Editor’s Note: Jim Bendat is the author of “Democracy’s Big Day: The Inauguration of Our President, 1789-2013.” Steve Lubet is the Williams Memorial Professor at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. The opinions expressed in this commentary are theirs.

Story highlights

Democratic candidate in 1968 was defeated in part due to opposition from anti-war members of his own party

Jim Bendat and Steve Lubet say they learned that refusing to vote for the lesser of evils candidate was a horrible mistake, with tragic consequences

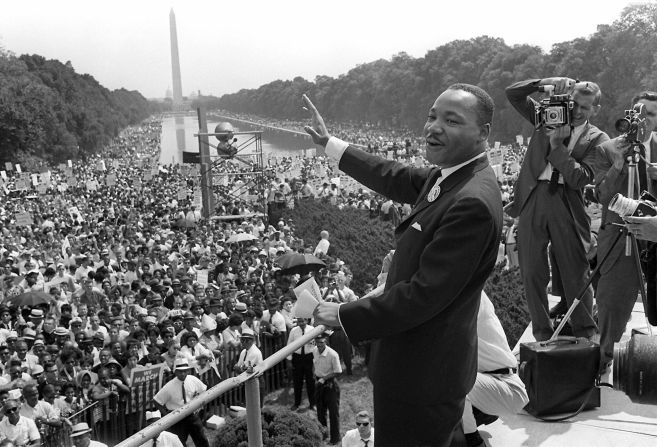

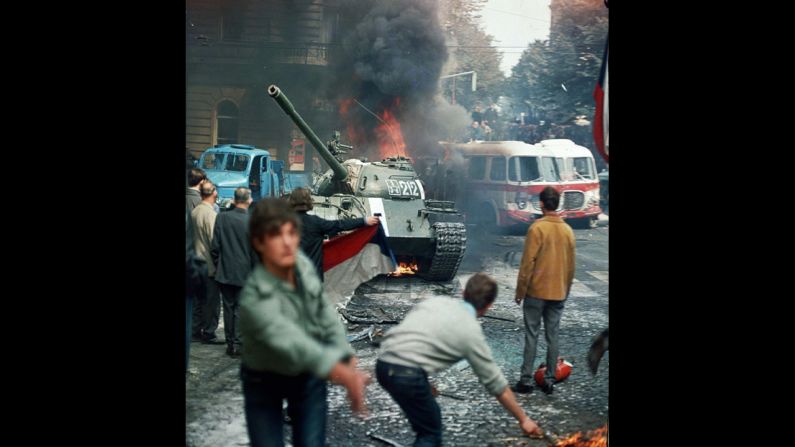

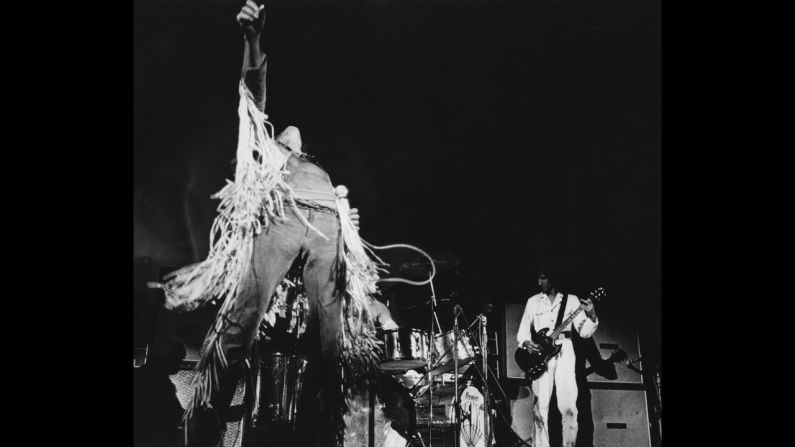

On a warm August night in 1968, the two of us joined thousands of other young people in front of Chicago’s Hilton Hotel, braving tear gas and billy clubs to demand an end to the Vietnam War. While delegates to the Democratic Convention remained sheltered inside, with police and National Guard troops protecting the entrances, we shouted “Bring the Troops Home” and “The Whole World is Watching.”

We didn’t realize it at the time, but our most consequential chant was “Dump the Hump,” derisively aimed at Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had until then refused to distance himself from the war policies of President Lyndon Johnson. We wanted to change how the government worked – and it turned out that we did, although far from the way that we wanted.

The Democrats had been fighting among themselves throughout 1968. President Johnson had been poised to run for another term, but Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota announced in late 1967 that he would challenge Johnson on an anti-war platform. Many college students took up McCarthy’s cause, and the challenger nearly won the first primary, in New Hampshire on March 12.

