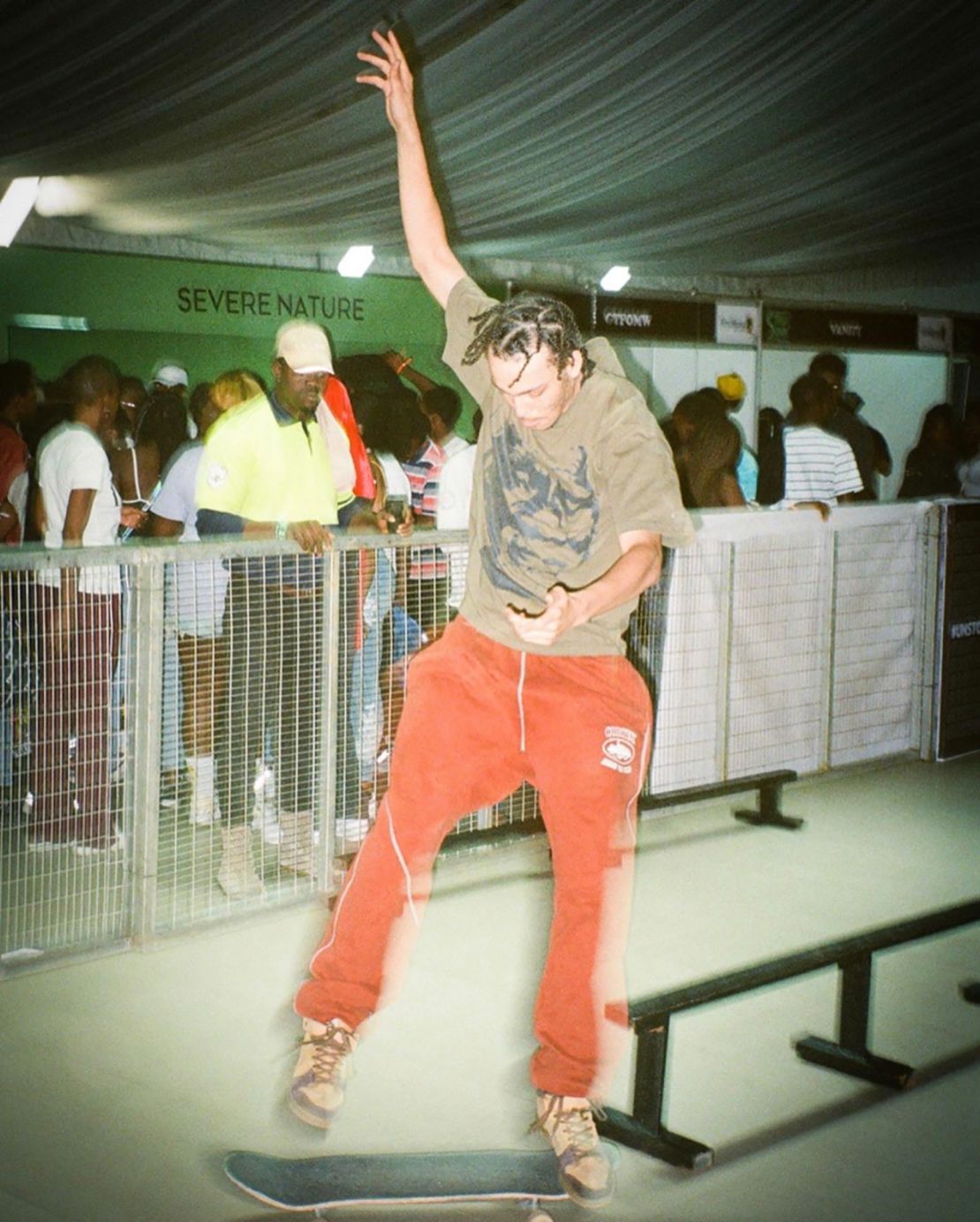

Waffles N Cream

In Nigeria, Waffles N Cream are leading the way in streetwear fashion. “Skate community and family,” is how founder Jomi Marcus-Bello described the brand’s ethos over email. Starting as an online lifestyle brand in 2009, Waffles N Cream has grown into an internationally recognized skate crew, who are also behind Lagos’s first skate shop, established in 2017. “Running a brand in Lagos has its hectic moments but we love it because it’s home,” Marcus-Bello said.

