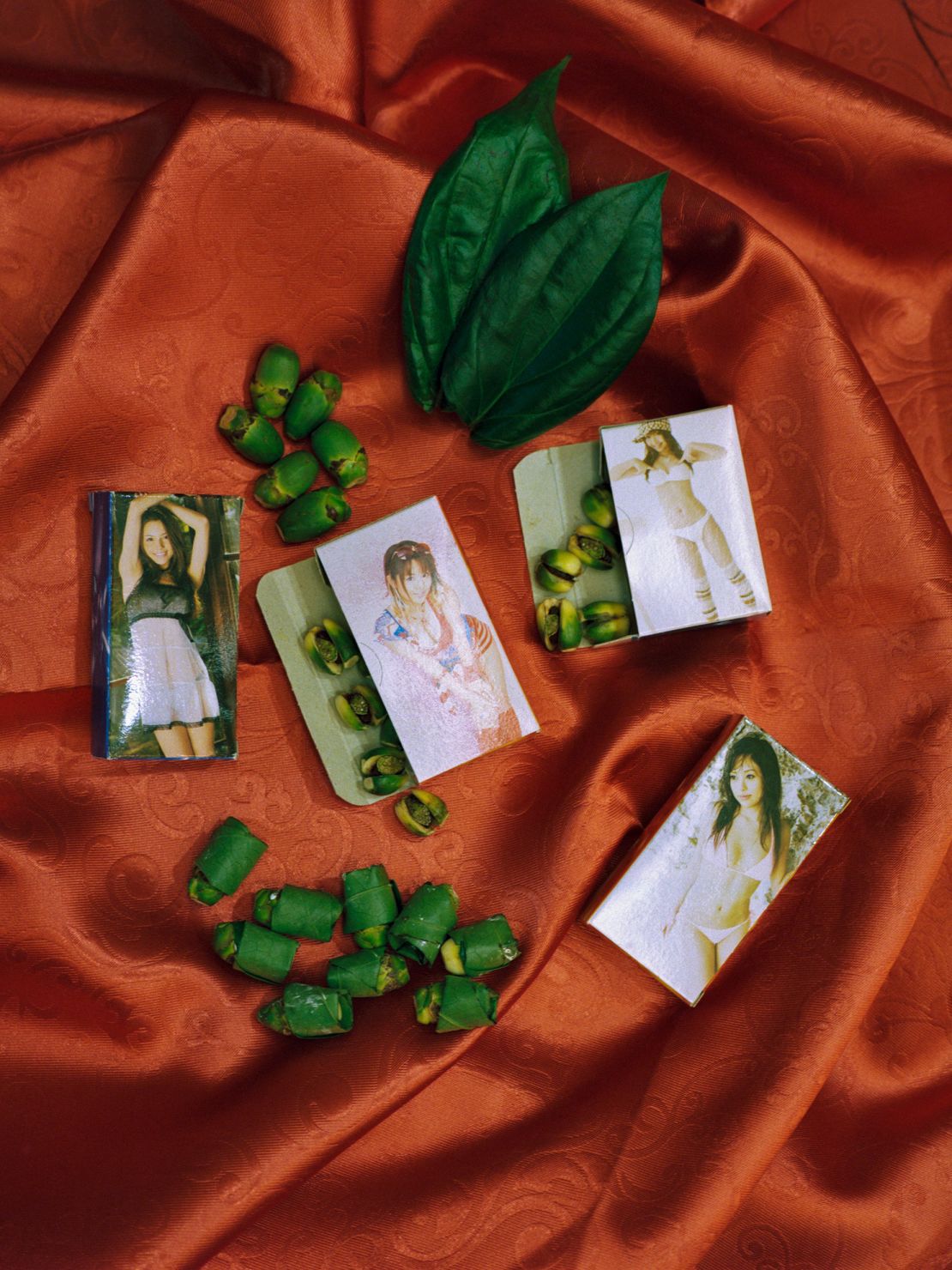

Mong Shuan was just 16 when she turned to an unconventional source of income: selling betel nuts from a little stall in northern Taiwan. The stimulant, a small, oblong fruit derived from areca palms, is chewed by millions of people across Asia. For the next three years, Mong would work six days a week for the equivalent of around $670 a month. A small bonus was tacked on for dressing provocatively to entice male customers.

