“No moon, no blossom. Just me drinking sake, totally alone.”

This melancholy haiku was penned by Japanese poet Matsuo Basho in 1689, shortly before he set off on a 1,200-mile journey through Tohoku, Japan’s vast northeast that reaches up to Hokkaido.

The trip is remembered in his celebrated travelog, “The Narrow Road to the North,” a classic of Japanese literature.

A modern riff on the bard’s journey might take in the region’s hundreds of sake breweries – many of which are producing some of the best sake in Japan.

Whether a sake tour will lead to inscribing timeless haikus is another matter.

Award-winning sake

Where to find the world's best sake

The Tohoku region, led by sake brewers from Fukushima Prefecture, has been piling up gold medals at the Annual Japan Sake Awards for a number of years.

“Tohoku has the highest reputation for sake in the country amongst people in the industry,” says John Gauntner, a sake expert and author of numerous books on Japan’s national drink, including “Sake Confidential.”

At the annual sake award ceremony, convened by Japan’s National Research Institute of Brewing, hundreds of sake brands from breweries throughout Japan are rated and judged.

For 2018, judges awarded breweries from Tohoku’s six prefectures a total of 69 gold medals out of a national total of 232 in 37 prefectures.

Melinda Joe, a Tokyo-based journalist and a sake judge and panel member at the International Wine Challenge – a separate sake-tasting competition – says that sake from Tohoku is characterized for having a light, clean and elegant style.

“Tohoku sake has a little more voluptuousness – a little more to give,” says Joe.

Part of what makes Tohoku’s sakes so different is geography: The winters are severe with heavy snowfalls and historically, because of its remoteness, agriculture has been the mainstay in Tohoku, explains Hiromi Iuchi, an official at the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association.

The region has long produced huge quantities of sake, says Iuchi, but in the past few decades a shift has been underway to improve brewing techniques.

This has been led by an association of master brewers called the Nambu Toji, located around Tohoku’s Iwate Prefecture.

Such is the influence of this group that toji (brewers) from western Japan are taking note of what their counterparts in Tohoku are doing, Iuchi adds.

Sake expert John Gauntner says the colder temperatures in Tohoku influence production and taste.

“Tohoku breweries have always had colder weather and so they can ferment, produce and store at lower temperatures which, among other things, gives the sake a very light, delicate, refined and elegant flavor profile compared to the rest of Japan.”

Kenichi Ohashi, one of the foremost sake experts in the world as well as a co-chair of the International Wine Challenge, says sake from Tohoku is notable for its aromatic qualities.

“Personally I like a lot of the sake makers in Tohoku – it’s one of the things that makes Tohoku attractive for me.”

Which bottles are the best?

Ohashi singles out Mutsu Hassen from Hachinohe Shuzo Sake Brewery in Aomori, a trophy winner at the 2016 International Wine Challenge.

“It has a good mid-palate weight, but is very perfumed,” says Ohashi, while also praising the beautiful label, which incorporates images of the trawlers that plow the seas around Hachinohe at night fishing for squid.

One other sake Ohashi recommends is the award-winning Yamawa sake from Yamawa brewery. Although it sounds counterintuitive, Ohashi praises Yamawa’s water-like qualities.

“Japanese people tend to pay a lot of money for the water-like taste, as with fugu (pufferfish).

“This sake is all about texture and not about umami – it’s a very pristine and transparent sake, it’s like high-quality water.”

How to experience your own sake safari

For visitors making the trip north, several breweries offer tours in English, as well as tasting, but you will need to book in advance via their websites.