With no designated skate park, skateboarding in a city with nearly 21 million inhabitants and traffic-packed, ill-kept roads is not always easy. But this crew are committed to bringing an authentic Nigerian flair to the culture of skateboarding. This is reflected in apparel made from their own Ankara prints, used to create skate staples including bucket hats and baggy pants – with 10% of sales going towards building that much-wanted skate park.

Vivendii

Fellow Nigerian brand Vivendii, which doubles as a DJ collective, is well-known within Nigeria’s Alté music scene – led by a new breed of genre-bending artists including Lady Donli, Odunsi The Engine and Santi, whose sounds are a distinct fusion of pop and Afrobeat, R&B, soul, dancehall, and hip hop.

“The arts are all intertwined so there are parallels between the way musicians and designers express themselves here,” said Ola Badiru, co-founder of Vivendii, over email. “You know the feeling you get when you connect to certain sounds, we try to emulate that energy in our designs. For example, if pain is being conveyed through the music and we connect to that feeling, we’ll incorporate it – we’ll convey it through the imagery and text on our clothing.”

First launched as a fashion blog in 2011 by Badiru, Jimmy Ayeni and Anthony Oye, Vivendii’s journey was set on course thanks to an influential meeting. “We loved clothes and always imagined creating our own pieces. Then we met (fashion designer) Roberto Cavalli and (former editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia) Franca Sozzani (when they were in) Lagos, and they urged us to create a brand based on our style,” Badiru said. “Our designs are centered around our culture; the way we were raised and the way we live today.” From there, the luxury streetwear brand was born.

Vivendii have collaborated on a project with Virgil Alboh’s Off-White and Nike, for a limited-edition soccer jersey, and their graphic T-shirts and bags have been sported by model Imaan Hammam. Meanwhile, as Vivendii Sound, they’ve Djed for Boiler Room in London, The Voodoo Club in Barcelona, and Afro Nation in Portugal.

