Editor’s Note: Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

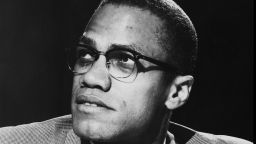

Malcolm X’s radical legacy continues to undergo an extraordinary resurgence in American politics and culture over half a century after his death, 56 years ago this week.

No less than Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X hovers over this national moment of reckoning around racial justice. His continued resonance in policy arenas related to ending mass incarceration, police brutality and the war on drugs is evident. So is Malcolm’s indefatigable pursuit of a human rights agenda broad enough to recognize the universality of Black pain and joy, oppression and resistance. Perhaps the least recognized aspect of Malcolm’s legacy that is finally coming to the fore is the personal.

The broad outlines of Malcolm X’s life have, by now, become the stuff of legend but are worth remembering. Malcolm Little’s trauma-filled childhood during the 1930s turned him into “Detroit Red,” whose active involvement in the criminal underworlds of Harlem and Boston during the 1940s led to a nearly seven-year jail stint in Massachusetts.

In prison Malcolm Little found his métier in religion and politics via membership in the Nation of Islam (NOI), unorthodox practitioners of Islam who believed in racial solidarity, economic self-determination, and that their leader Elijah Muhammad was the literal messenger of God. By the late 1950s, through a documentary hosted by Mike Wallace and reported by Black journalist Louis Lomax, Malcolm X and the NOI became household names whose calls for racial separatism and indictment against White racism lent a radical veneer to a group that eschewed formal political engagement.

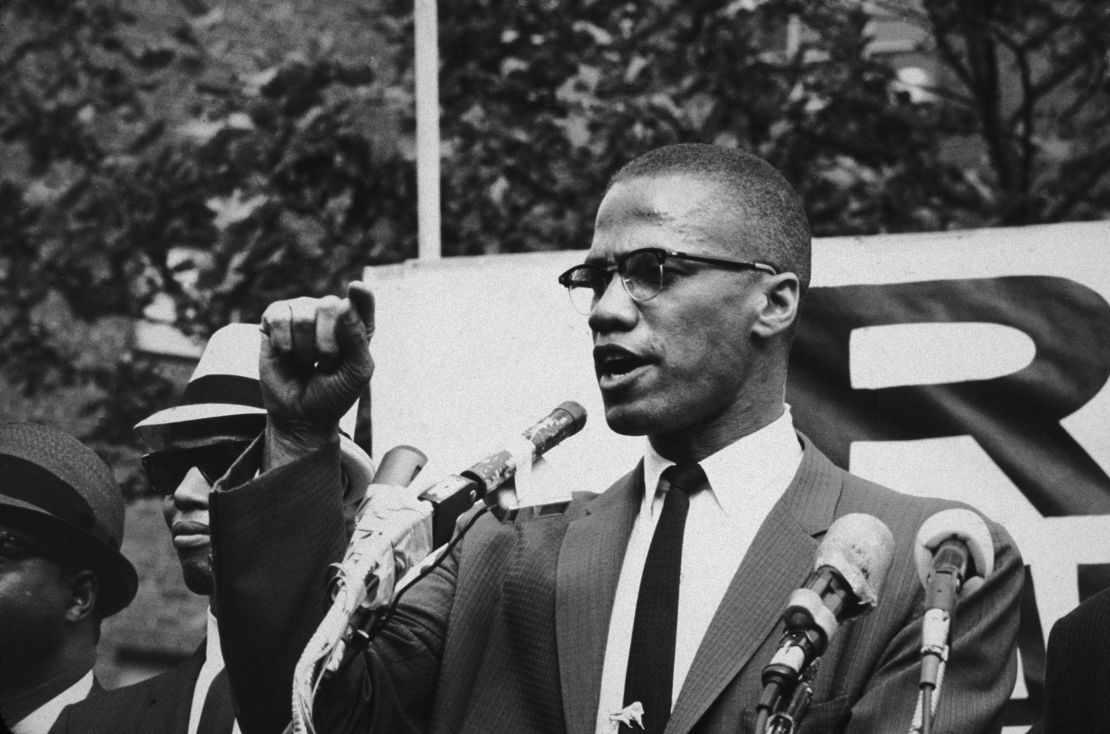

Malcolm X’s bold denunciation of White supremacy attracted thousands of new converts to the NOI, many drawn by his audacious display of Black intelligence, charismatic speaking style and ability to outclass a wide range of debate opponents. This included King, whom Malcolm derided as an Uncle Tom; Malcolm believed King’s nonviolent tactics invited further violence and humiliation on an already beleaguered race of people. Malcolm’s increasing fame and popularity attracted envy and criticism from his opponents and allies alike.

