Editor’s Note: David A. Andelman, a contributor to CNN, twice winner of the Deadline Club Award, is a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor, author of “A Red Line in the Sand: Diplomacy, Strategy, and the History of Wars That Might Still Happen” and blogs at Andelman Unleashed. He formerly was a correspondent for The New York Times and CBS News in Europe and Asia. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

In so many ways, the world we know today would not be the same without Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the former Soviet Union who died at the age of 91 on Tuesday.

It is not impossible to think that communism might still reign in the eastern half of Europe. The Soviet Union might have been held together as a single, deeply troubled, increasingly impoverished nation, rather than today’s 15 more-or-less sovereign states. The Kremlin could quite possibly still be locked in an increasingly dangerous nuclear arms race with Washington.

But Gorbachev set the stage for a dramatic change of direction for the two superpowers of the day, one that might never have taken place without so many elements of his rich and textured life converging during his six years in power. There would likely be no independent nation of Ukraine – or, for that matter, there would not be so manymembers of the NATO alliance today.

There is so much more that might have changed, perhaps for the better, doubtless for the worse, had Gorbachev never propelled himself into the leadership role. Little of this was what he set out to accomplish when he took power in the Soviet Union as general secretary of the Communist Party in March 1985.

There remains a question – whether without Gorbachev and the manifold reforms he launched in the increasingly sclerotic Soviet system and the military and security apparatus that underpinned it, the USSR could have survived longer.

At a private dinner before US President Ronald Reagan’s first inauguration in 1981, his chief Soviet adviser, the late Harvard historian Richard Pipes, confided in me that by the end of Reagan’s years, the Soviet Union would cease to exist. America would have spent them to death. That was the goal he said he shared with Reagan. Effectively, Gorbachev had no choice but to play into this hand.

Gorbachev was at once a product of the system he eventually tried to dismantle or at least reform dramatically. He was also a realistic observer of its vast and pernicious failings. “The slightest deviation from the established course was nipped in the bud,” he would write later. “Should you come up with your own ideas – be prepared for trouble. You could even land in jail.”

But he also recognized what it took to succeed. He needed friends and mentors in high places. One of these was Yuri Andropov, former head of the KGB, who took over as the Soviet leader when Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982. There were many who believed Andropov held the key to breaking up the bloated and corrupt apparatus that had led the Soviet Union since Joseph Stalin and that he would lead the USSR to become a viable competitor with its arch foe, the United States.

Andropov died suddenly in 1984 after just 15 months in office. Gorbachev waited in the wings as Konstantin Chernenko, a Brezhnev clone and Andropov’s successor, was anointed the new leader. But Chernenko lasted only months. In March 1985, after Chernenko died of a heart ailment and emphysema, it was Gorbachev’s turn.

And it was not an easy debut. Oil prices, the backbone of the Soviet economy, were collapsing. Eventually, Gorbachev contemplated turning the nation into a capitalist market and economy, but recognized the futility of that idea. He did fully embrace the twin notions of “glasnost” or maximum openness, twinned with “perestroika” or restructuring. To these ends, he embarked in his earliest years in power on a host of reforms – attacking corruption at all levels of the Communist Party, authorizing multi-party elections in Soviet cities, lifting restrictions on the media.

But he did recognize one reality. What was really bleeding the Soviet Union dry was the arms race. He had to find some way to put a stop to that.

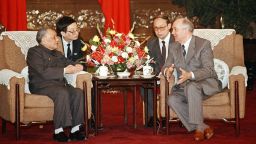

This was the grim reality Gorbachev faced when he proposed a make-or-break summit with President Reagan, then headed to Reykjavik, Iceland, in October 1986 for two long, fraught days of talks. It was the first time I’d ever seen Gorbachev in action. It was a masterful performance. Here clearly was a man of force, vision, great power and endurance.

But he left the American side utterly bewildered. What they had not seen coming was Gorbachev’s surprise proposal to end the nuclear arms race and dismantle the entire nuclear arsenals of both sides – zero nukes under one critical condition: Reagan would have to agree to halt any development outside a laboratory or deployment of his Star Wars anti-missile system that had been so close to the American president’s heart. Gorbachev recognized that the Soviet Union could never hope to match this system without a catastrophic level of expenditures that would utterly destroy the Soviet economy. Reagan refused.

The summit broke up in disarray. Gorbachev returned home in apparent defeat. But not entirely. Eventually, the spirit of Reykjavik led to other, more modest agreements – an end to nuclear-armed intermediate-range rockets in Europe in 1987, followed a year later by a large-scale pullback of conventional troops from Europe. Further agreements and cutbacks followed in the same spirit, to the extent that the size of the two nation’s nuclear arsenals would shrink from some 72,000 at their peak when the two leaders met in Reykjavik to barely 13,000 today.

“Subsequent events confirmed my judgment,” Gorbachev wrote in 2019, in a preface to the book by Guillaume Serina that I translated, “An Impossible Dream: Reagan, Gorbachev, and a World Without the Bomb.” Then he added, “We have had great successes. The Cold War was relegated to the past. The danger of global nuclear conflict is no longer imminent.”

Back home, Gorbachev set to work dismantling the system that had proved so dysfunctional in its first seven decades, clearly unable to meet the challenges of the modern world. He completed the withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 and told east European leaders they were effectively on their own.

By 1989 the nations of eastern Europe had severed their ties with the Kremlin and the process began with the republics of the Soviet Union. Reagan’s 1987 challenge to Gorbachev to “tear down this Wall,” had come to fruition.

While Gorbachev continued to express a belief in communism and its political party as a progressive force, after briefly surviving a failed coup attempt in August 1991 he was finally forced to resign in December of that year in favor of a febrile and alcoholic Boris Yeltsin. The Soviet Union collapsed a day later.

Gorbachev concluded the preface he wrote for our book with what might effectively be his epitaph: “What we need today is precisely this: political will. We need another level of leadership, collective leadership, of course. I want to be remembered as an optimist. Let us assimilate the lessons of the 20th century in order to rid the world of this legacy in the 21st – the legacy of militarism, violence against the peoples and nature, and weapons of mass destruction of all types.”

But one big question remains. Had Gorbachev not been in place to undertake his reforms, setting the Soviet Union on the path toward a dismantled Russian empire, would the way have been clear for a Vladimir Putin to arrive with his own even more toxic vision? As the war in Ukraine grinds on, it’s a question that hangs in the air.