Captain James Basnett is at the controls of a British Airways Airbus A380 mega-jet, serenely cruising far above the stormy North Atlantic.

More than 450 passengers are enjoying the inflight service, watching a movie or just sleeping away the overnight flight from Boston to London.

Comfortably cocooned in the technological marvel that is a modern airliner, the passengers are blissfully unaware that their plane is just one of hundreds in a massive aerial armada heading to Europe from North America.

Every night, this incredible formation of aircraft flies eastbound across the Atlantic. Then, just a few hours later, the flights head west, carrying thousands of passengers bound for airports in the United States, Canada and beyond.

How does Basnett manage to navigate through the stratosphere and keep his A380 safely away from other flights as they travel?

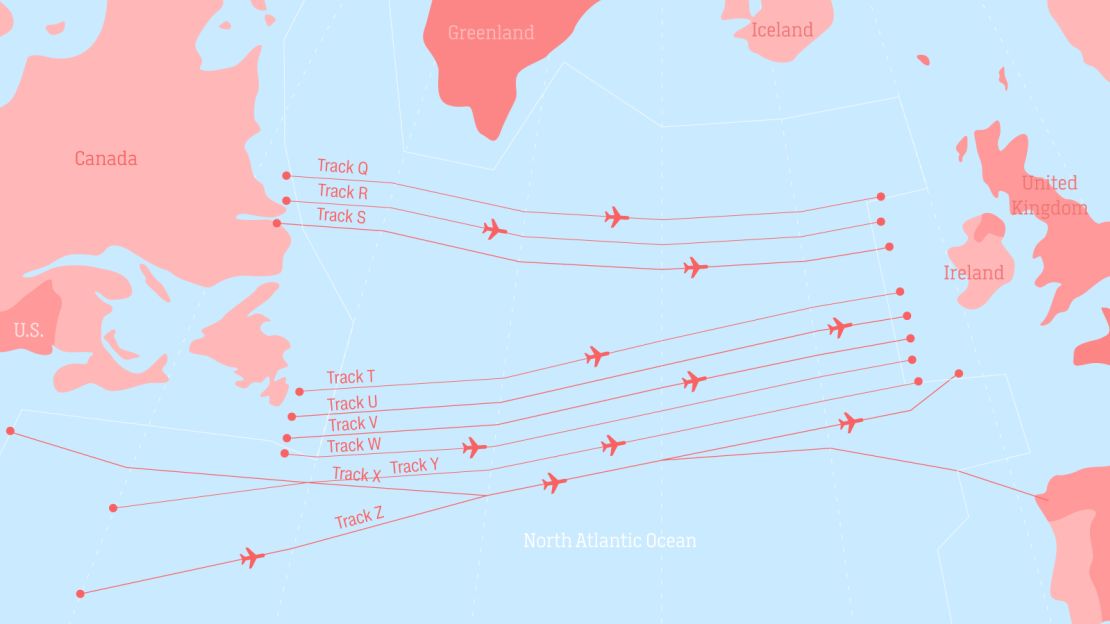

Skyways across the ocean

Looking like a matrix of skyways across the ocean, the North Atlantic Organized Track System (OTS) is a set of virtual aerial highways that are created and managed by the bordering air navigation system providers – NAV Canada, and NATS in the UK – with coverage split halfway across the ocean.

The tracks are dynamic, rarely the same day to day, and can be vastly different eastbound and westbound. Based on a latitude and longitude grid, each skyway is distilled down to a single line, crossing the Atlantic.

