Virgin Atlantic founder Richard Branson once said, “If your dreams don’t scare you, they are too small.” He wasn’t referring to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner that his airline operates, but it easily applies.

On October 26, the Dreamliner reaches its 10-year milestone in service. Branding the 787 the Dreamliner wasn’t just marketing speak. The 787, then and now, is one of those game-changing, envelope-pushing aircraft that come along once in a generation.

It takes its place among legendary earth-shrinking conveyances such as the Douglas DC-3, the first modern airliner; the Boeing 707, the first successful commercial jetliner; The Boeing 747, the first wide-body jumbo jet that brought long-haul travel to the masses; and the Concorde SST. This elite group are considered “moonshots,” deploying cutting-edge, exotic technology often before it was ready. Their paradigm-changing design would influence all new airliners that came after them. But it would come at a price.

By the time the first of the initial batch of 50 787s was delivered to launch customer ANA in September 2011. The Seattle Times reported that development costs exceeded $32 billion. Boeing would break even at over 1,000 delivered units, but this would take another decade. The first aircraft was rolled out in a lavish ceremony on July 8, 2007 (7/8/7), but it had more in common with a mock-up than a flyable plane. It would be another two and a half years before the first 787 took flight on December 15, 2009. It was supposed to enter service in 2008 just prior to the Beijing Summer Olympics. New airline programs are notoriously behind schedule, but the 787’s was three and a half years late.

