Editor’s Note: Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics. This story has been updated to reflect Theresa May’s statement. The opinions in this article belong to the author.

European political leaders are meeting in Brussels for a critical summit after a morale-boosting few weeks for the European Union.

After a lot tough talk from Britain over how it plans to leave the EU, the first official Brexit talks – which began this week – saw the UK’s chief negotiator strike a more conciliatory tone.

David Davis agreed that trade will only be discussed once the issues of how much money Britain owes the bloc and the rights of EU citizens living in the UK have been settled.

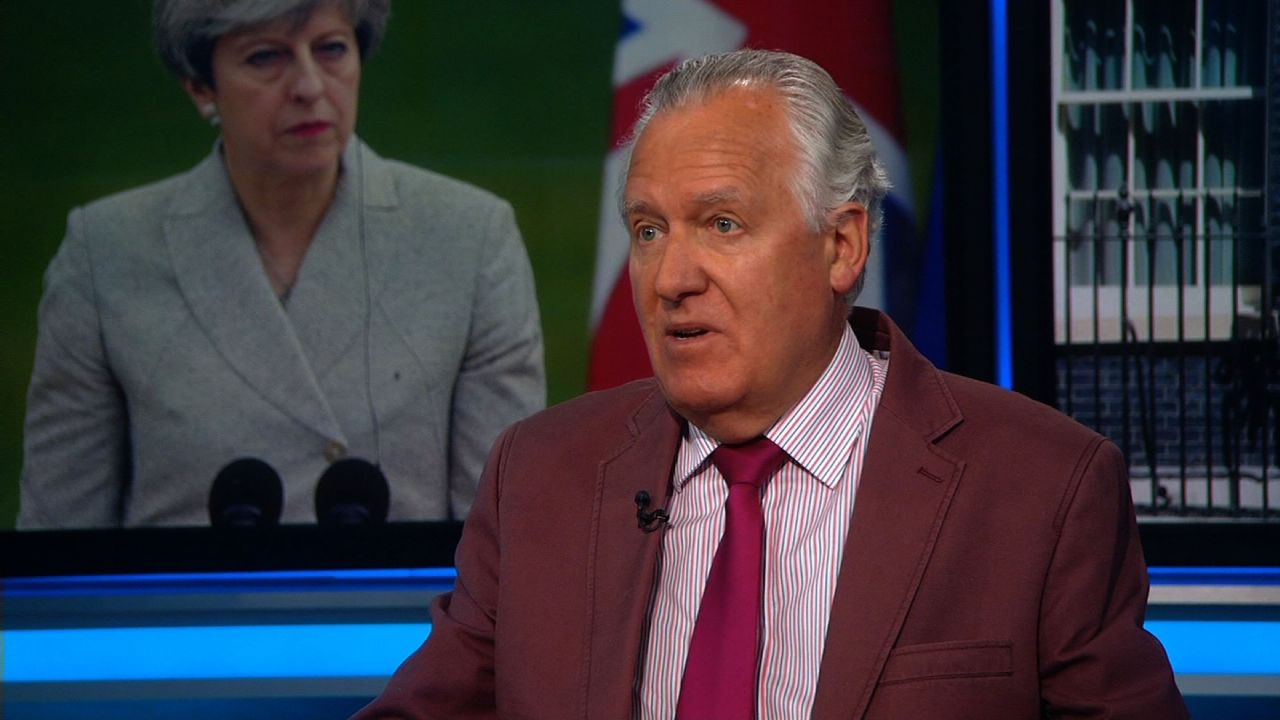

On cue, Theresa May confirmed on Thursday that none of the three million EU citizens currently living in the UK would have to leave once Britain leaves the bloc.

So, one year on from Britain’s decision to leave the EU, European leaders could be forgiven for feeling more optimistic about the continent’s future than they might have earlier this year, when Europhiles feared that Brexit and Trump’s victory in the US might fuel a spread of far-right populism and the prospect more member states considering their future within the union.

Following the failure of far-right populists to win in France and the Netherlands, Brussels senses that the current Euroskeptic wave may have reached its peak.

While only time will reveal if this is the case, the victories of liberal centrists in France and the Netherlands – plus the recent defeat of the far-right in Austria – is a significant turnaround in fortunes for those forces championing European unity and integration across the continent.

It was Macron’s victory that proved most decisive here, given the threat to the EU project had French National Front leader Marine Le Pen become France’s president.

This political fillip has been reinforced by stronger economic data, too. After several years of slow growth, the eurozone economies are now expanding faster than expected.

That these political and economic developments have, collectively, changed sentiment is shown by Italy’s Europe minister, Sandro Gozi. He remarked this month that we “now have a possibility of launching a new phase… We have to make the best of Brexit negotiations, we have to limit the damage… On the other hand, it is essential that there will be a parallel process of relaunch and deepening of European integration.”

The contrast here with the mood music of key European leaders from only a few months ago is striking. For instance, European Council President Donald Tusk said in January that the threats facing the European Union were then “more dangerous than ever.” He identified three key challenges “which have previously not occurred, at least not on such a scale” that the EU must tackle.

The first two dangers related to the rise of anti-EU, nationalist sentiment across the continent, plus the “state of mind of pro-European elites,” which Tusk then feared were too subservient to “populist arguments as well as doubting in the fundamental values if liberal democracy”.

At that stage, it was feared by some not only that Le Pen could pull off an upset victory, but also that the anti-establishment conservative Freedom Party, led by so-called “Dutch Trump” Geert Wilders, could win in the Netherlands.

While the salience of these two issues has subsided – though perhaps only temporarily – the third threat remains. That is what Tusk called the new geopolitical reality that has witnessed an increasingly assertive Russia and China and instability in the Middle East and Africa, which has driven the migration crisis impacting Europe’s politics. Intensifying this is uncertainty from Washington, which has publicly endorsed Brexit and attacked the European Union a number of times.

Nevertheless, numerous European leaders will believe that recent economic and political news has brought in at least a temporary respite and potentially a “window of opportunity” to move forward.

And at the summit, item one on the agenda will be how best to improve the internal and external security of Europe.

Here, there is growing consensus around what several European leaders have called a new, 21st-century European security pact, comprising measures to enhance security and border protection and greater EU intelligence cooperation to emphasize the resilience of the EU project.

Given the current disagreements within Europe on the wisdom of wider, grand integration initiatives – including in the economics and finance area – security issues are one of the few areas where there is significant consensus across the member states on the best way forward, post-Brexit.

Impetus for movement forward on this security agenda has been provided by recent terror attacks, the ongoing migration crisis, and the launch last year by high representative of the EU for foreign affairs and security policy, Federica Mogherini, of a new global strategy on foreign and security policy.

On a related theme, Brussels also now senses a potential window of opportunity to push forward a proposed European Defence Action Plan that advocates greater military cooperation between the EU member states.

Brexit could now also eliminate a longstanding obstacle to greater European cooperation in this area, given that successive UK governments have been opposed to deeper defense integration at the EU level.

European leaders might now sense that the Euroskeptic wave has passed its peak and that at least a temporary window of opportunity exists to move forward with a new EU integration agenda.

Decisions taken in coming months, including on the security front, will help define the longer-term political and economic character of the EU in the face of the continuing threats still facing the continent.