Story highlights

The red telephone box exudes a sense of nostalgic familiarity and British cool

Over 90 years old, the classic phone boxes have found themselves unused

Community-based efforts are revitalizing the vintage boxes

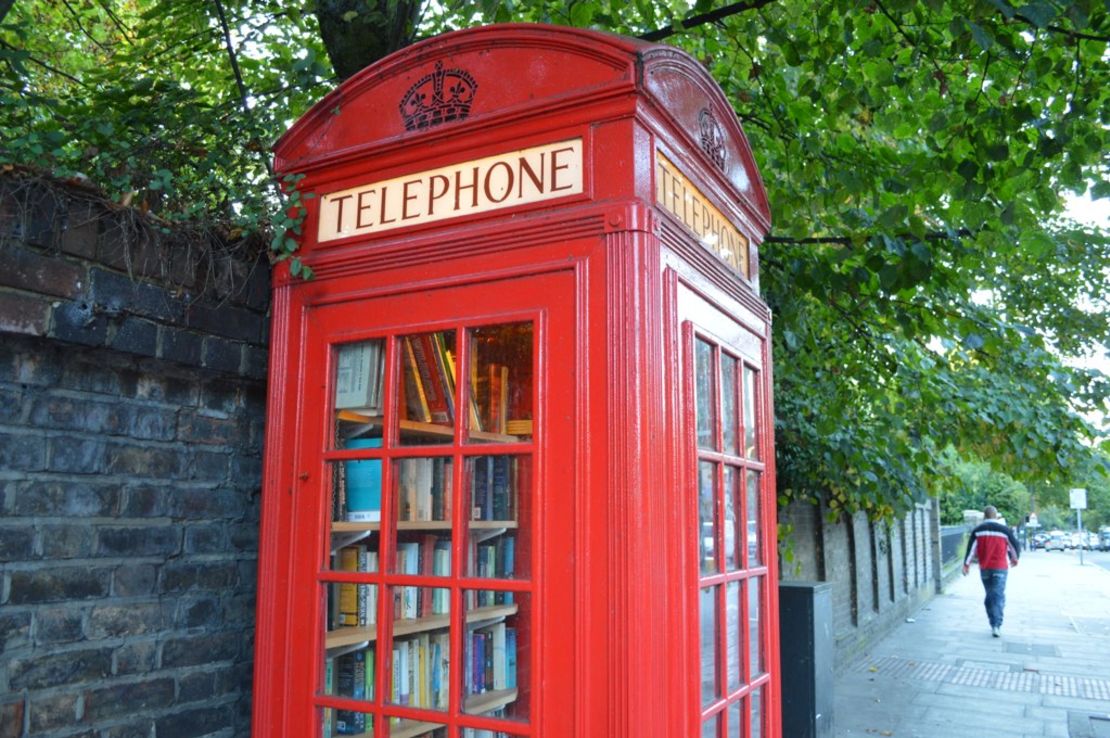

From its pillar box red, cast iron exterior and domed roof to its crown insignia and paneled windows, the red British telephone booth is a universally recognized icon.

Giles Gilbert Scott’s famous design was first introduced following a competition in 1924, with variations appearing across the country, from London street corners to remote villages.

More than 90 years later, the phone box is a popular backdrop for thousands of selfies, but thanks to the ubiquity of smartphones, these British classics are becoming obsolete.

Some, however, are being preserved as entrepreneurs and communities re-purpose them as unexpected places to swap books, buy coffee or even enjoy a meal.

British cool

Though the phone boxes may not have been used by millennials, they’ve long been a part of pop culture in the UK, having been immortalized on the back cover of David Bowie’s “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” album.

Nigel Linge, Professor of Telecommunications at the University of Salford and author of The British Phonebox suggests it’s all about the aesthetic.

Giles Gilbert Scott brought a design which captured people’s imagination, he says.

“It was so different, it just looked dramatic on the street, in terms of how it appeared, with the windows, the domed roof, the red color.”

Adopt a phone box

Recognizing their cult status, UK telecommunications company British Telecom introduced an “adopt a kiosk” program, encouraging communities and businesses to buy red phone boxes for £1 (less than $2) and give them a new lease of life.

Among them were two on the pier of the southern English seaside town of Brighton, which were spotted by locals Edward Ottewell and Steve Beeken.

“They were empty and run down and we thought we could sell sunglasses from the phone boxes and hats from this great location,” says Ottewell.

The duo regenerated the Brighton kiosks and then formed the Red Kiosk Company with a plan to adopt 500 phone boxes across the country.

They helped Londoner Umar Khalid transform a phone box near Hampstead Heath, a large area of parkland in the city’s northern suburbs, into a thriving cafe, Kape Barako.

Khalid says his kiosk is regularly photographed, making numerous appearances on Instagram and Facebook.

In the summer months, Londoners can also enjoy Spiers Salads in central Bloomsbury Square. In Birmingham, the UK’s second-largest city, locals praise Jake’s Coffee Shop.

Phone boxes = community

Phone boxes are often associated with Britain’s capital, but they can also be spotted in the country’s more rural areas.

In the Scottish hamlet of Marywell in Ballogie, bordering the Cairngorms National Park, the community has converted its local phone box into Scotland’s smallest Internet cafe – a digital oasis in the Scottish Highlands where 3G and 4G phone signals are hard to find.

The Ballogie phone box dates from the 1940s and neighbors the Butterworth Gallery, run by Sarah Parker.

Parker had the idea of connecting the WiFi from her gallery to the phone box and adding a hot drinks machine.

“It had to be repainted, we had to seal all of the panes, it was leaking quite badly,” Marywell resident David Younie says, adding that it’s helped bring residents together and has become a focal point in the picturesque hamlet.

Occasionally residents take the coffee machine out of the phone box. Not because of fear of burglary, but because they worry the water might freeze.

Lending library

In a suburb of southeast London, another community came together to transform a phone box into the successful Lewisham Micro Library.

“Just the fact that you might be using it at the same time as someone else means you’re talking to people who would be total strangers otherwise,” says local “librarian” Susan Bennett.

The Lewisham phone box is beloved by the local residents, and initial fears of vandalism have proven unfounded.

“Generally it’s in good order because people want that,” says Bennett.

Working on the go

Pod Works is another company set up to convert telephone boxes, this time into mini work stations for commuters and tourists.

Its booths are decked out with printers, a 25-inch screen, a powerbank of plugs and a hot drinks machine.

Pod Works believe it’s the future of mobile working.

People sign up to be members, book slots at pods across cities and get sent an access code for their chosen kiosk.

“At the moment the phone boxes are derelict, they are becoming a bit of an eyesore. We wanted to re-purpose them for the 21st century,” says Lorna Moore, managing director of Pod Works.

Keeping the heritage

Two new types of modern, sleek phone kiosks will adorn British streets in 2017.

British Telecom has introduced a Links kiosk, a screen featuring advertising and information and WiFi, while World Pay Phones will introduce a screen which incorporates the iconic domed roof.

“The phone box has evolved, it’s still an access to telecommunications service, but of course the nature of those services has changed dramatically,” says Linge.

While some orignal red booths are protected as historic treasures, Ottewell worries others will simply be removed to make way for the new kiosks, leaving future opportunities for reinvention unlikely.

“We want to protect and save as many as we can,” he says. “It’s going to create employment, it’s going to regenerate an area that’s been left, and do some good.

“We want to protect our heritage.”