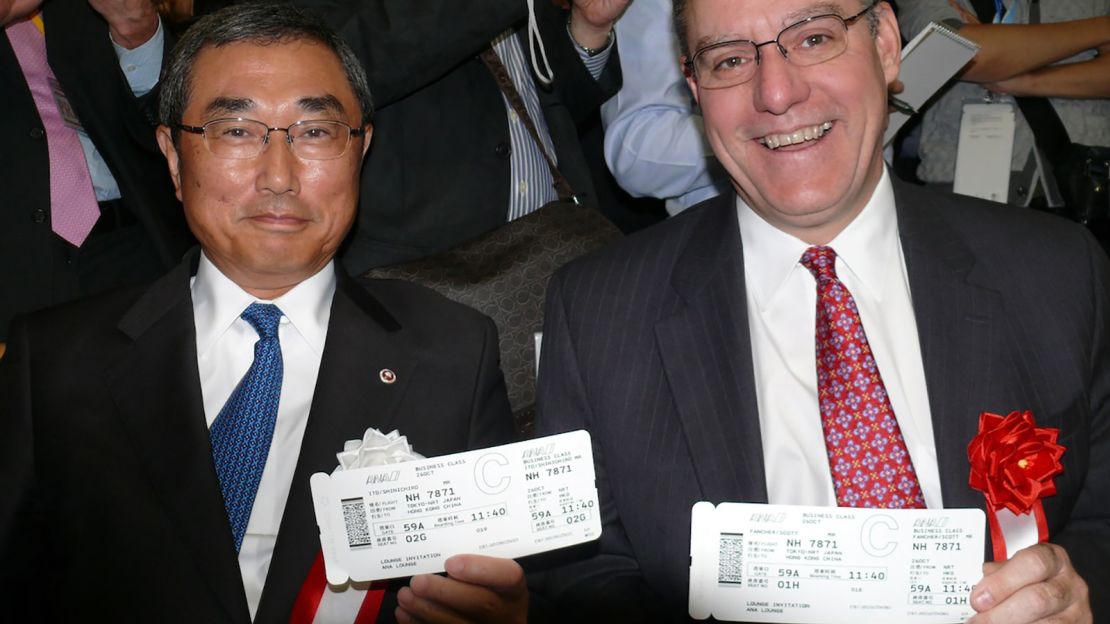

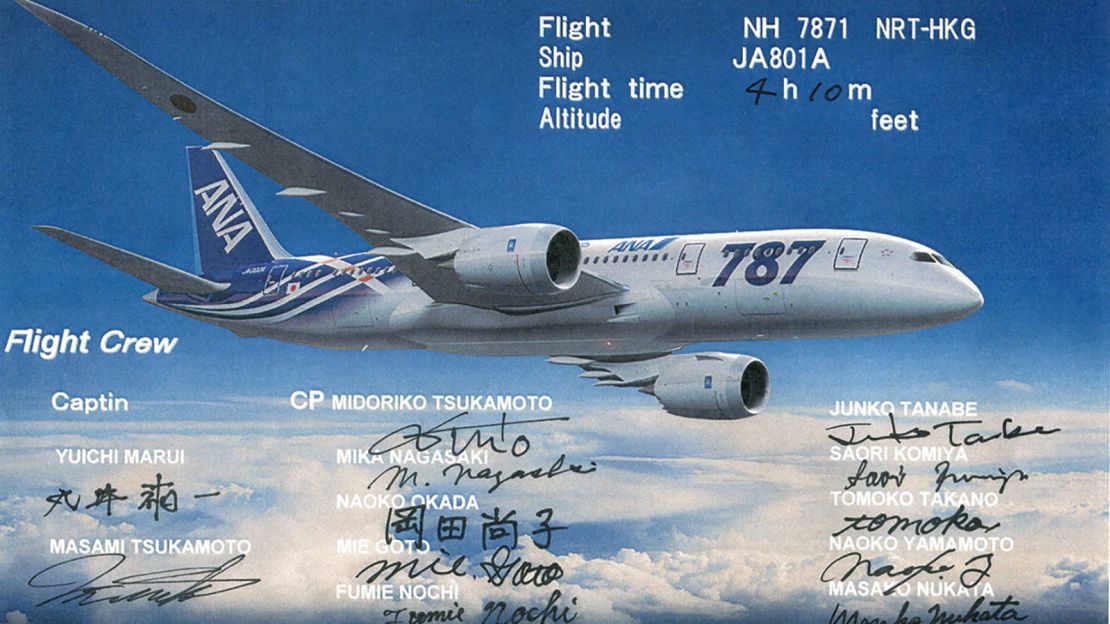

Ten years ago, that troubled gestation was set aside for one historic flight. I was fortunate to be a passenger on board ANA flight 7871, the inaugural flight of the Boeing 787 Dreamliner in passenger service, operating a special charter between Tokyo and Hong Kong. After nearly eight tortuous years in development, Boeing’s technical tour de force was finally ready to the ply the skies for its first customers: airlines and passengers. Our flight’s manifest consisted of media, ANA employees, and about 100 aviation enthusiasts who had competed in an auction for a coveted seat to history. I have covered many first flights, but only the first flight of the Airbus A380 rivaled this for enthusiasm.

Packed with new features

Under banners emblazoned with ANA’s 787 slogan “We Fly First,” ANA and Boeing executives donned Japanese happi coats and led the huge crowd in a kagami wari (sake barrel-breaking) ceremony. Perhaps no one was more excited or relived that this day had finally come than Scott Fancher, Boeing’s sole representative on board and the then vice-president/general manager of the 787 program.

Without getting too geeky, it’s worth recounting what made aviation’s latest arrival such a departure from all aircraft before it. For starters, it was the world’s first all-composite airliner, which resulted in a lighter, stronger, and nearly ageless fuselage. Less weight translates into reduced fuel burn. Major systems such as air conditioning and flight controls once powered exclusively by mechanical hydraulics were now electrically powered. The plane even sounded different, with electric whirrs replacing hydraulic hisses. The manufacturing was highly outsourced and this controversial sharing of financial risk was equally innovative and cost-saving – but ultimately the Dreamliner’s biggest foible.

The 787 delivered gee-whiz passenger experience tech in spades. The passengers on that flight were like real-time beta testers, swarming over all the new features. LED mood lighting programs bathe the cabin in a full spectrum of colors, from calm aquas and radiant reds to full on Studio 54 disco mode. The windows are not only nearly 50% larger than on previous aircraft, but are individually electrically tinted, with no window shades in sight. The natural and LED lighting align the passenger’s circadian rhythm with the light outside and the ultimate destination, thus combating jet lag on the long-haul flights the aircraft was designed for.

Composite fuselages don’t rust, and really don’t age from pressurization and de-pressurization cycles. So instead of a conventional aircraft’s bone-dry 3-5% humidity at altitude, a Dreamliner environment measures more like 25%. Likewise, the cabins are pressurized at 6,000 feet versus the 8,000 feet on more prosaic airliners. These aren’t just gimmicks, but reduce fatigue and increase dehydration and oxygen levels, which matter particularly on longer flights.

A gust suppression system smooths out rough air and improves over time as more real data is collected. We experienced this turbulence-attenuating system on that first flight as we descended into a cloudy Hong Kong. Even the lavatories are high-tech – with touch-sensitive sinks and toilets.

Setting a benchmark

After 4.5 hours aloft, we landed in the history books in Hong Kong to a huge celebration on the ramp with a lion dance, pounding drums, and a brigade of people surrounding the plane.

“The 787 set a benchmark. I don’t even think we fully realized the scope of how much it would change expectations for commercial aircraft,” says Boeing 787 director of product marketing Tom Sanderson, who has been with the program almost since its beginning.

Since that first flight, the 787 has paradoxically been both a dream and nightmare for its customers. It has enabled more than 315 new direct routes, carried more than 559 million airline passengers, and completed more than 2.7 million passenger-carrying flights. Before Covid hit, the 787 was flying more than 1,900 routes worldwide. Boeing’s smaller aircraft vision is the clear winner over the Airbus A380 superjumbo, which Airbus called time on in 2019.