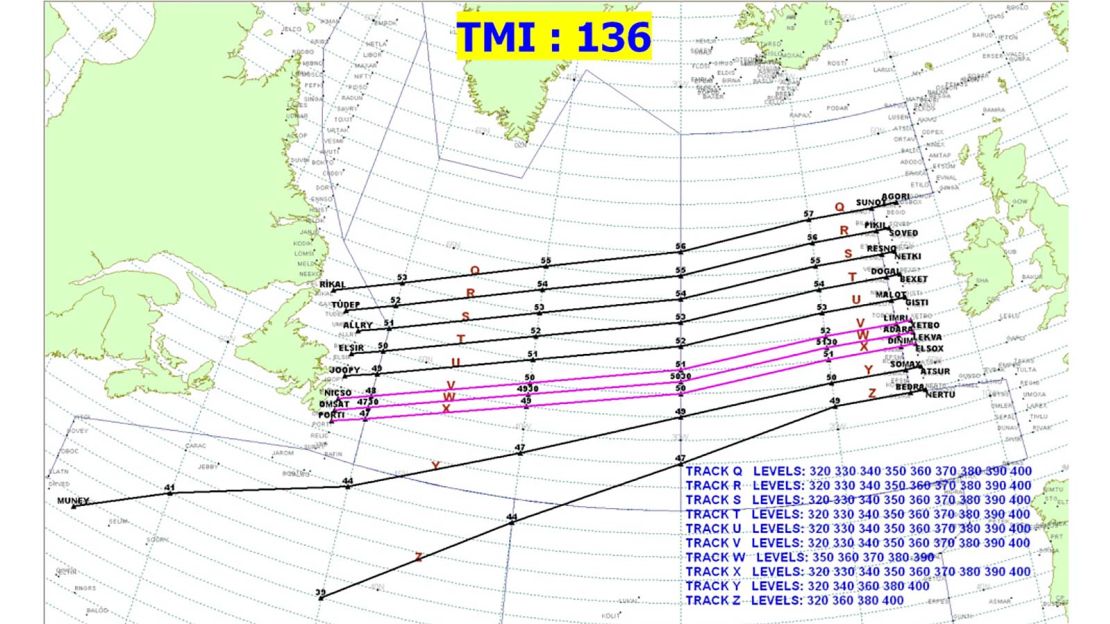

Daily, at 7 a.m., in NAV Canada’s Area Control Centre in Gander, Newfoundland, an oceanic planner reviews information supplied by airlines that outlines the day’s flights, along with requests for preferred routes and cruising altitudes.

Then, using sophisticated computer modeling, a series of eastbound skyways are created for the evening’s flights that depart from North America, 12 to 14 hours later.

At about the time those flights head for Europe, the NATS team in Shannon, Ireland, and Prestwick, Scotland – known as “Shanwick” – begin work on the day’s westbound tracks, using similar procedures and processes.

Riding the jetstream

“Our systems have all the meteorological models, including the winds at various levels,” Jeff Edison, NAV Canada’s Gander Area Control Centre Manager, tells CNN Travel.

Eastbound tracks are optimized to take advantage of the tailwinds provided by the jet stream, the globe-circling, fast-flowing river of air that can reach speeds above 200 mph (322 kph).

“For example, if the jet stream goes straight across the Atlantic, without any zigs or zags, we’ll create a track that’s right in the center of it. Every flight is going to want to fly on that track, but not everyone is going to fit,” said Edison.

“Sometimes it means spreading the benefit of that eastbound tailwind over two or three tracks. We call those the core tracks.”

Typically, five, and as many as 14 tracks are created every day. They’re identified simply with a letter.

Z – for Zulu – is the southernmost eastbound skyway, then Y, X, W, and so on, until all the day’s tracks are labeled. The tracks can span from 300 to 700 miles (480 to 1,130 kilometers), north to south, depending on the weather.

Westbound tracks are designed to limit headwinds by avoiding the jet stream. Track A – for Alpha – starts in the north, and the rest of the skyways are lined up southwards from there.

To get onto the correct track for his flight, Basnett flew northeast from Boston. Communicating with air traffic control (ATC), his A380 was sequenced to reach a fix – a point in space – that was the entry point for his flight’s designated track.

There’s a long line of navigation fixes on both sides of the Atlantic, and these serve as entry and exit points for the tracks. Each is identified with a five-letter word that’s pronounceable, but often nonsensical. JOOPY and IBERG are two fixes off the coast of Newfoundland, while MOGLO and LEKVA are near Ireland.

Safety box

Once the A380 heads out over the Atlantic on its specified track and altitude, it cruises in the center of an imaginary box, to make sure it’s safely away from other planes.

“Before being accepted on an Oceanic Track, we must ensure that our instruments and navigation systems comply with the stringent requirements that ensure the most accurate separation of aircraft,” says Basnett.

