The Supreme Court gathered Wednesday to consider a case that could change the future of federal elections – a 3-hour session that might never have occurred if it wasn’t for former President Donald Trump.

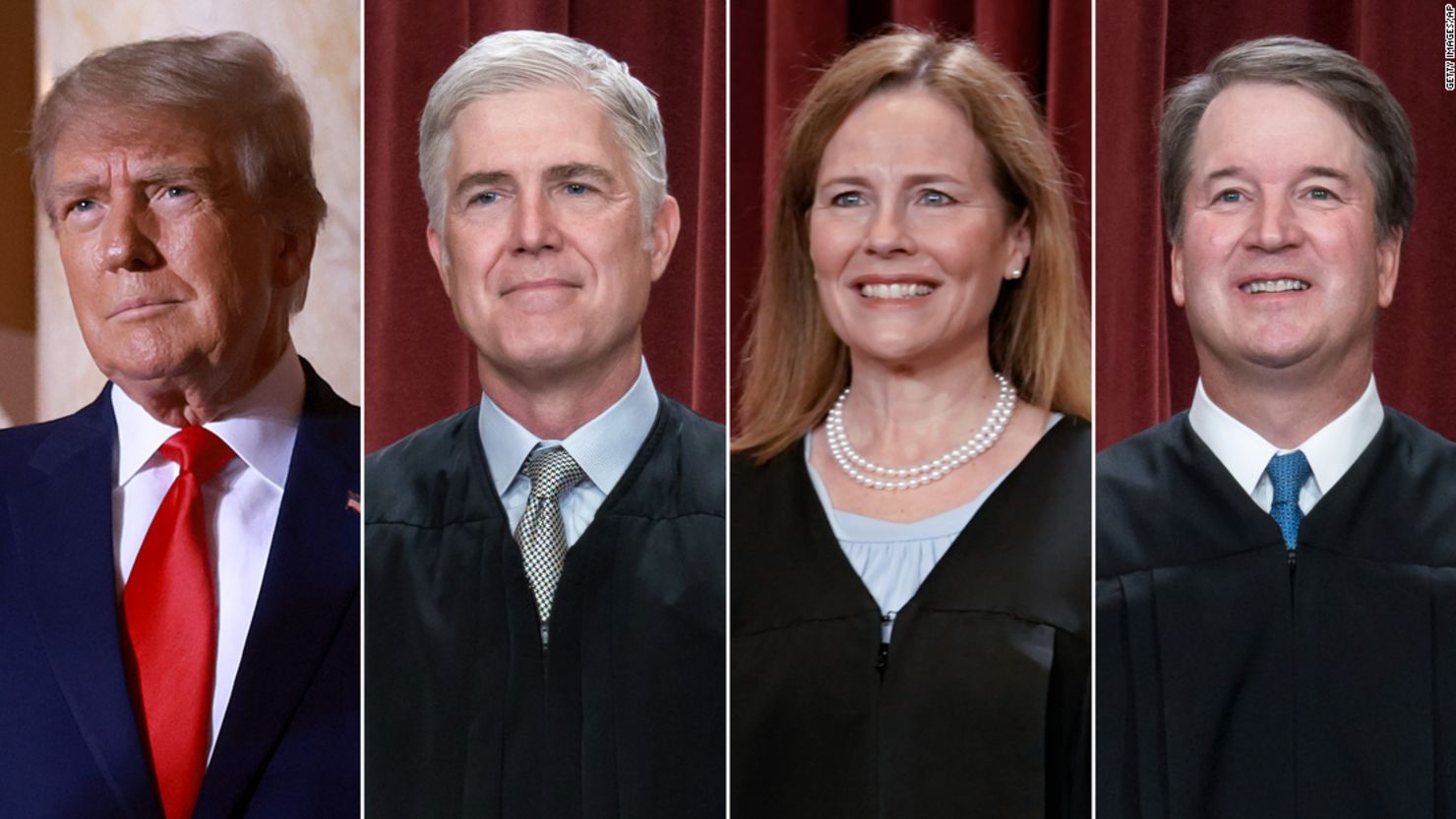

The dispute is another reminder of the impact that Trump has had on the current court. Not only did he place three appointees on the bench – ensuring conservative wins in areas such as religious liberty, the Second Amendment and abortion rights, and brought numerous cases fighting subpoenas for tax returns and other documents to the court, but his supporters helped to revive the long-dormant legal theory that was central to Wednesday’s case as they sought to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

The so-called Independent State Legislature doctrine – a theory that says state legislatures can’t be constrained by state courts on voting rules when it comes to federal elections – could upend electoral politics going forward and embolden state legislatures to act without judicial oversight, Democrats and some conservatives argue.

It’s been mostly ignored for 20 years, yet as the justices brought up repeatedly during oral arguments Wednesday, a version of it was employed by then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist back in 2000 amidst the legal challenges between George W. Bush and Al Gore over the presidency.

As supporters of Trump battled in voting rights challenges in 2020, versions of the doctrine re-emerged.

“People had made a version of the independent state legislature argument, but it didn’t get any purchase until the 2020 election when it emerged as potentially decisive in certain swing states like Pennsylvania,” said Carolyn Shapiro, a professor of law at Chicago-Kent College of Law, who is an expert on the issue.

And while the justices prepared for oral arguments in the case at hand, the theory was noted in eight cases during the midterm elections, according to Democratic election lawyer Marc Elias.

But it’s more difficult to call a theory “fringe” when at least four Supreme Court justices urged their colleagues to take up the case.

Jason Snead, a conservative who runs the Honest Elections Project, said that during the leadup to the 2020 election there was extensive litigation in battleground states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, where, Snead contends, Democrats were “asking courts to re-write election laws.”

“Any Republican presidential candidate or their lawyer would have raised arguments around the Elections clause to defend the laws on the books in these states” Snead said.

Trump zeroed in on the Supreme Court while first running for president, vowing to change the face of the bench. Working with then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, and then-Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley, he focused on judicial nominees who considered themselves “originalists” in the mold of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Originalists say that the Constitution should be interpreted based on its original public understanding.

His first nominee, Neil Gorsuch, was particularly aggressive Wednesday suggesting that the lawmakers’ arguments were rooted in such historical tradition.

Gorsuch is already on the record with Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas in support of the lawmakers and their version of the so-called Independent State Legislative doctrine in an order released at an earlier phase of the case. Back then, they called the issue an “exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law.”

It may be Trump’s other two Supreme Court nominees, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, who decide how the court eventually rules.

At oral arguments, Kavanaugh and Barrett did seem to question the more sweeping nature of the arguments put forward by an attorney for the lawmakers. But they also appeared prepared to side at least in some limited way with the lawmakers – although a lot can change after oral arguments when the justices have to actually craft a consensus opinion.

Voting rights experts are very leery about a so called “narrow opinion” from the court that could come from such a middle ground position. That’s because they fear that even an incremental win for the North Carolina Republican lawmakers in the case at hand will trigger more challenges down the road.

Take, for instance, a friend of the court brief filed by John Eastman, the lawyer who served as a key architect of the push to overturn election results for Trump. The case at hand would not give the legislature the power to ignore a popular election for president and choose its own slate of electors, but it could inspire such lawsuits in the future.

“Such a win could also let legislatures change the rules before an election so that they are the ones instead of the courts that are resolving disputed election results,” said Shapiro.

To be sure, since he left office, Trump has not fared so well at the Supreme Court despite the volume of cases he’s asked the justices to review. Most recently, the justices cleared the way for the release of his tax returns to a Democratic-led congressional committee.

But his impact on the high court – changing the institution and the law going forward –will continue to be immense for years to come.