He’d only just arrived in Australia from Wales, but teenager Brian Robson quickly realized that he’d made a big mistake by emigrating to the other side of the world.

Unfortunately the homesick 19-year-old didn’t have the money to cover the cost of abandoning the assisted passage immigration scheme he’d traveled with in 1964, as well as his return flight home.

After realizing his options were pretty limited, Robson, from Cardiff, hatched a plan to smuggle himself onto a plane in a small box and travel back in the cargo hold.

Now, over 50 years after the extremely risky journey that saw his picture splashed across newspapers around the world, Robson is hoping to track down his old friends John and Paul – two Irishman who nailed down the crate and sent him on his way.

“The last I spoke to John and Paul was when one of them tapped the side of the box and said ‘You OK,’” he tells CNN Travel. “I said ‘yes’ and they said ‘Good luck.’ I’d love to see them again.”

Thinking inside the box

A year or so before he decided to mail himself home, Robson had been working as a bus conductor in Wales when he applied for a job on the Victorian Railways, the operator of much of the rail transport in Australia’s Victoria state at the time.

Shortly after his 19th birthday, he took a long plane ride across the world to start his new life in Melbourne, passing through Tehran, New Delhi, Singapore, Jakarta and Sydney.

“It was one hell of a journey,” Robson admits. “But it was better going than coming back.”

When he arrived in the Australian city, the Welshman discovered that the hostel he’d been allocated was “this rat infested hole.”

Although he hadn’t even started his job yet, Robson decided there and then that he didn’t want to stay in Australia.

“Once I’d made my mind up, nothing was going to change it,” he adds. “I was adamant I was coming back [home].”

He says he worked for the rail operator for around six or seven months before quitting both the job and the hostel.

Robson spent time traveling through the outback of Australia before returning to Melbourne and landing a job in a papermill.

However, he never adjusted to life down under and was still determined to leave. But there was the small matter of paying the Australian government back the fee for his flight over, and he’d also need to raise the cash for his flight home.

“It was about £700 to £800 (around $960 to $1,099),” he says. “But I was only earning about £30 ($41) a week, so it was impossible.”

Feeling frustrated, Robson decided to walk to the hostel that he’d originally stayed in to see if anything had changed. It was there that he met John and Paul, who had recently arrived in Australia.

The trio quickly became friends and went on to attend a trade exhibition where they spotted a stall for Pickfords, a UK-based moving company.

“The sign said, ‘We can move anything anywhere.’ And I said, ‘Maybe they could move us.’”

Although his remark was initially intended as a joke, Robson couldn’t get the thought out of his head.

The crate escape

The next day he visited the Melbourne office of Australian airline Qantas to find out the process for sending a box overseas, taking note of the maximum size and weight permitted, as well as the paperwork needed and whether the fee could be paid on delivery.

After gathering all of the information he needed, he went back to the hostel and told John and Paul that he’d found a way to solve his problem.

“They said, ‘Have you come into money or something?’” he explains. “I said, ‘No. I’ve found a way to do it. I’m gonna post myself. And Paul said, ‘Hang on a minute, I’ll go out and buy the stamps.’”

According to Robson, when he explained his plan fully, Paul “thought I was stupid,” but John “was a bit more easy going.”

“So we spent three days talking about it and eventually I had them both on my side,” he recounts.

