Adapted from “The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts” by Joan Biskupic. Copyright ? 2019. Available from Basic Books.

Chief Justice John Roberts has always had perfect timing.

Shortly before he reached high school age, an elite boarding school was founded near his northern Indiana home. Even as a young boy he knew that it offered a place to obtain a superior education and “stay ahead of the crowd,” as he wrote.

Roberts graduated from Harvard Law School as his brand of conservatism was in ascendance nationally. He joined the Reagan administration and with likeminded attorneys began trying to roll back liberal-era policies. “This is an exciting time,” he wrote to a mentor, ” … when so much that has been taken for granted for so long is being seriously reconsidered.”

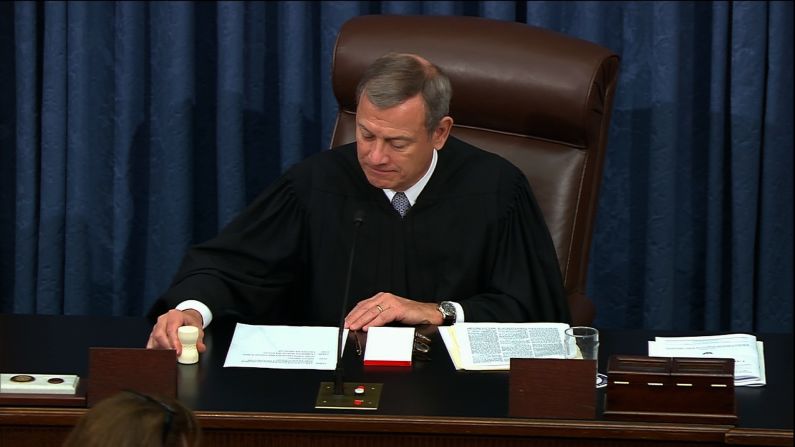

In 2005, when he was just 50, he was nominated to succeed retiring Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. But before confirmation hearings could be held, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died. A confluence of events – including public outrage over the administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina – prompted President George W. Bush to switch Roberts’ nomination to the Rehnquist vacancy in search of an easy political win.

Roberts became the youngest chief justice in more than 200 years, and from the start he has enjoyed a conservative majority on the nine-member bench.

The 2016 death of Justice Antonin Scalia and the possibility of a liberal appointment by then-President Barack Obama or a President Hillary Clinton might have deprived Roberts of that majority. But after the Senate stalled on Obama nominee Merrick Garland for nearly a year and Donald Trump became President, Roberts’ hand was, in fact, strengthened.

Trump appointees Neil Gorsuch, in 2017, and Brett Kavanaugh, in 2018, have put Roberts in charge of an even stronger five-justice conservative majority.

The law in America will come down to what Roberts says it is. The question is what this enigmatic figure who feels the weight of his position will do with his power.

Roberts, now 64, could remake the bench more in his conservative image, or he may opt to be more of an institutionalist, especially with Trump in office. He has already called out Trump for the President’s comments attacking judges.

RELATED: Supreme Court conservatives question challenges of partisan gerrymandering

Roberts also has signaled he may move cautiously. In February, he cast the fifth vote, siding with the four liberals, to block a restrictive Louisiana abortion regulation, at least temporarily. Roberts has long opposed abortion rights, but in this case, the disputed law was similar to a Texas regulation invalidated by the high court in 2016 (over a Roberts dissent), and it appeared a lower court was ignoring that ruling to uphold the Louisiana statute.

Roberts does not appear to be ready to break the pattern of his life’s work. He has staked out unflinchingly conservative positions in most areas of the law over the past 14 years. He wrote the Shelby County v. Holder decision that curtailed the reach of the Voting Rights Act and made it harder to prevent arguably discriminatory election procedures before they took effect.

Roberts also was part of the bare five-justice majority that produced Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, lifting limits on corporate and union money in elections, and District of Columbia v. Heller, which broke ground on the Second Amendment and declared an individual right to bear arms.

There is one major exception to his conservatism that has helped define Roberts in the public eye. In a 2012 dispute over the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, Roberts saved the Obama-sponsored health care overhaul from being struck down. That decision came only after the chief justice switched two key positions, angering conservatives and baffling liberals.

RELATED: Unlike Mueller, health care will likely be a top issue in 2020

It was seen by some as an assertion of independence. His declaration against Trump last November showed another kind of independence. Speaking on behalf of the entire third branch of government, Roberts reinforced his long-standing message that the judiciary is above the politics of other two branches.

