On October 1, 2000, the skirts of Princess Anne and Princess Margaret deflated for the final time. These two colossal SR.N4 hovercraft had shuttled vacationers and booze cruisers between the UK and France since the late 1960s. Now it was time to say au revoir.

What prompted their retirement? Plenty. Passenger capacity was less than a quarter of the average ferry. These “Mountbatten” class hovercraft were spendy to run; after each trip, their Rolls-Royce gas turbines – normally used on aircraft – had to be rinsed with distilled water.

The opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 didn’t help. Neither did the scrapping of duty-free booze and cigarettes, which had always heavily subsidized the service between the English port of Dover and Calais and Boulogne in France.

It was the end of the British hovercraft era. Except it wasn’t. Because 100 miles east of Dover, another hovercraft service refused to let go.

‘The kids’ faces light up’

On a blistering June morning in Southsea, on the south coast of England, the “Island Flyer” is puffing up like a bullfrog, fans whirring, beach shingle spewed in its wake.

It’s peak time on Hovertravel’s Southsea-Ryde route; every 15 minutes passengers are jetted across the sparkling waters of the Solent, slaloming sailboats before gliding up onto the Isle of Wight slipway less than 10 minutes later.

Small crowds of onlookers group on a nearby footbridge – phones poised – to greet it, like some minor celeb.

The Southsea-Ryde route opened in July 1965. There was no timetable back then; the old 38-seat SR.N6 craft simply fired up their engines once enough passengers were waiting. There were no dedicated slipways either; vintage film footage shows hovercrafts belly-sliding onto busy beaches, to the amusement and bemusement of sunbathers.

Even today, you might miss Southsea’s unassuming hoverport; the small, pitched-roof building is part of a short parade with a fruit stall, ice cream parlor and fish and chip shop.

Yet 56 years on from its launch, this remains the only year-round commercial passenger hovercraft service in the world. A community-minded team of managers, engineers and pilots (more of which later), keep things running. Up to 78 passengers board at a time; off season, most are island commuters working on the mainland but come summer, the hovercraft is one of the area’s big tourist attractions.

“The kids’ faces light up,” says Hovertravel duty manager Terri Frost, who oversees operations on both sides of the water. “It’s just really great that you’ve been part of their day, even if it’s just that 10-minute crossing, you’ve made their day.”

Hovercrafts aren’t just special to kids, either.

“There’s a gentleman who comes for the Isle of Wight Festival,” Frost says, “He comes from Australia and he only uses the hovercraft because he loves it.” Japanese tourists are also known to come out of their way to marvel at these oddball amphibious craft.

Perhaps part of people’s love for the hovercraft is its sense of near-sentience; the way they swell and deflate as if breathing. The “Island Flyer” and “Solent Flyer” even joined nationwide applause for UK health workers in 2020 – the bottoms of their skirts slapping on the concrete pads at Ryde.

Altogether, Hovertravel’s route clocks up just under a million passengers a year. So where did this service succeed where its bigger international cousin didn’t?