Four days later Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York, sensing that Johnson was vulnerable, decided to run. Then, suddenly, on March 31, Johnson announced that he was withdrawing from the race. There was little secret to Johnson’s motivation: by dropping out, he would avoid the embarrassment of losing his party’s nomination, and he could join party bosses such as Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley in support of Vice President Humphrey.

Humphrey didn’t officially announce his candidacy until April 27, conveniently too late to enter any of the nation’s fourteen primaries. (Delegates from the other 36 states were chosen in party conventions that were typically dominated by local political bosses.) Consequently, the big primary elections that spring – most notably, Indiana, Oregon and California – were contests between McCarthy and Kennedy. Then came Kennedy’s assassination, on the same night as the California primary, leaving McCarthy as the only anti-war challenger to Humphrey.

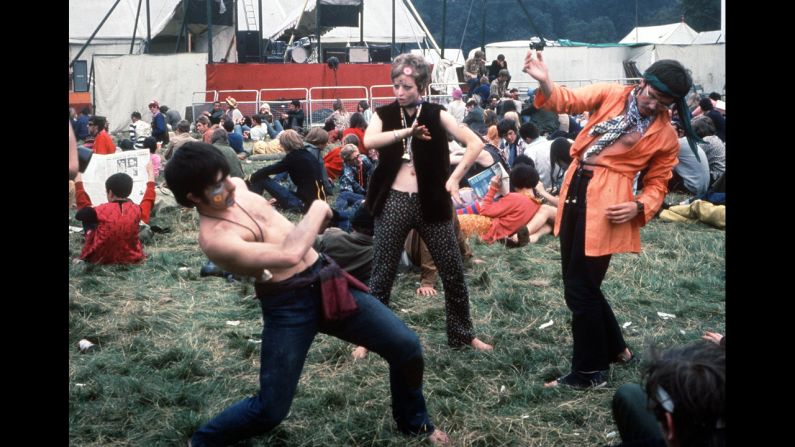

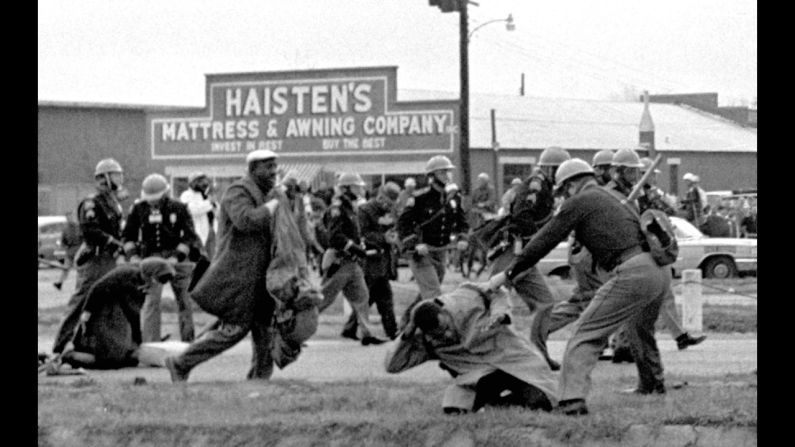

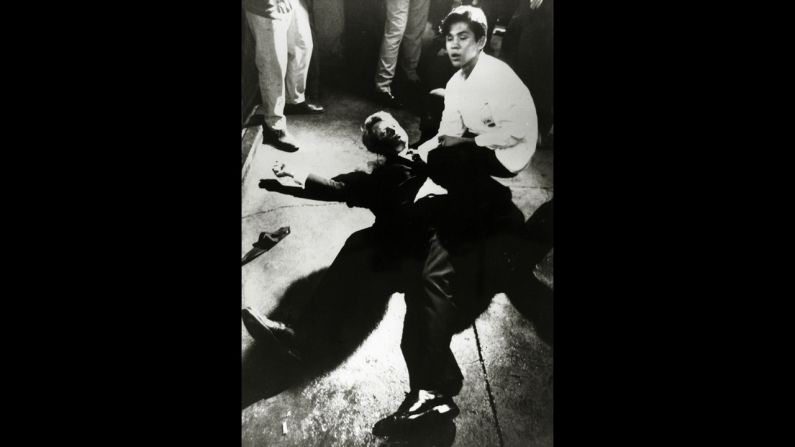

That August, the Democratic National Convention took place in Chicago. Humphrey, despite having won zero primaries, easily won the nomination, which seemed as though it had been rigged from the beginning. Young people, and some who were not so young, flooded the streets and parks in protest. The cops responded by cracking heads, in what Connecticut Sen. Abraham Ribicoff called “Gestapo tactics.”