“We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” Roberts said in a statement. It was a rebuke to Trump, who had criticized a judge who had ruled against the Trump administration as an “Obama judge.”

‘Sober puss’ to a ‘call to action’

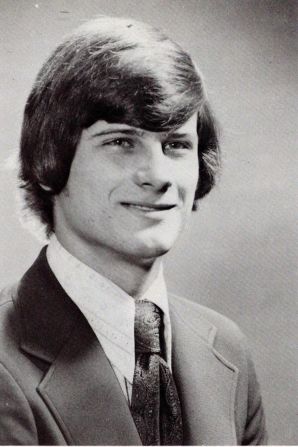

As a child, Roberts was so serious and focused that an aunt said he was sometimes known – fondly – as “sober puss.” He racked up A’s and became an academic star, shaped especially by La Lumiere, his all-male Catholic boarding school. Students took Latin all four years, along with calculus and other college-level work. Jacket and tie were required for class.

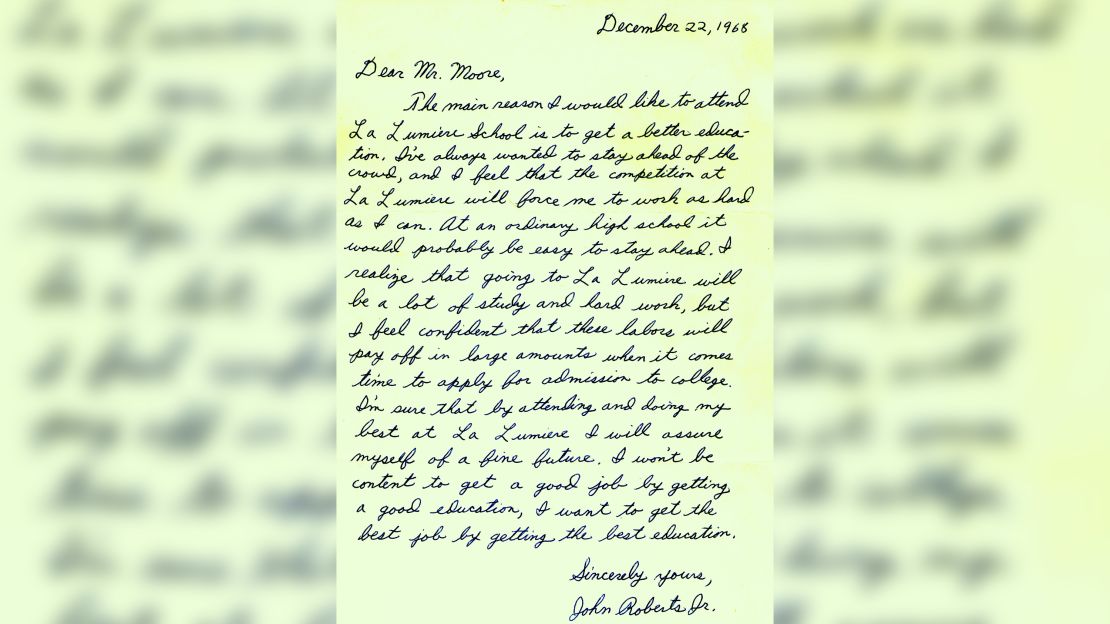

When Roberts applied to La Lumiere in December 1968 at age 13, he wrote to the headmaster in impeccable cursive: “I’ve always wanted to stay ahead of the crowd, and I feel that the competition at La Lumiere will force me to work as hard as I can. At an ordinary high school it would probably be easy to stay ahead. …. I won’t be content to get a good job by getting a good education, I want to get the best job by getting the best education.”

Once enrolled, a classmate recalled, “At 8 at night John would be studying. … at 8 in the morning John would be studying.”

RELATED: Where John Roberts is unlikely to compromise

Roberts graduated first in his class at La Lumiere and went to Harvard, where he majored in history. As he finished his studies in just three years, rather than the usual four, and went on to law school at Harvard, he was sometimes put off by the campus liberalism. But when he graduated in 1979, the country was on the cusp of a new conservatism.

Roberts later described hearing a “call to action” from Republican President Ronald Reagan. “I felt he was speaking directly to me.”

