Supreme Court justices have long criticized each other’s legal reasoning, but they are increasingly impugning their colleagues’ motives and sincerity, in a way that matches the current political climate.

The Roberts Court, with three appointees of former President Donald Trump now in place, appears to be entering a new era of personal accusation and finger-pointing.

In the past, a single justice such as Antonin Scalia could be conspicuous for his short-fuse rhetoric, or a single controversy, for example, involving race, could stand out for provoking cross-charges. The current pattern may be a sign of deeper fractures on cases as the nine finish their annual term over the next month.

The trend belies the justices’ public assertions that they all get along and believe each operates in good faith. It’s not simply that they are swapping invective. As they speak of dealing in “good faith,” some appear to doubt it.

Liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor declared that a recent majority opinion authored by Justice Brett Kavanaugh was “fooling no one” with what she characterized as an “egregious” and “twist[ed]” interpretation of past relevant cases.

In a separate new case, liberal Justice Elena Kagan claimed Kavanaugh was engaging in judicial “scorekeeping” as he tried to turn one of her earlier opinions against her.

In that case, Kavanaugh protested he and other justices were acting in “good faith.”

In March, Justice Neil Gorsuch challenged his colleagues’ motives in a controversy that touched on today’s policing concerns and the Black Lives Matter movement. He said justices in the majority had brushed away court principles to side with a New Mexico woman shot by police while fleeing the scene, because of “new policing realities” and an “impulse” to offer some remedy in these times.

Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed Gorsuch’s suggestions, writing, “the dissent speculates that the real reason for today’s decision is an ‘impulse’ to provide relief … or maybe a desire ‘to make life easier for ourselves.’ … There is no call for such surmise.”

The pattern reveals more than internal squabbling. The public knows the court through its written opinions, and individual justices appear to be warning that some among them cannot be trusted to tell the truth or that they hold ulterior motives.

The recriminations mirror the discord in the two other branches of government, even as the justices protest that they are above it all.

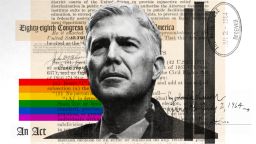

From Scalia to Gorsuch

Supreme Court history is peppered with episodes of personal antagonisms. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (who served 1902-1932) is said to have described the justices as “nine scorpions in a bottle.” Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962) and William O. Douglas (1939-1975) developed a well-documented, vicious antagonism.

Those eras have passed and in contemporary times the justices have spoken publicly about working well together. For the most part, they are a rhetorically restrained group.

Scalia, who served from 1986 to 2016, offered a notable exception. The year before his death, he mocked the four liberal justices who joined Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion, with its elevated tone, declaring a right to same-sex marriage.

“If, even as the price to be paid for a fifth vote, I ever joined an opinion for the Court that began: ‘The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,’ I would hide my head in a bag,” Scalia wrote.

Some current justices adhere to the Scalia method of legal interpretation, known as originalism, and his barbed style.

When the court ruled in March that Ford Motor Co. could be sued in states where victims of the vehicle injuries lived, Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, broke off with separate legal rationale and wrote at one point, “[I] t has become a tired trope to criticize any reference to the Constitution’s original meaning as (somehow) both radical and antiquated. Seeking to understand the Constitution’s original meaning is part of our job.”

He added: “What’s the majority’s real worry anyway – that corporations might lose special protections?”

Gorsuch has also suggested colleagues are seeking certain outcomes in a case, irrespective of the law. In an immigration controversy that broke the usual ideological lines, he wrote the majority opinion favoring an immigrant fighting deportation. He referred to dissenters’ view that the majority’s reading of the disputed statute would “impose substantial costs and burdens on the immigration system.”

“[T]hat kind of raw consequentialist calculation plays no role in our decision,” Gorsuch wrote.

Kagan to Kavanaugh: ‘Check, check, check’

A case this week, testing whether a 2020 decision forbidding non-unanimous jury verdicts was retroactive, produced the heated Kagan-Kavanaugh exchange about judicial “scorekeeping.”