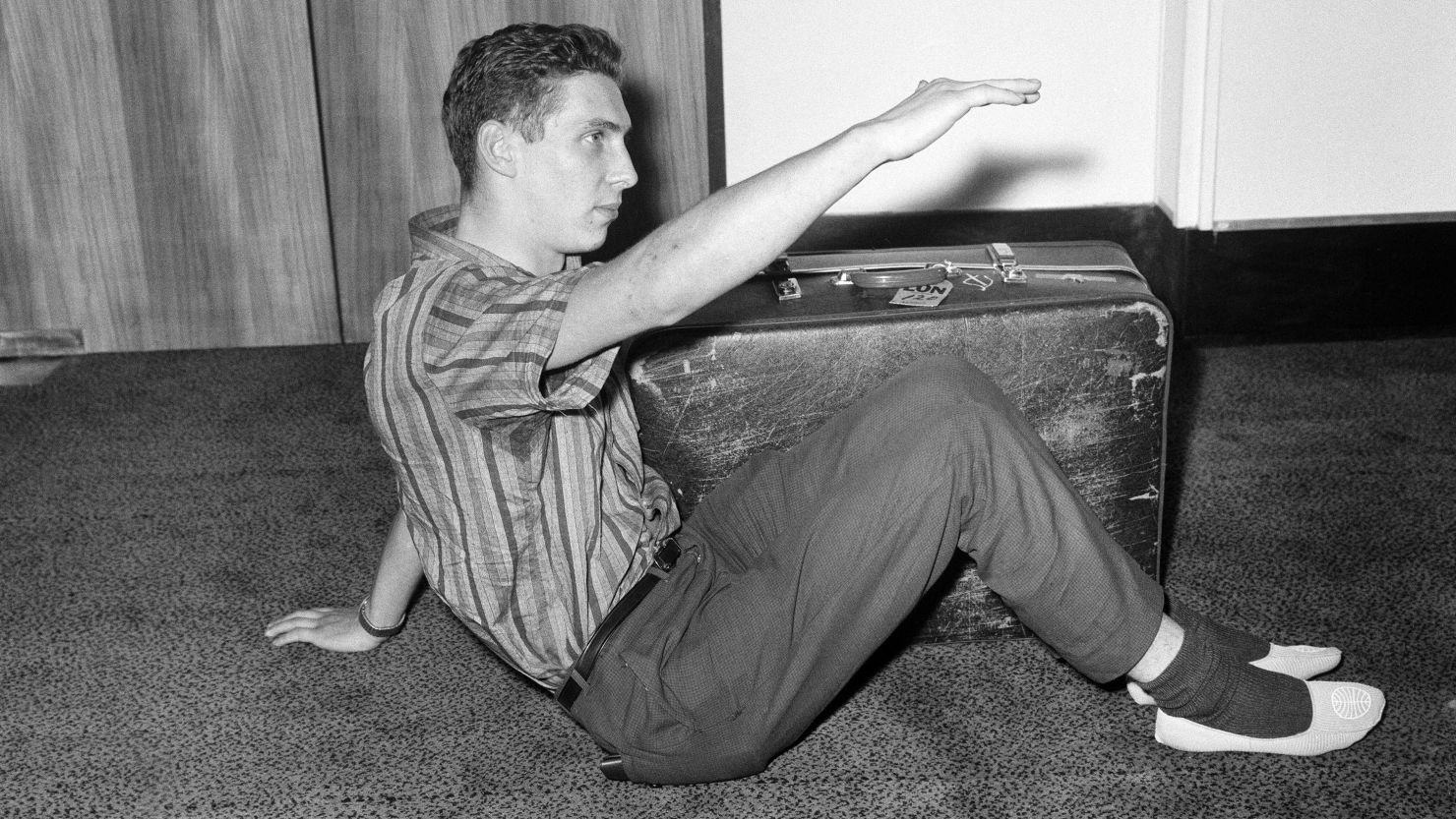

Robson then bought a wooden box measuring 30 x 26 x 38 inches and spent at least a month planning things out with his two friends.

They made sure there was enough room inside for both Robson and his suitcase, which he was determined to bring back with him.

He would also carry a pillow, a torch, a bottle for water, a bottle for urine, and a tiny hammer to force open the crate once he’d reached London, his intended destination.

The trio then completed a “trial run,” where Robson got inside the box and the others sealed it, and arranged for a truck to pick up the crate and take it to the nearby airport in Melbourne.

The following morning, Robson climbed into the wooden box once again, before John and Paul nailed it shut and bade him farewell. It would be another five days before he was freed.

“The first 10 minutes was fine,” he says. “But your knees start to cramp up when they’re stuck up to your chest.”

The crate was loaded onto a plane a couple of hours after he reached the airport.

“By then I was really cramping up,” he says. “The plane took off and it was only then I thought about oxygen. These planes were not pressurized, so there was very little oxygen in the hold.”