‘A gentle soul’

In the Reagan and then George H.W. Bush administrations, Roberts developed views that became the scaffolding for his positions on the bench today. Especially on affirmative action, voting rights and other racial issues, a straight line can be drawn from his legal work in the 1980s and early 1990s to the center chair of the Supreme Court.

Roberts was no mere follower of an agenda set by more senior administration officials. He embraced the conservatism of the day, was attuned to the administration’s messaging in the press and sometimes wrote memos complaining to bosses of colleagues on the legal team who were not all in.

Yet he was no firebrand in the public eye. Roberts, who carefully prepares for all appearances, has always sounded eminently reasonable, like the star advocate he was when he argued 39 cases before the high court. His confidence is manifest, but never brazen.

Roberts became an appeals court judge in 2003, appointed by President George W. Bush, and two years later, was chosen for the Supreme Court. Bush brushed away advisers who suggested he choose an older, more experienced nominee.

“Beyond the sparkling resume was a genuine man with a gentle soul,” Bush wrote in his 2010 memoir, “Decision Points,” of his impressions of Roberts. “He had a quick smile and spoke with a passion about the two young children he and his wife, Jane, had adopted. His command of the law was obvious, as was his character.”

One of the top aides whom Bush turned to for advice during the 2005 selection process was his staff secretary, Brett Kavanaugh. Bush said Kavanaugh suggested as a tiebreaker: “which man would be the most effective leader on the court – the most capable of convincing his colleagues through persuasion and strategic thinking.”

In late August 2005, as Roberts was preparing for his Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings, Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans. The storm surge overwhelmed the city’s levees and flooded many neighborhoods. The Bush administration bungled the federal response, delaying help for the region, where more than a thousand people died.

In the middle of the Katrina catastrophe, Chief Justice Rehnquist died, on September 3. Bush had no appetite for more controversy, and having seen senators’ initial glowing responses to Roberts, the President immediately moved the Roberts nomination to the Rehnquist seat.

RELATED: The inside story of how John Roberts negotiated to save Obamacare

The court’s reputation may depend on Roberts

From the beginning of his tenure, Roberts could count on four fellow conservatives for most of his positions. When Kennedy would shift to the liberal side, notably on social issues, Roberts often took a strong stand in opposition. The most conspicuous came in 2015, when he protested the majority’s decision that declared same-sex marriage a constitutional right.

For the first time ever, Roberts decided to read portions of his dissent from the courtroom bench. Justices take this dramatic step when they want to draw particular attention to their condemnation of a majority decision. In what is still Roberts’ only such oral dissent, he complained that the majority was infringing on an issue that should be handled by elected legislators.

“Just who do we think we are?” he asked rhetorically. “This is a court, not a legislature. … We have to say what the law is, not what it should be.”

Kennedy, who was the court’s voice on gay rights and its swing vote on abortion and affirmative action, retired last July after 30 years on the bench.

Roberts is now the member of the conservative bloc closest to the center. But he is unlikely to be a “swing vote” like Kennedy, whose flexible approach meant the four liberals could regularly attract his vote, especially on major social dilemmas.

RELATED: Chief Justice John Roberts sides with liberals in death penalty case

The reconstituted court will be tested in upcoming months on disputes already on its calendar involving religious rights and partisan gerrymandering, as well as petitions related to bias against gay men, lesbians and transgender people and related to abortion rights.

Already on the schedule for the new term that will begin in October is a major Second Amendment test involving a New York law that restricts the transportation of firearms outside of the home.

Roberts’ new control presents a new dilemma in his effort to make the court seem above politics. The five conservative justices were all appointed by Republican presidents; the four liberals by Democrats. And they do appear, depending on their presidential benefactors, to be “Bush judges” and “Trump judges,” or, alternatively, “Clinton judges” and “Obama judges.”

RELATED: Is Clarence Thomas headed out or just getting started?

The court’s reputation could depend on Roberts – and how he casts his vote and steers all nine.

In photos: Chief Justice John Roberts

Before he went to law school, he thought seriously about earning a Ph.D. in history at Harvard. He has remained a student of history.

“You wonder if you’re going to be John Marshall or you’re going to be Roger Taney,” Roberts said in 2010, referring to the chief justice revered as the forefather of judicial review and to the chief reviled as the author of the Dred Scott decision, which said slaves were not citizens, respectively.

“The answer is, of course, you are certainly not going to be John Marshall,” he said. “But you want to avoid the danger of being Roger Taney.”