Her job was to slice the nuts open and add a pinch of slaked lime (or calcium hydroxide, which increases the body’s absorption of the stimulant they contain), before neatly wrapping each one in a leaf. To meet her sales targets, the betel nut “must be delicious.” she told CNN in an email. But hoping to attract more business, Mong would wear her dyed red hair long, a little makeup and a schoolgirl outfit in the style of Japanese anime character Sailor Moon.?“The most important thing is your appearance,” she added.

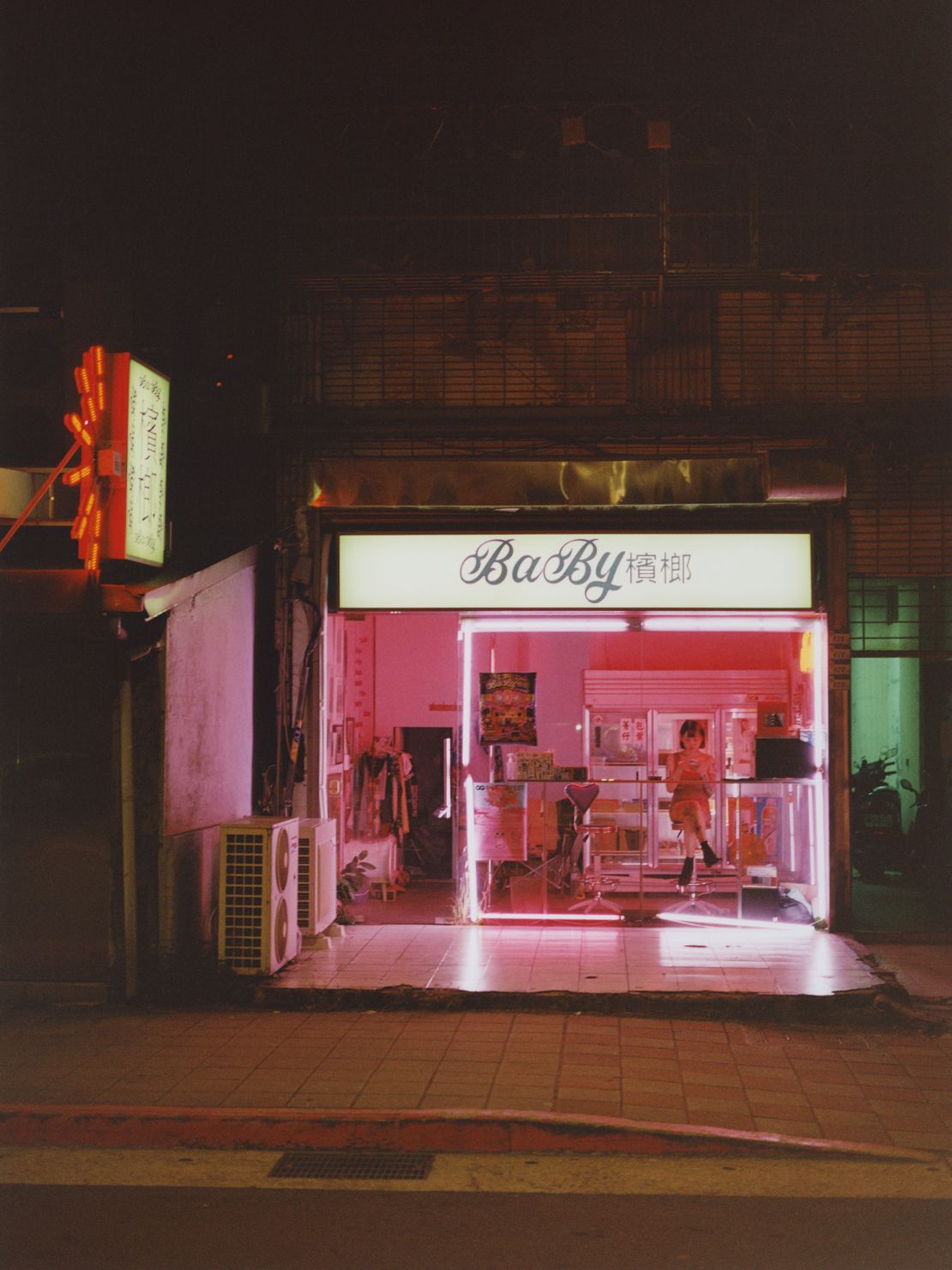

Vendors like Mong, who left the job in February, are known locally as “betel nut beauties.”?The phenomenon emerged in the late 1960s, when the Shuangdong Betel Nut Stand, a stall in rural central Taiwan, successfully marketed their products with a campaign centered on its “Shuangdong Girls.” By the turn of the 21st century, tens of thousands of the neon-lit booths, which dot roadsides and industrial neighborhoods across the island, were staffed by young women.