“The 787 did a remarkable job getting people where they really wanted to go. Very few people want to actually go to Frankfurt, and most people who used to go through Narita or Heathrow were actually going somewhere else. This jet took them directly to where they wanted to go, which definitely helped stimulate international traffic,” says Richard Aboulafia, vice president of analysis at Teal Group.

Ecologically, and compared to previous generation wide-body aircraft, the Dreamliner has avoided more than 85 billion pounds of carbon emissions, achieved 20-25% greater fuel efficiency, realized 20-45% more cargo revenue capacity, and produced a 60% smaller airport noise footprint.

The 787 was a resounding sales success as the fastest-selling wide-body aircraft in history, outselling its competitors the Airbus A330neo and A350. As of August 2021, the 787 program had amassed 1,903 orders for its three variants, carrying up to 336 passengers depending on cabin layout, with range of up to 7,530 nautical miles. It has replaced thirsty older aviation stalwarts like the 767 and first-generation Airbus A330s, while hastening the demise of larger A380s, 747s and early 777-200s.

An eye-popping 1,006 Dreamliners have been delivered in just a decade between two final assembly lines at Charleston, South Carolina, and Everett, Washington. The 787 was the first Boeing-designed commercial aircraft ever built outside Puget Sound, Washington, though now it’s only assembled in South Carolina. With more than 80 customers since launch, the backlog stands at 428, adjusted for ASC 606 accounting standards.

“The economics of the airplane were what was needed in the wake of 9/11. The plane proved its value as one of the primary aircraft used as international traffic recovered during the Covid pandemic,” says long-time analyst Scott Hamilton of Leeham Company.

The Dreamliner has been the most utilized wide-body through the pandemic, based on the percentage of its fleet operating versus placed in storage versus its direct competitors. According to Boeing, nearly 90% of in-service 787s have returned to revenue service when compared to pre-pandemic levels (January 2020 vs. August 2021), more than any other commercial airplane type. Many 787 operators utilized their Dreamliners to exclusively carry freight at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, bringing in much-needed revenue as air-freight demand surged.

The dreams nightmares are made of

A little over a year after entering service, in the first two weeks of January 2013, two 787s experienced thermal runaway events with its lithium-ion batteries, one of which resulted in an electrical fire. One of the aircraft flying in Japan was forced to make an emergency landing. The other fortunately had yet to depart from Boston. No passengers were seriously injured, nor were the aircraft significantly damaged. The new plane’s reputation was damaged. All 50 of the world’s 787s operating in revenue service at that time were grounded for over three and a half months. Once modifications were made to the battery cells, there have been no serious mishaps since.

Vendor, supply chain, and manufacturing issues, particularly with the composite fuselage, had bedeviled the 787 in its early days of development, but have surprisingly reared their head again years later. Ignominious for such a mature program that peaked at 14 aircraft rolling per month rolling off dual assembly lines.

Current 787 deliveries have been mostly suspended over the last year because of quality control programs involving microscopic tolerances of fasteners joining fuselage barrels together, and additional issues with electrical systems and windscreens. This has resulted in around 100 undelivered 787s subject to rework. The company’s cash flow has been impacted by the billions, and turning the once profitable program on a unit basis into a big money loser once again. Once delayed these undelivered airframes are subject to cancellation by their customers, and significant compensation.

The 737 MAX and 787 problems have only fed off each other. “Had the MAX crisis not happened, I suspect the delivery suspension would have been short-lived, if occurring at all,” says Hamilton.

Hamilton believes the 787 program has cost an estimated $50 billion in program development, cost overruns and customer compensation. And what’s overlooked is the knock-on effect in product development. “Had the 787 been delivered on time, Boeing would have easily been 5-8 years ahead of Airbus. Boeing’s distraction by crisis after crisis has given Airbus a commanding lead in the heart of the narrow-body market.”

Boeing’s Sanderson isn’t defending the delays, but stresses that “All 787s in service and in our inventory are perfectly safe to fly.” The planemaker sees a silver lining with learnings applied to build even better 787s and new aircraft like the next-generation 777-9.

Dreaming of the future

The prospects for the future of the program are generally positive. Hamilton concedes “The 787 is a good airplane” and sees it being further improved with new technology, such as new engines as with past Boeing programs.

Aboulafia sees the biggest threat to the 787 as, ironically, the fragmentation that drove its success: “The biggest risk to future 787 orders is new, more capable single-aisle jets, particularly the A321 Neo. Just as the 787 helped destroy the business case for larger jets like the A380, new more capable narrow bodies are making the case for thinner routes.”

Boeing’s Sanderson is buoyant, making the case that the 787 is well positioned for new orders during the post-Covid recovery as airlines begin growing again and replacing older aircraft over the next twenty years. “We’ve got decades of life left in the program. The structural piece of the airframe is not the thing that will take it out of economic service. There may be modifications and upgrades and things that we might not have considered on older metal aircraft that might make good sense for the 787. We’ve never had an all-composite airplane reach the end of its economic life yet.”