The first part of his journey was a 90-minute flight from Melbourne to Sydney, which was incredibly tortuous.

Tortuous journey

But Robson’s traumatic ordeal was about to get much worse. When the crate he’d squeezed himself into arrived in Sydney, it was put onto the tarmac upside down.

“So now I’m sitting on my neck and my head and I was there for 22 hours upside down,” he explains.

Although he’d booked the crate onto a Qantas plane to London, that flight was full, and it was moved onto a Pan Am flight to Los Angeles, which would be a longer journey.

“This flight took about five days,” he explains. “The pain was unbearable. I couldn’t breathe properly. I was drifting in and out of consciousness.”

Robson says he began having extremely vivid night terrors and couldn’t tell what was real and what was in his head.

“I thought they were going to throw me out of the plane,” he says. “I got into one hell of a state.”

He spent most of his time in the box in complete darkness and struggling to cope with the pain and confusion.

“At one point I thought I was dying,” he shares. “And I just thought ‘please let it happen quick.’”

When the aircraft reached its final destination, he resolved to go through with the rest of his plan.

“The idea was to wait until night time, knock the side of the crate out with the hammer I had on me and just walk home,” he says. “That’s how stupid the whole thing was.”

He was quickly discovered by two airport workers after dropping his torch onto the bottom of the crate.

Needless to say, the pair, who had spotted the beaming light coming from the box, were stunned when they took a closer look and saw a man inside.

“The poor guy must have had a heart attack,” says Robson, who only realized he was in America when he heard the workers’ accents.

“He kept screaming ‘there’s a body in there.’ I couldn’t answer him. I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move.”

The airport staff soon went to find their supervisor, but it was a while before they were able to convince anyone that it wasn’t a practical joke.

After confirming that the stowaway inside the crate was very much alive and no threat to anyone, the airport staff rushed Robson to hospital, where he spent at least six days recovering.