Hoping to document the phenomenon, photographer Constanze Han spent a month in 2022 driving down the highway connecting the island’s capital, Taipei, to the southern city of Kaohsiung, meeting betel nut beauties along the way. Her fascination with the women dates back to the summer trips she used to make to her grandfather’s courtyard house on the outskirts of Taipei.

“I loved driving there because there were the betel nut girls,” she recalled in a phone interview. “As a child, I didn’t really understand (who they were). My family had been to Amsterdam one time and we’d walked past the red-light district, so I thought it was a similar thing.”

While the scenes of women, scantily clad in glass booths, might resemble brothels, selling betel nuts is not widely linked to prostitution in Taiwan. In fact, the women rarely leave their stalls except to approach drivers in their high heels. Nonetheless, the very existence of provocative betel nut beauties seemed strange in “a quiet, conservative culture” like Taiwan’s, said Han, who hoped her project could help dispel some of the stereotypes the women faced.

“(People with) engrained ideas of respectability, without really knowing or having interacted with these girls, might be like, ‘Oh those are girls from the wrong side of the tracks,’” she said. But in reality, Han added, “they all seemed quite level (headed) and responsible.”

The photographer, who grew up between Hong Kong and New York with stints in Latin America, has always been interested in the jobs women take to survive regardless of the stigma associated with them. She was inspired by the work of Susan Meiselas, whose 1970s photo series “Carnival Strippers,” captured women working hard and long hours performing stripteases at carnivals in New England.

“I always end up gravitating towards women,” said Han, who would spend time getting to know her subjects before asking to take their photos. “The conversation part, where there are no photographs, is such a big part of it. I end up having more honest conversations with women and I feel more curious about the nuances of their experiences.”

Changing habits

Han photographed 12 women, mostly in their late teens or early 20s, apart from one slightly older subject named Xiao Hong, who dresses more conservatively as she prepares the product wearing bright blue gloves at a betel nut stall in New Taipei City. The others appear drenched in the neon light of their booths or are shot gazing out of the windows; one woman’s face is distorted by the reflection of the busy streets outside. The photographer would spend hours capturing small, quiet moments that reveal the job’s mundane nature.

Han’s experience as a former fashion editor comes through in the photos, which often look as if they were staged or taken from the pages of a glossy magazine. But it’s important that her images are “as honest as possible,” she said.

The women would usually arrive for work in their normal clothes and get changed into more revealing garments in the booths, Han explained. Sometimes, owners would incentivize them to dress in a sexier way, though some of Han’s subjects said they would have done so anyway, because it helps them sell more products.

One of the women Han photographed, Ju Ju, is pictured wearing red lingerie as she looks out of her strobe-lit booth in the city of Taoyuan. She began selling betel nuts to help make ends meet, the photographer said, adding that employment opportunities were limited for the young mom, who has no higher education. But Ju Ju has since grown to value the stability of the job. She has now been promoted to a manager position of two booths, and hopes to buy her own stall one day, Han added.

Nonetheless, concerns that the women are victims of exploitation persist in Taiwan, and have prompted some regulation over the past two decades. In 2002, for example, the local government in Taoyuan county implemented a strict dress code that requires sellers to cover their breasts, butts and bellies.

Although it is traditionally served by Taiwan’s indigenous communities at important gatherings, use of the addictive stimulant is also declining sharply. The island’s Ministry of Health and Welfare — which notes that users are 28 times more likely to develop oral cancer than non-users — says that fewer than one in 16 Taiwanese men chewed betel nuts in 2018, down more than 43% from 2012.

As such, Han’s photos document an aspect of Taiwanese life that may eventually cease to exist. She hopes viewers “can look at it as an interesting phenomenon without too much judgement.”

“I hope that (the photo series) opens people up to a different idea of — or a curiosity about — Taiwan as a whole.”