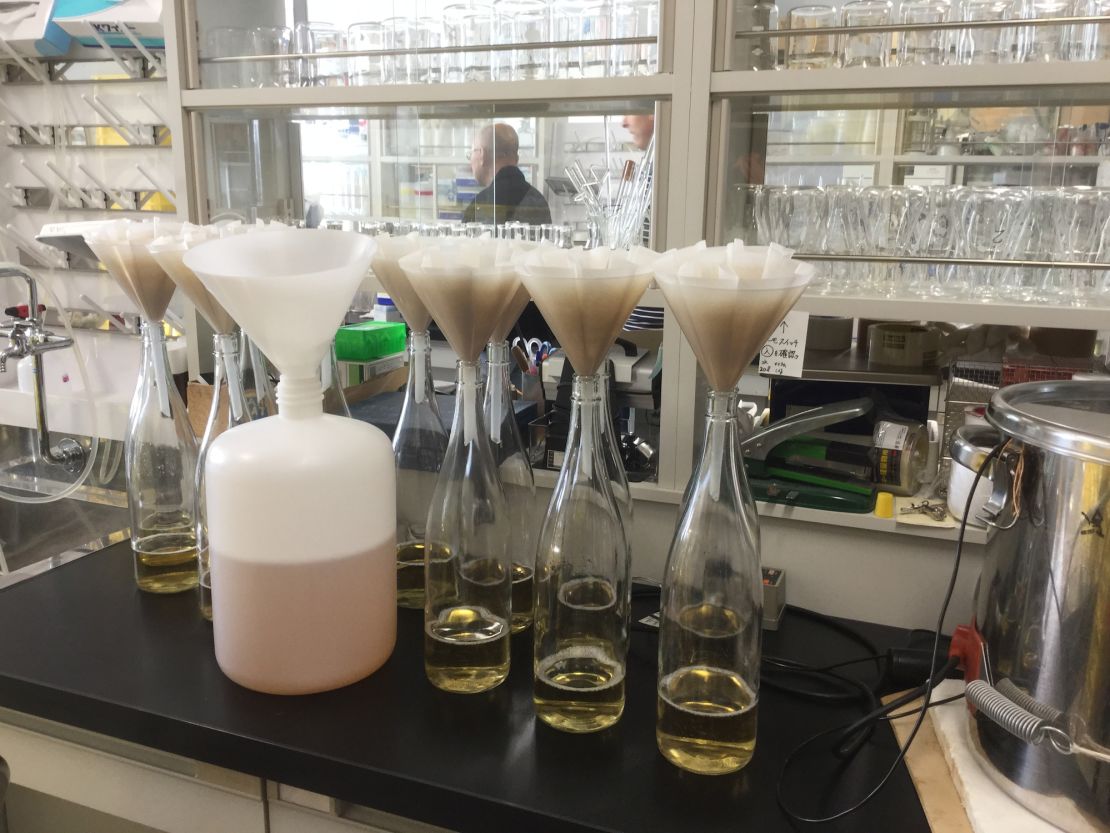

Daishichi Brewery, founded in 1752 in Fukushima, is unusual in that it still adheres to the kimoto method of brewing, a labor-intensive method that has largely been abandoned in favor of modern technology.

“The reason Daishichi has kept this kimoto method is that it leads to a certain type of sake,” explains Ad Blankenstein, director of overseas sales and marketing at Daishichi.

“Sake which has body and a rich taste and, which in fact, is more like red wine than white wine and which can be paired with creamy dishes, with meat, French dishes … food with stronger tastes.”

Remote Senkin Shuzo, a family-owned brewery in Iwate, has been making sake since 1854.

Yuri Yaegashi, one half of the current ninth-generation owners, recommends a brewery visit to the limestone-rich area in early summer or fall.

While Ryusen Yaezakura is Senkin Shuzo’s award-winning sake, Yaegashi also recommends Mori no Takara, made with matsutake mushrooms, a local delicacy grown in Iwaizumi.

“Matsutake are very special mushrooms for Japanese that evoke nostalgia,” says Yaegashi. However, the aroma can be a little challenging.

“Some people said it smells like socks,” adds Yaegashi.

Further north, Takashimizu Brewery in Akita also welcomes visitors.

Its award-winning Takashimzu sake brewed at its Goshono brewery strikes a balance by offering both a gentle fragrance and a refined taste, according to Yukiko Takahashi of Takashimizu.

“It’s the type of sake that can accompany almost any meal, owing to its delicate but refined character,” Takahashi adds.

This article was originally published in 2016. It was updated in October 2018.

JJ O’ Donoghue is freelance writer based in Kyoto, Japan.