By the end of 1963, shortly after describing President John F. Kennedy’s brutal assassination as an example of “chickens coming home to roost,” Malcolm was suspended by the NOI. By the next year Malcolm started two new political organizations, took the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and enjoyed two extensive tours of Africa where he engaged in high-level diplomacy with heads of state and became Black America’s unofficial prime minister.

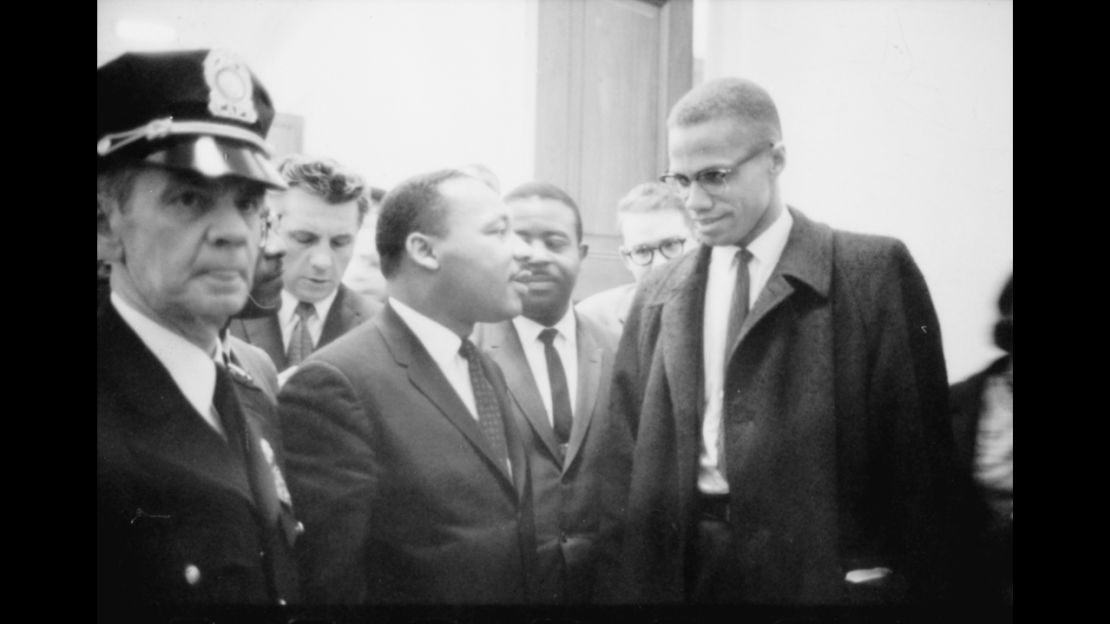

By the time of his February 21, 1965 assassination, Malcolm’s political evolution reflected a willingness to collaborate with former adversaries, most notably King, a recognition that politically progressive and sincere Whites could be part of a wider racial justice struggle, and an effort to convince the entire world that the struggle for Black dignity and freedom represented nothing less than a global human rights movement.

Bringing Malcolm X into new focus on the page

The tragedy of Malcolm’s death, as a spate of recent books, documentaries and movies make clear, is that the above sketch, while technically accurate, provides only a snapshot of a life that contained multitudes. “The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X,” the National Book Award-winning biography written by the late Pulitzer Prize-winning Black journalist Les Payne and his daughter, Tamara Payne, offers a kaleidoscopic, deeply researched examination of Malcolm’s early life.

The book’s title is a reference from one of Malcolm’s early letters to Elijah Muhammad regarding his successful efforts to recruit new NOI members in Hartford, Connecticut (where the young Les Payne first drew inspiration to write this book after hearing Malcolm speak). The “dead” were Black folks with no sense of their racial history, who instead continued to remain in the “grave” of a decadent White and Western society. This biography offers, through scores of interviews with surviving family members and Blacks and Whites who knew Malcolm, the fullest exploration of Malcolm’s early life.