But before Kagan got to that accusation, she made her case for why the court should have declared, based on court precedent, that the unanimity rule should be retroactive and available to defendants who had already exhausted their appeals.

“The majority argues … that the jury unanimity rule is not so fundamental because … . Well, no, scratch that. Actually, the majority doesn’t contest anything I’ve said about the foundations and functions of the unanimity requirement. Nor could the majority reasonably do so. For everything I’ve said about the unanimity rule comes straight out of” opinions written in the 2020 case, Ramos v. Louisiana.

“Just check the citations,” Kagan continued, “I’ve added barely a word to what those opinions (often with soaring rhetoric) proclaim. Start with history. The ancient foundations of the unanimous jury rule? Check. The inclusion of that rule in the Sixth Amendment’s original meaning? Check. Now go to function. The fundamental (or bedrock or central) role of the unanimous jury in the American system of criminal justice? Check. The way unanimity figures in ensuring fairness in criminal trials and protecting against wrongful guilty verdicts? Check. The link between those purposes and safeguarding the jury system from (past and present) racial prejudice? Check. In sum: As to every feature of the unanimity rule conceivably relevant to watershed status, Ramos has already given the answer—check, check, check – and today’s majority can say nothing to the contrary.”

Kagan then lashed out at Kavanaugh for asserting that Kagan lacked grounds to level some of her claims because she had dissented from the 2020 case. Kavanaugh wrote, “it is of course fair for a dissent to vigorously critique the Court’s analysis. But it is another thing altogether to dissent in Ramos and then to turn around and impugn today’s majority for supposedly shortchanging criminal defendants.”

Riled even more, Kagan suggested Kavanaugh considered cases in the aggregate, rather than individually, with an eye toward how opinions would be seen overall.

“No one gets to bank capital for future cases; no one’s past decisions insulate them from criticism,” wrote Kagan. “The focus always is, or should be, getting the case before us right.”

Kavanaugh responded that Kagan’s assertion was “misdirected” and that he and others had “acted in good faith in deciding the difficult questions before us.”

When Kavanaugh prompted Sotomayor’s retort in an April case that he and fellow conservatives in the majority were “fooling no one,” the controversy involved juvenile defendants, and Kavanaugh tried to downplay their differences.

The majority had ruled that precedent permitted juvenile offenders to be sentenced to life without parole even if no determination had been made that the juvenile was irreparably corrupt.

Sotomayor said that conclusion “would come as a shock” to the justices who crafted earlier relevant cases and who regarded “a lifetime in prison [to be] a disproportionate sentence for all but the rarest children, those whose crimes reflect ‘irreparable corruption.’”

Insisted Kavanaugh: “We simply have a good-faith disagreement with the dissent over how to interpret (past cases). That kind of debate over how to interpret relevant precedents is commonplace.”

The chief justice joins the fray

Fellow conservatives Roberts and Gorsuch collided in a separate, earlier instance this session when Gorsuch said the chief justice had wrongly justified Covid-19 restrictions by reaching back to a 1905 decision, Jacobson v. Massachusetts, that involved a smallpox outbreak. “Jacobson hardly supports cutting the Constitution loose during a pandemic,” Gorsuch said in the November controversy.

Roberts said Gorsuch was exaggerating his prior use of the ancient case, which prompted Gorsuch to further criticize the chief justice. Roberts then rejoined that while he had given Jacobson “exactly one sentence” in a prior case, Gorsuch’s criticism of Roberts’ use of it “occupies three pages.”

The chief justice has demonstrated in the past that even as he answers a detractor, he believes the give-and-take can undermine the court’s reputation.

In 2014, he and Sotomayor engaged in a memorable and cutting exchange over the value of government racial remedies. Sotomayor cited colleagues’ “refusal to accept the stark reality that race matters” and turned a familiar phrase of Roberts against him.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race,” she said, “is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

RELATED: Where John Roberts is unlikely to compromise

Roberts responded, “To disagree with the dissent’s views on the costs and benefits of racial preferences is not to ‘wish away, rather than confront’ racial inequality. People can disagree in good faith on this issue.”

But he insisted, “it similarly does more harm than good to question the openness and candor of those on either side of the debate.”