Hovercrafts don’t run on nostalgia and novelty alone

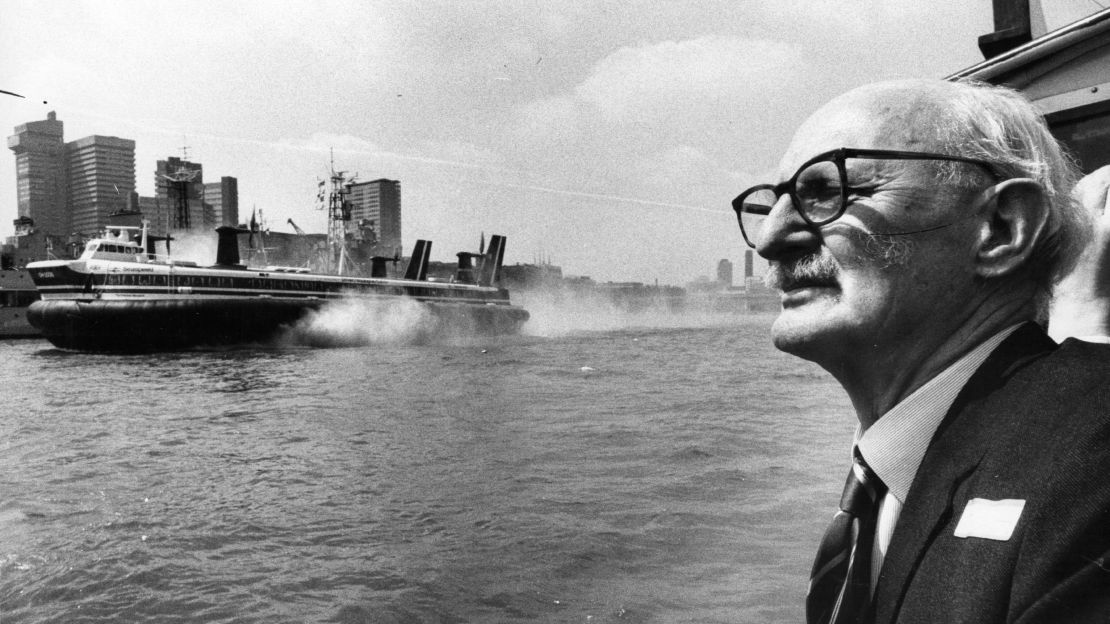

“He was a fairly quiet guy, not bubbly, but I would describe him like myself. A bit of an anorak,” says Alan Barkley, a volunteer at the Hovercraft Museum at Lee-on-the-Solent, half an hour’s drive from Southsea’s hoverport.

The anorak – British slang for someone with an obsessive interest – he’s talking about is Christopher Cockerell, inventor of the hovercraft.

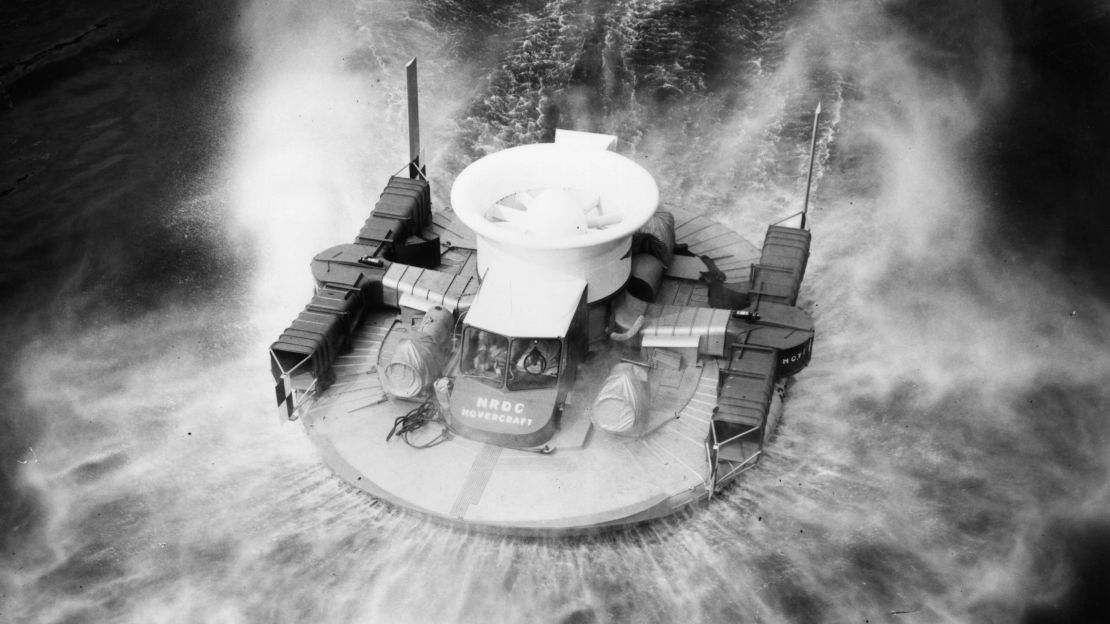

The story goes that Cockerell made his prototype using a can of cat food, a coffee tin and a vacuum cleaner, before launching the real deal off the Solent in 1959. A fearless pioneer, Cockerell also took the hovercraft on its first ever Channel crossing – bravely pacing around the outside of the SR.N1 for the duration of the voyage, acting as “dynamic ballast.”

Choosing coastal Hampshire for much of the testing – not to mention building hovercraft at Saunders-Roe in Cowes – Cockerell essentially turned the Solent into “Hover Country,” and it never really looked back.