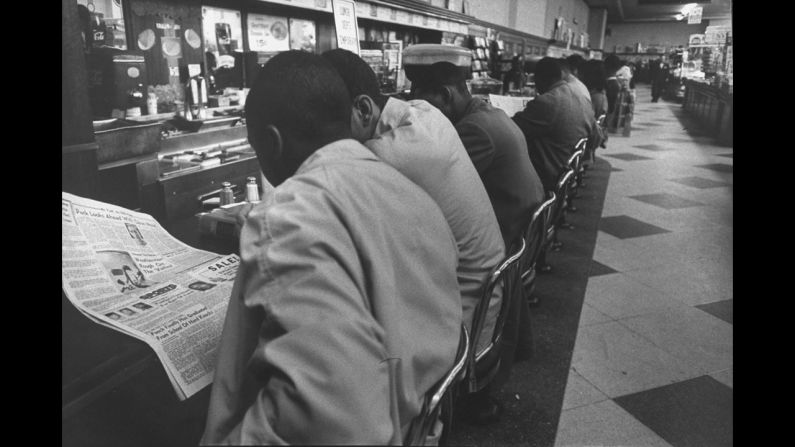

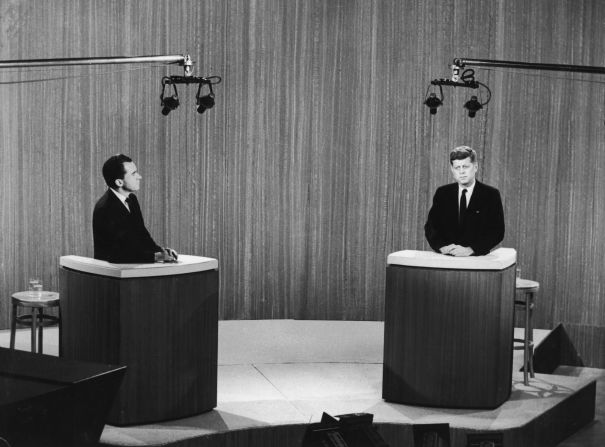

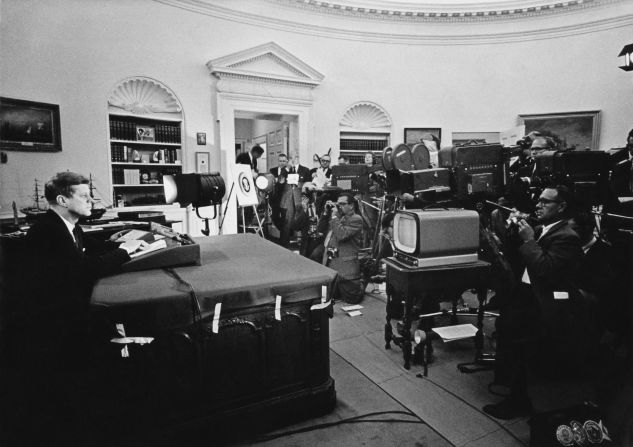

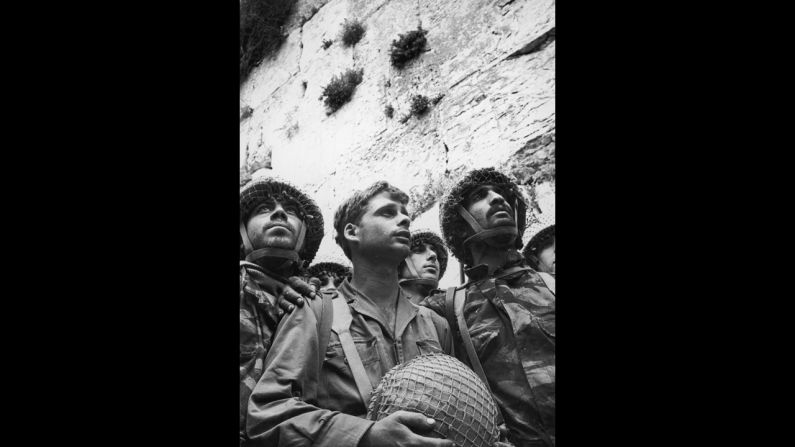

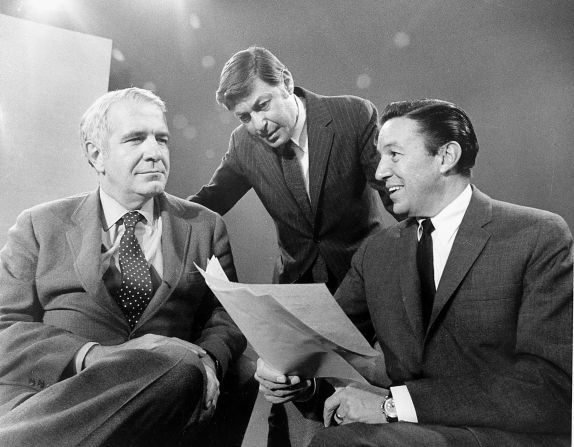

When Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey squared off in the 1968 election, along with third party candidate George Wallace, the biggest issues were the Vietnam War, civil rights, and anticipated vacancies on the U.S. Supreme Court.

As undergrads at Northwestern, neither of us could yet vote in1968 (the voting age was still 21 at the time) but it would not have mattered. Many thousands of Democrats had been alienated by the “police riot” at the Chicago convention, and they stayed away from the polls out of “principle.” The two of us surely would have done the same.

To us, Humphrey, Nixon and Wallace were all pro-war, with no meaningful difference between them. Humphrey’s leadership in the civil rights movement seemed like ancient history, and his association with LBJ was more than enough to condemn him in our eyes. We wanted to change the world, and we thought we had a lot of answers – none of which involved picking the lesser of evil candidates.

We were immature and shortsighted in 1968, rejecting Humphrey even when he belatedly announced his opposition to the war.

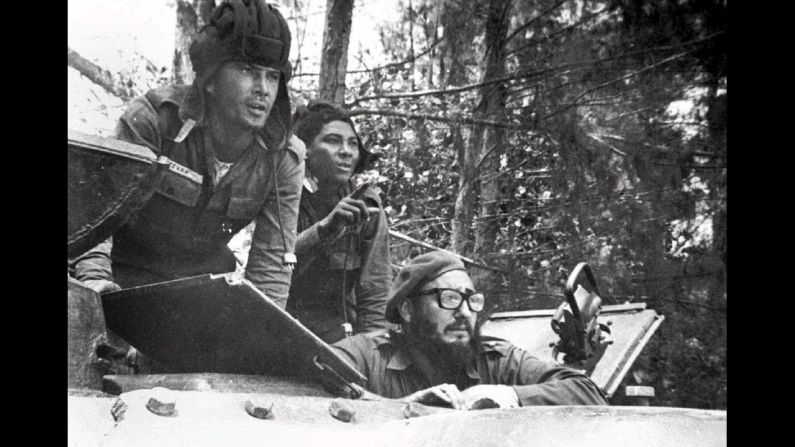

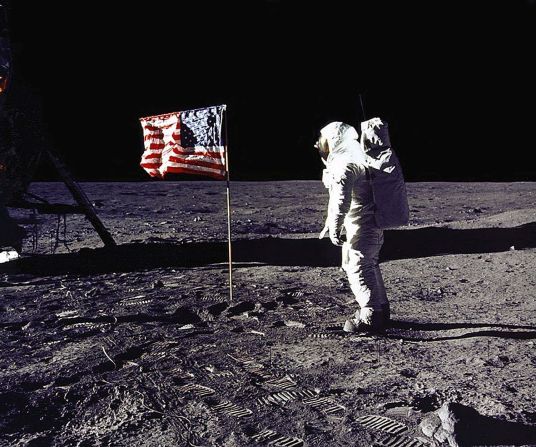

Nixon was elected by a narrow margin. He escalated the war and invaded Cambodia. He appointed Warren Burger as chief justice of the Supreme Court, as well as William Rehnquist, who would serve on the court for the next 33 years. Nixon’s criminality subverted the 1972 presidential election, for which we are still paying a price in national cynicism. American history would have been dramatically different – and far better – if Humphrey had won.

The president who takes office on January 20, 2017 will most likely have at least one Supreme Court vacancy to fill, and probably more. The rights of today’s children – to vote, to control their reproductive lives, to have access to health insurance – will be determined by those justices for decades to come.

We have heard the “Bernie or Bust” slogans of many Sanders supporters, who threaten never to vote for Clinton in the general election. That would be a horrible mistake. The principled opposition to Hubert Humphrey was deeply misguided in 1968, with monumental consequences for the nation and the world. We can only hope that Sanders and his supporters – of all ages – will heed the lesson that we learned so bitterly once Nixon was in the White House.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.

Jim Bendat is the author of “Democracy’s Big Day: The Inauguration of Our President, 1789-2013.” Steve Lubet is the Williams Memorial Professor at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. The opinions expressed in this commentary are theirs.