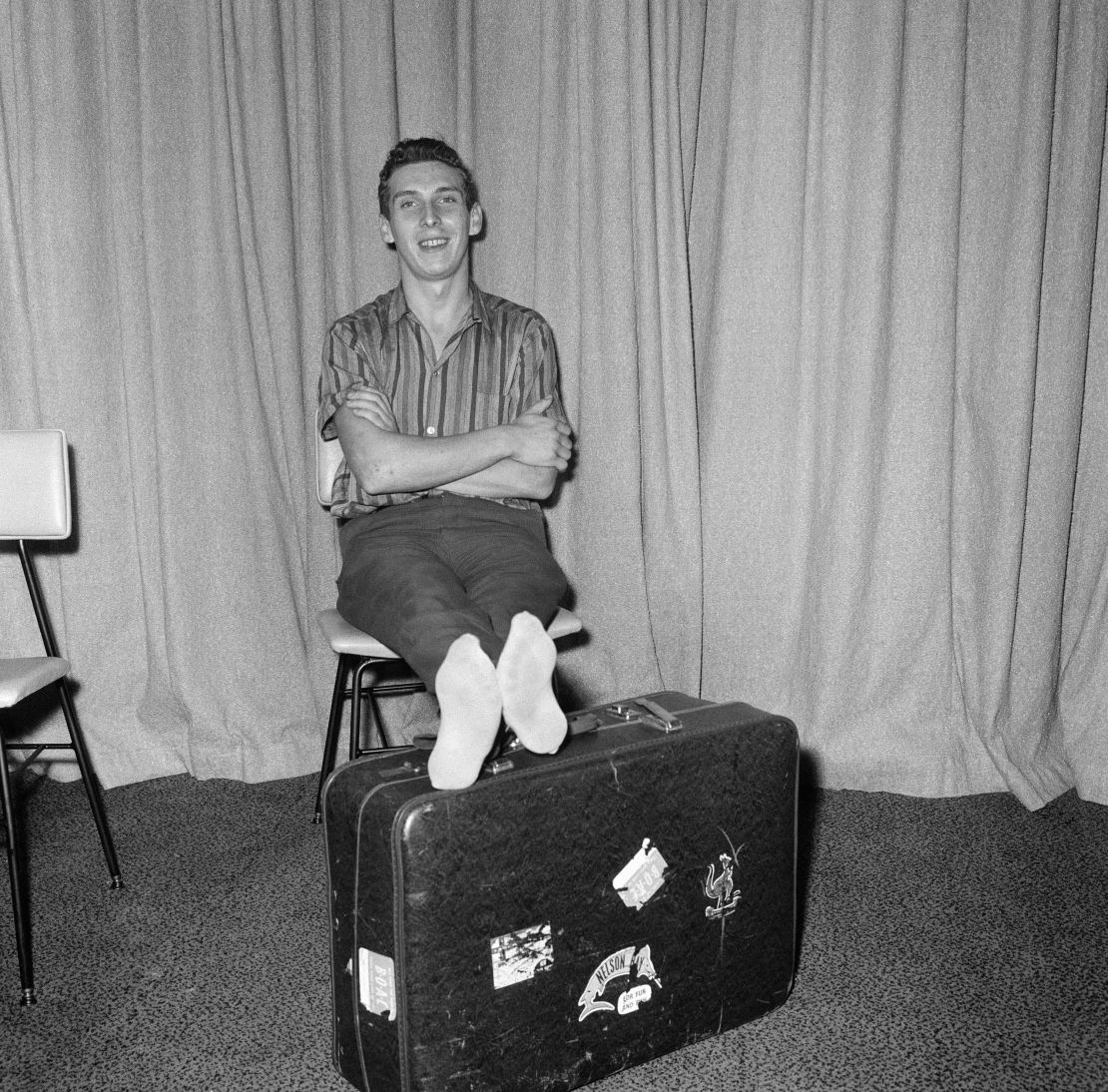

By that point his story had been picked up by the media, and reporters were flocking to hear the tale of the man in the crate.

Although Robson was technically in the United States illegally, no charges were filed against him.

The authorities simply passed him back to Pan Am, who arranged for the 19-year-old to fly back to London in a first class seat.

He was greeted by television cameras when he finally returned to the UK’s London Airport on May 18, 1965.

“My family were happy to see me, but they weren’t happy about what I’d done,” he admits.

Once he was back in Wales with his parents, Robson was keen to put the whole experience behind him.

Reunion hopes

But the publicity garnered by his now infamous journey meant he’d become a recognizable face, and the attention proved to be overwhelming.

Robson says he still feels haunted by the time he spent inside that crate and finds it difficult to talk about all these years later.

“It’s a part of my life that in all honesty I’d like to forget, but in all practicality I could never forget,” he says. “It’s just inbuilt in me.

“I mean, you try staying in a crate that long and see if you can forget it. I think it would have been easier in a coffin, because at least you could stretch your legs out.”

However, the incident has also brought a number of positive things to his life, Robson has written a soon-to-be-released book, “The Crate Escape,” which details the journey, and his story is also being developed into a movie.

Although he wrote to John and Paul soon after he returned to Wales in 1965, he isn’t sure whether they ever received the letters.

But he’s heard through the grapevine that they may have “done a runner” when his story first gained media attention.

It only recently occurred to Robson that his dear friends may have faced criminal charges if he had not survived the trip.

“I want to apologize for putting them in that position,” he says. “But in all fairness, it was a joint effort. They had some input into it. But I feel a bit guilty about it.”

While he won’t go into specific details, the 76-year-old says he’s received encouraging news regarding the pair in recent weeks and is hopeful that he may be close to finding them.

For Robson, reuniting with John and Paul would be a fitting way to round off the saga that he’s been unable to escape his whole life.

And while he’s lived in and traveled to various countries over the years, he’s never been back to Australia. However, there’s at least one circumstance that Robson would be willing to return for.

“The other day an Australian reporter asked me, would I consider going back,” he says. “I said, ‘Only if somebody pays my expenses and it’s for the reunion [with John and Paul]. Apart from that, no thanks.’”

“The Crate Escape” by Brian Robson is due to be released by Austin Macauley Publishers on April 30.