With the recent introduction of advanced navigation equipment and procedures, aircraft on the OTS cruise five minutes’ flying time behind the preceding plane, which is about 40 miles. Laterally, there’s a 25-mile separation from the closest plane on either side, and a 1,000-foot safety zone above and below.

These separation rules also apply to aircraft that fly against the flow, such as cargo planes traveling to Europe during daytime.

“As a safety precaution, we geographically separate their routes from the OTS. However, there are times when a random eastbound flight meets a random westbound flight for a segment of their flights. They’re separated by a minimum of 1,000-foot altitude,” explains Edison.?

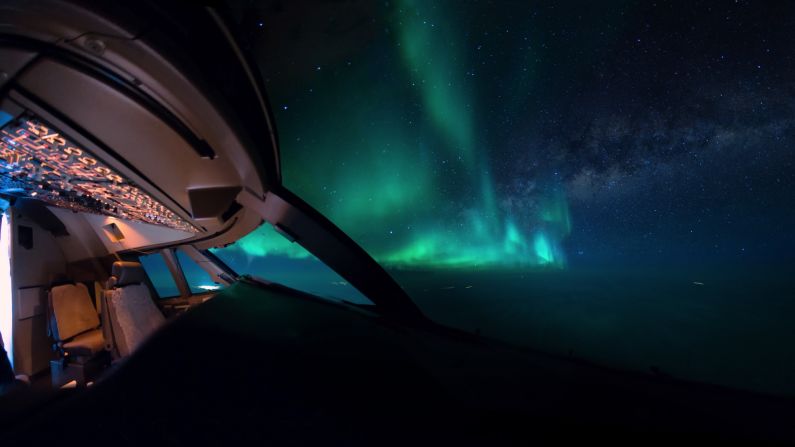

With so many planes flying in a giant loose formation, the view out the flight deck windows can be the “best seat in the house.”

“Contrails, which are water crystals formed from condensed exhaust vapor, can be seen miles away during the day, and navigation lights are highly visible at night,” explains Basnett.

“Needless to say, observing a large aircraft such as an A380 traveling 1,000 feet above you in the opposite direction with a closing speed of over 1,000 mph is an impressive sight!”

Pilot's spectacular photos taken from an airplane cockpit

Communication

Out over the ocean, crews and controllers can talk to each other over high-frequency radios, but most communication goes through a secure satellite-data link.

Every 14 minutes, each flight automatically sends its position information. A position report is also required when a flight crosses every 10 degrees of longitude. Crews will also use the data link to make requests for altitude or track changes, perhaps if it’s a bit bumpy.

“Sometimes, just changing the aircraft’s altitude by 1,000 feet can improve matters, or by not flying on the edge of a jet stream, which can sometimes feel like a cobbled street,” said Basnett.

Pilots flying the OTS also chat with each other on a common radio frequency, something like a plane-to-plane party line, according to Basnett.

“We discuss ride [turbulence] reports or anything of interest with other pilots in our area. When things are very quiet – and bizarrely feeling quite lonely despite nearly 500 [people] on board with you – discussions can sometimes extend to the latest baseball scores, which often gets a multitude of responses and gags, particularly from American pilots.

“A request for cricket scores normally [has] a very reserved one-line British response.”

So, after checking the cricket scores, and reaching the eastern end of the OTS, Basnett’s A380 and the hundreds of other planes fan out, safely conveying passengers to their destination airports.

It’s been just another night over the North Atlantic.

![<strong>Painting a picture: </strong>"The pictures I take, let's say they are the tip of the iceberg," van Heijst says. "But many of the pictures are either shaky or blurred [...] but I think overall, my pictures, they give a pretty clear image of what it is like to fly." <em>Pictured here: London city lights and clouds.</em>](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/180108102728-london-citylights-night-clouds-cnn.jpg?q=w_2000,h_1125,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)

![<strong>Willingness to fail: </strong>"It takes a long breath, a lot of effort, and willingness to fail very often [...] you will encounter situations where it's frustrating you couldn't capture it, but persistence, that's the best word to describe it," says Van Heist.<em> Pictured here: Aurora sunrise over Canada.</em>](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/180108102330-aurora-sunrise-stars-canada-cnn.jpg?q=w_2000,h_1125,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)