Story highlights

Pig organs are similar in size and function to human organs

Yet they can carry porcine endogenous retroviruses (or PERVs) so they can't be transplanted

Scientists say they used CRISPR to edit out these retroviruses in cells

Pigs may someday provide organs for human transplant surgeries, yet more than a few obstaclesmust be overcome first.

Using the genome-editing technology CRISPR, scientists deactivated a family of retroviruses within the pig genome overcoming a large hurdle in the path to the transplant of pig organs into humans.

Transplantation from one species to another – xenotransplantation – holds “great promise,” the American and Chinese research team believes.

“Porcine organs are considered favorable resources for xenotransplantation since they are similar to human organs in size and function, and can be bred in large numbers,” they wrote in a study published Thursday in the journal Science.

Retroviruses carry their genetic blueprint in the form of ribonucleic acid (or RNA) and transcribe this into deoxyribonucleic acid, commonly known as DNA. This is a reverse of the usual transcription process, which flows from DNA to RNA. This reversal makes it possible for retrovirus genes not only to infect cells but to become permanently incorporated into a cell’s genome.

In particular, the pig genome is known to carry porcine endogenous retroviruses (or PERVs), which are capable of transmitting diseases, including cancers, into humans. The presence of these PERVs means pig organs cannot now be safely transplanted into humans.

But George Church of MIT’s Broad Institute and Harvard, Dong Niu of Zhejiang University and their colleagues demonstrated a new method for deactivating the retroviruses in a pig cell line as a way to eliminate the transfer of PERVs to human cells.

First, the researchers proved that PERVs can be transmitted from pig to human cells and transmitted among human cells, even in conditions in which the fresh human cells have no prior exposure to pig cells.

Next, the team created a map of the PERVs in the genome of pig fibroblast (connective tissue) cells. Having identified a total of 25 PERVs, the science team used CRISPR to edit out – or deactivate – all those gene sites.

The scientists grew clone cells of these edited cells but were unable to cultivate one with greater than 90% of the PERVs deleted. But they added “ingredients” during the gene modification process – including both growth factors and growth inhibitors – and finally succeeded.

The new cells had 100% of the PERVs deactivated.

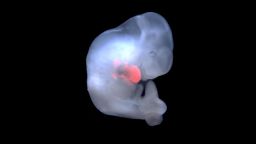

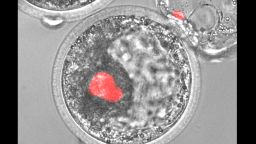

From here, the researchers produced PERV-inactivated embryos and implanted them into sows. The resulting piglets exhibited no signs of PERVs.

Dr. Ian McConnell, emeritus professor of veterinary science at the University of Cambridge, sees the research as a “promising first step.” McConnell, who was not involved in the study, added that “it remains to be seen whether these results can be translated into a fully safe strategy in organ transplantation.”

Formidable obstacles remain “in overcoming immunological rejection and physiological incompatibility of pig organs in humans,” he said.

In August 2016, the US National Institutes of Health announced that it was considering a revision to its policy, introduced in 2009, guiding human-animal chimera research. A chimera is a single organism containing cells (and DNA) from two or more organisms.

Scientists have been introducing human cells into animals to create models of diseases for decades, yet the 2009 policy suspended funding for chimera-based research due to ethical concerns.

With the advance of both stem cell and gene editing technologies, the ability to create more sophisticated animal-human chimeras raised concerns. Worries include human cells populating the brain of an animal thus humanizing that animal. Alternatively, human cells populating the germline of an animal could enable human genes to pass onto offspring.

The National Institutes of Health hopes a revised policy will enable research to continue – safely.

Join the conversation

The new research supports the value of using CRISPR to deactivate PERVs and so brings pig organs one step closer to safe transplantation, concluded the scientists.

Though more research is needed, they believe the “PERV-inactivated pig” can serve as a foundation strain that might be further engineered to “provide safe and effective organ and tissue resources” for transplantation into humans.