In so doing, they discover that his father Earl Little, despite Malcolm’s recollection in his autobiography, died in a streetcar accident and not at the hands of White supremacists. Racism, however, still harassed the family from Omaha, Nebraska, to Lansing, Michigan, and the insurance company’s refusal to pay out Earl’s life insurance policy represented a form of structural violence Malcolm would spend his life fighting. The Little family were considered political mavericks who followed the teachings of the Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey, and Malcolm’s mother, Louise Norton, could have passed for White but was an indefatigable believer in Black pride.

“The Dead Are Arising” also documents, for the first time, the full scope of Malcolm’s juvenile delinquency – which included stealing from his own mother, acts of defiance that accelerated her emotional deterioration which resulted in a decadeslong stay in a psychiatric hospital. Like the recent six-part Netflix documentary “Who Killed Malcolm X?”, which resulted in New York reopening the investigation into Malcolm’s assassination, the Paynes assert that members of the NOI’s Muslim mosque that shot and killed Malcolm that day were never arrested.

Where the Paynes looked to recover the intimate familial experiences that shaped Malcolm X, recent film and television shows have tried to bring new shades to a screen portrayal that has been largely shaped by Denzel Washington’s Oscar-nominated performance in Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic. The actor Nigel Thatch brought a subtle and complex vision of Malcolm to the big screen in Ava DuVernay’s 2015 film “Selma” and, portraying the same character on a larger scale, in the 2019 10-part series, “The Godfather of Harlem.”

A more personal look at a legend

Kingsley Ben-Adir’s brilliantly passionate, despairingly vulnerable Malcolm X dominates Regina King’s magisterial recent film, “One Night in Miami.” Based on true events, the movie dramatizes (based on Kemp Powers’ screenplay) the night of February 25, 1964, following Cassius Clay’s upset victory over Sonny Liston to become heavyweight boxing champion of the world.

Malcolm, in limbo from the NOI but aware that forces within the group want to see him dead, is serving as mentor to the 22-year-old Clay, mere days away from being torn from his influence by Elijah Muhammad’s gift of the name Muhammad Ali. Soul singer Sam Cooke and NFL running back Jim Brown are also on hand for an evening that evolves into a discussion about racial justice, civil rights, democracy and the possibilities of a liberated future for four Black male icons, two of whom (Malcolm and Cooke) would be dead within the year.

“One Night in Miami” offers the best depiction of the humanity of Malcolm X. His passionate denunciation, swaggering charisma and sparkling intelligence are, as they should be, on display. But so is his biting sense of humor, active listening skills and aching vulnerability that occasionally led to bouts of despair. Malcolm’s unapologetic call for a political revolution capable of guaranteeing Black dignity and citizenship was, the film reminds us, rooted in personal sincerity, political integrity and an unabashed love for Black people, food, music and culture.

Malcolm X is still too often best remembered as the political sword who contrasted with Martin Luther King’s nonviolent shield. This facile, and historically inaccurate, juxtaposition is the subject of my recent dual biography, “The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.” Malcolm and King started off as adversaries who became rivals who, over time became each other’s alter egos.

King’s influence on Malcolm can be witnessed in the latter’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech which, for the first time, recognized the need for both dignity and citizenship in order to realize a racially just future. Likewise, Malcolm’s influence on King can be seen in the latter years of King’s career – increasingly sharp critiques of White supremacy, a warm embrace of Black pride and political self-determination and anti-war activism.

The unvarnished truth of Malcolm X’s life leaves us with the gift of discovering Blackness in all of its flawed humanity. Parts of the Black experience relegated to the lower frequencies of society are too often siloed, forced to become what outsiders identify them as being. Malcolm X was always more than the sum parts of the most brutal aspects of his personal and political experiences.

A dedicated father, loyal husband and man of faith, he was also an extreme lover of ice cream, deployed a wicked sense of humor and enjoyed photography and recording movies of his sojourns abroad. In that sense Malcolm’s profound legacy is not only in reminding us that Black lives matter, but that they can also reverberate with a purpose that continues long after death.