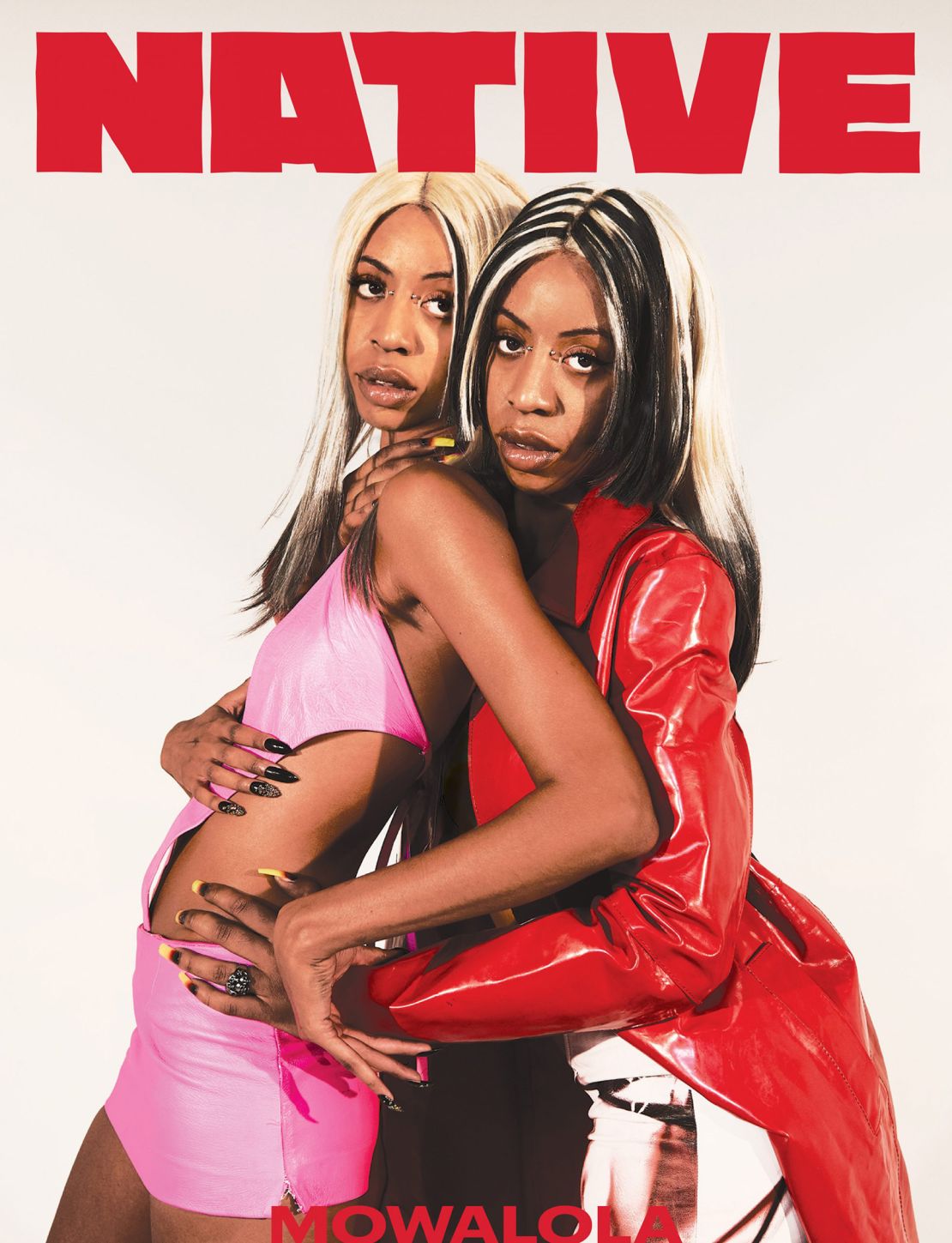

Street Souk and Native Magazine

Young entrepreneur Iretidayo Zaccheaus recognized that there were few dedicated spaces in Nigeria for streetwear brands to showcase and network. As a response to this she launched annual pop-up event, Street Souk, in Lagos. In just two years, the expo has featured over 40 upcoming and established brands, with the next edition due in December.

Meanwhile digital and print publication Native, which defines itself as “the reliable pulse of the African millennial,” ensures a space for youth culture in Nigerian media. Its co-founder Seni Saraki said via direct message that many young people struggle to feel heard or taken seriously.

“I think Nigeria, and this probably extends to West Africa as a whole, is built on the idea that the voices of young people should be lower than that of the elders,” said Saraki. “Even in matters that affect us directly, our opinion is sought last. And this occurs in every industry, whether the creative space, political sphere or legal community.”

Change might be in the air however, with the “Not too Young to Run” bill, which was passed in 2018, offering the chance for younger people to be active in politics. With 18 as the median age in Nigeria, youth involvement in politics and culture could have broad reaching significance.

Free The Youth

A similar feeling of being excluded from national discourse was expressed by Ghanaian Free the Youth brand co-founder Joey Lit. “Before us, the mainstream fashion industry in Ghana was unwilling to acknowledge the youth in terms of job opportunities and consumer engagements,” said Lit over email. “Due to what is considered as appropriate dressing, we were seen as wayward for the way we dressed. A lot of doors were closed to us due to the fact that we weren’t doing what was regarded as the norm”

Established in 2013 by Lit and Kelly Kurlz, and now a 10-strong group, the brand’s collections are driven by stories true to the Ghanaian experience. One design, a screen printed “1000 injured” T-shirt, pays homage to the victims of a stadium disaster in 2001 during a game between the Accra Hearts of Oak and the Kotoko soccer teams.

Since then Free The Youth has made Vogue’s VogueWorld 100 list of boundary pushers, and have done collaborations with Nike, Daily Paper and Foot Locker Europe.

The collective also run the Ghetto University of Tema, a budding NGO in their hometown, Tema, which provides young people with training to develop careers in music production, graphic design, photography and other arts-based paths. “We created this movement in order to empower ourselves and other like-minded youth to embrace that freedom without judgment or reproach,” Lit said.