The museum is a fascinating shrine to various iterations of Cockerell’s creation: there’s a craft used in the last Iraq war; one from the 2002 Bond film “Die Another Day;” a cute contraption made with the chassis of a Mini. This afternoon, one of the former Princess Anne cabin crew is celebrating her 50th birthday aboard the craft, which is now cared for by the museum.

“The hovercraft was built in the area, invented in the area, and I think that’s got quite a bit of influence on why the Isle of Wight craft is still running successfully,” says Barkley.

But hovercrafts don’t run on nostalgia and novelty alone; there has to be a genuine need for it. In the Isle of Wight’s case, Ryde’s pier juts half a mile out to sea, so even once you’ve made the (slower) ferry trip over from Portsmouth, there’s still a bit of a schlep to dry land. The dexterous hovercraft leapfrogs all this, cutting the overall journey time in half.

For that reason, the Isle of Wight service outlived not just the cross-Channel hovercraft routes, but also those closer to home, such as Southampton to Cowes.

Its nimbleness even saves lives. In 2020, Hovertravel worked with the National Health Service, trialing trips for Covid patients to the mainland for hospital treatment. It worked so well, the hovercraft now doubles up as an amphibious ambulance for various medical emergencies.

In fact, used to convey everything from Amazon packages to vital organs, the hovercraft forms a vital high-speed link between the island and the rest of the country.

‘Like a Land Rover on ice’

Steve Attrill is Hovertravel’s head of marine operations. As a pilot he’s flown all manner of planes, and now as captain of a hovercraft his job description is… pilot. That’s because you don’t “sail” or “drive” a hovercraft; you “fly” it.

“It stems back to the pioneering days where the first operators of the hovercraft came from the aviation industry,” says Attrill, “My predecessors, the people who set the company up, were from a flying background. Our chief pilot when I joined back in 1988, he was an ex Vulcan bomber pilot.”

With just 10 hovercraft pilots on the route, the running joke is that they’re rarer than Top Gun crew members. Despite occasionally being mistaken for bus drivers, hovercraft pilots gain a degree of respect few other careers do. “There’s thousands of ships’ captains,” says Attrill, “There’s thousands of airline pilots. There’s not many hovercraft pilots.”

You need the steady hand of “Maverick” Mitchell to fly a hovercraft, too. “The machine is very much hands-on,” explains Attrill. “We don’t have an autopilot. It requires constant attention, which makes it an interesting craft to fly compared to either an aircraft or a ship.

“The craft is very maneuverable, but it will skid like a Land Rover on ice.”

Despite best efforts to ensure a smooth ride, the Solent can get choppy. A select group of thrillseekers prefer it that way, studying ahead for inclement weather then piling onto the next available Hovertravel service.

A second golden era?

Once the hovercraft had proved itself commercially viable in the 1960s, talk turned to how far Cockerell’s masterpiece might go.

“There was certainly an anticipation that a hovercraft would be the new form of transport that could see transatlantic travel changed,” says Steve Attrill. “They were expecting that one day it would replace ocean liners.”

Though not rakishly streamlined like Concorde, there was an air of glamor to these machines, which would whisk you to the continent in 35 minutes and serve you a drink en route. If there was a way to replicate that experience from the UK all the way to the USA’s East Coast, travel would never be the same again.

That dream, as we know, was sunk. Expenses aside, getting across the Atlantic in a hovercraft would involve unprecedented fuel capacity and the ability to stand up to some seriously egregious waves.

But could the hovercraft have a second stab at conquering short-haul travel?

“There’s a great future out there for it, and I hope it will see many other operators like ourselves worldwide,” says Attrill, who in 1998, headed up the team that established the first passenger hovercraft service in Canada.

“I strongly believe the hovercraft will continue to develop as technology moves on with new-generation materials, new-generation power plants.”

Alan Barkley agrees. “I’d like to see more money invested into the new electric hovercraft. There must be a way of getting these up and running and working,” he says.

Indeed, Saunders-Roe may be gone but another stalwart of the scene, Griffon Hoverwork – which created the current models used by Hovertravel – now manufactures the 995ED, a type of hybrid electric craft.

With environmental travel taken more seriously by the minute, and with cheerleaders like Griffon Hoverwork and Attrill, perhaps there’s a second installment in the saga of this eccentric yet ingenious invention.

Just don’t expect a new Dover-New York service anytime soon.